By Ben Boddez

Jasamine White-Gluz’s love of creepy crawlies inspires a project reflecting the many sounds of nature through a shoegaze lens.

By the beginning of the 1990s, hip-hop had been through a sonic evolution, and early 80s stars like Kurtis Blow and Run-DMC were sounding prehistoric in comparison. These artists’ tracks were seen as more of a chant than a rap, placing heavy emphasis on the last word of every line. When Rakim introduced multisyllabic rhymes, this new style became the norm and the standard for rap going forward.

With Michie Mee and Maestro Fresh Wes breaking through, a lot more seemed possible. The stigma of the watered-down Canadian sound was slowly starting to fade. Access to music grew, and acts began to pop up all across the country. No longer dictated by their proximity to New York, each region had its own scene and its own budding stars.

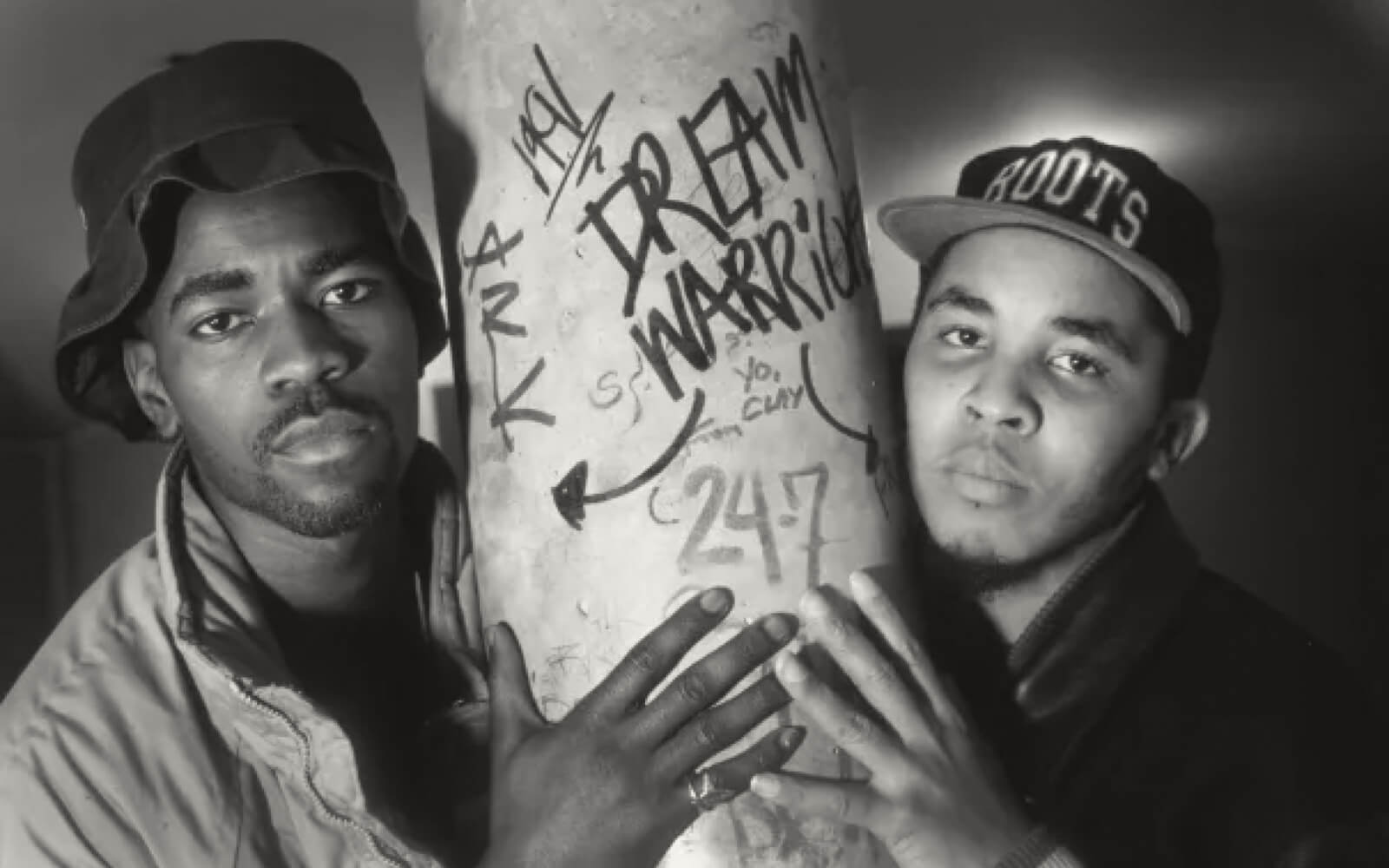

Led by DJ Kemo and Red1, a formidable rap group was formed in Vancouver. Rascalz (pictured above), connected to the core elements of hip-hop’s earliest days, incorporating breakdancing in addition to MCing and DJing.

Rascalz were not the first rap group out of Vancouver, but they quickly became the most popular. Just like many of the acts in Ontario, they had traces of Caribbean influence, which manifested in songs like ‘Dreaded Fist.’

By the time the nineties rolled around, Ron Nelson had moved on to dancehall, and other Canadian platforms had started to include Hip-Hop in their programming. In the era where music videos were actually played on TV, MuchMusic reigned supreme. Getting your video played in a primetime slot was a huge promotion for an artist.

Despite the inclusion of platforms like MuchMusic, the lack of support from labels continued. Before being an independent rapper was the internet’s favourite pastime, signing to a label felt like winning the lottery.

For Rascalz, signing to a label wasn’t as straightforward. Sol Guy was the manager for the group early in their career, and his work in pushing the group independently got him noticed by BMG. He vowed to still work with the group, hoping to get them signed. Kemo remembers signing with BMG feeling like an unlikely move. “I’m sure these label execs would have never considered us, if Sol didn’t present us and praise us,” he says. “He must have sold the shit out of us to get them to give us some kind of deal.”

Beat Factory’s Ivan Berry (Source: discogs.com)

In 1991, the Junos added Best Rap Recording to their list of awards, with Maestro’s Symphony in Effect winning the inaugural prize. The following year, a hip-hop duo from Toronto took home the trophy on their own rise to prominence. The Dream Warriors were the first real international hip-hop success in Canada. Beat Factory’s Ivan Berry managed them, and still does this to this day. He actually met King Lou in the bathroom at a concert.

“I was taking a pee in a urinal and he (Lou) said ‘You’re Ivan Berry!’ and I said ‘Yea’,” he says. Admittedly, he thought that was weird, but he heard him out anyway. Lou preceded “I rap,” and Ivan responded “So buss something for me?” While telling this part of the story, Ivan breaks out laughing.

“I’m peeing, he starts rapping and the shit he was rapping about I remember very clearly,” he says. “It’s on the first album, but it was never a single off Voyage Through the Multiverse. Because Lou was talking about being a…I forgot what they’re called. Like a king, or a kingpin in Dungeons and Dragons.”

This song that Lou rapped for Ivan made its way onto their first album. It wasn’t the only song to talk about this fictional universe. Although they’d be classified as Jazz Rap, the actual content of their music was quite dissimilar to their peers.

It was Ivan’s responsibility to make these obscure and intricate rap songs palatable for the masses. Their first album And The Legacy Begins was a huge success, not only in Canada, but in Europe as well. It won Rap Recording of the Year at the Juno Awards in 1992. The group’s brand of jazz-influenced rap transcended the mainstream, but was still underground in America.

The Dream Warriors (Photo: Getty Images)

Developing its own identity and fandoms, it became clear that Canada had a burgeoning love for lyricism. The lack of commercialism inadvertently placed an emphasis on skill and performance. The Dream Warriors sold like a mainstream act without their sound feeling watered down.

Songs like “Wash Your Face in My Sink” were light sonically, but carried deeper themes. The track goes into detail about feeling that the bathroom is the most intimate room in anyone’s home, a place that should always be kept clean.

“The sink is where you cleanse yourself and the toilet is where you dispose. The whole meaning behind that song is telling negative people they can’t hang with them,” Berry says, taking pride in being able to translate these tunes to the masses. “He’s like you can’t wash your face in my sink, because if you wash your face in my sink, you’re going to dirty my sink.”

The success of Dream Warriors overseas was encouraging, because many consider the 90s a lull for Canadian hip-hop—at least from a commercial standpoint. It wasn’t until “Northern Touch” hit in 1998 that the fire was reignited, the song representing a culmination of many things happening all over the country.

The track’s origins were in talks of a compilation album featuring some of the top hip-hop artists from different labels as a showcase of Canadian talent. One of those songs became “Northern Touch.”

Rascalz’ DJ Kemo produced the track, which was originally made as a demo for Vancouver rapper Jay Swing and featured Red1 and Checkmate. Like so many beautiful things in hip-hop, the track grew and rounded out organically.

“Kardinal was giving Choclair a ride to the studio that day,” Kemo says. “I’m not sure who got Thrust on it, it must have been Big C (Craig Mannix). Kardinal was there at the time, and they let him do the hook, and that’s how the record came about.”

The label was in love with the record and suggested that the Rascalz put it out. The captivating power of the song seemed to be clear immediately, and a video was shot to help push the track.

It was a success in Canada as well as the United States. The first hit Canadian hip-hop song in almost a decade, and the first ever to chart on the Hot 100. This track fit more with the street sound that dominated New York, and gave Canadians a lot of credibility. In previous years when a song sounded Canadian meant it was weak or watered down. Northern Touch loudly rebuked that claim.

By Ben Boddez

Jasamine White-Gluz’s love of creepy crawlies inspires a project reflecting the many sounds of nature through a shoegaze lens.

By Cam Delisle

The Calgary-born pop powerhouse brought her high-voltage Miss Possessive Tour to Rogers Arena for two consecutive sold-out shows.

By Hannah Harlacher

The Montreal songwriter on breaking up with the industry, choosing process over product, and building a creative life on her own terms.