A Different Man Provides Darkly Comic Exploration of Beauty and Identity

Writer-director Aaron Schimberg masterfully dissects society's fixation on physical appearance by inverting the tenets of body horror.

Directed by Aaron Schimberg

by Prabhjot Bains

- Published on

How much of who we are is tied to our physical form? Aaron Schimberg’s A Different Man confronts an oft-asked question with wry, pitch-black earnestness. While the conclusion it reaches is nothing revelatory, it’s answered with such flair and chutzpah it might as well be. Shimberg’s body-horror inversion breaks new ground for filmic representation, with its odd story of physical transformation boldly subverting Hollywood’s typical depiction and treatment of people with facial differences. Yet, it also places audiences in its crosshairs, weaponizing their preconceived notions and expectations while making them laugh and wince in equal measure.

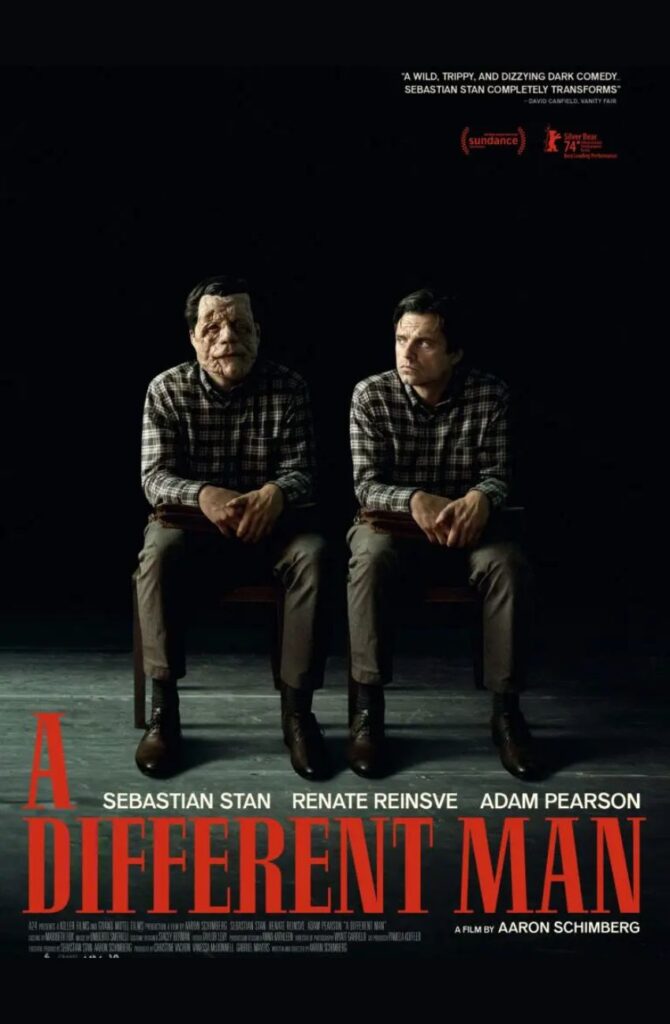

Buried under heavy prosthetics, the ever-handsome Sebastian Stan stars as Edward, a jumpy and shy individual who feels defined by his apparent facial differences. It’s a casting choice that initially raises eyebrows, especially as Edward undergoes experimental treatment and is reborn as an Adonis. But it’s all part of Shimberg’s grand design, to craft a holistic piece of exploitation that both critiques itself and the filmmaking tradition it’s a part of. It all reaches a tipping point when A Different Man introduces Oswald, played by Adam Pearson, an actor with actual facial differences due to a real-life condition called Neurofibromatosis.

Unlike Edward, Oswald is the centre of attention despite his unconventional appearance. He’s outgoing, pleasant, and unbelievably likable— representing everything Edward couldn’t dream of being before or even after his physical transformation on screen. The epitome of effortless charm, Pearson lights up in a deceptively simple performance, simply because he’s afforded the space others like him were denied. He serves as a riveting foil to Stan, who in a career-best turn, lends nuance to a soul that is slowly revealed to be devoid of it. It’s a performance that stands in stark, daring contrast to Stan’s earlier work, laying everything bare to capture a man who becomes more pathetic and disturbing as he’s made more traditionally beautiful.

From the vividly textured film grain to the neo-noirish jazz score, A Different Man feels finely plucked from the paranoid oeuvre of ’70s American cinema. It stands as an immersive and darkly comic thriller that forces us down an increasingly uncomfortable rabbit hole with panache. It offers a two-way mirror, illuminating the hypocrisies of its genre and the expectations of its audience. In cleverly picking apart the tenets of identity and performance, A Different Man manifests as a rare piece of body horror more concerned with the mind and soul.