A Listener's Perspective on Spotify

Tara Monfaredi on ditching her Spotify subscription in favour of sustainable, artist-first alternatives.

by Tara Monfaredi

- Published on

I grew up burning mixed CDs on my family computer, buying them from Fantastic Flea Market in the basement of Dixie Outlet Mall and from HMV. I played them on my budget Walkman, a reliable CD player in my bedroom, or using Windows Media Player on our PC. I collected vinyl records from garage sales, local concerts, and record shops over the years. I’m also of the generation of MP3 players and iPods, watching them go from holding less than 100 songs to 20,000 songs, then watching them fall out of fashion.

Tara Monfaredi

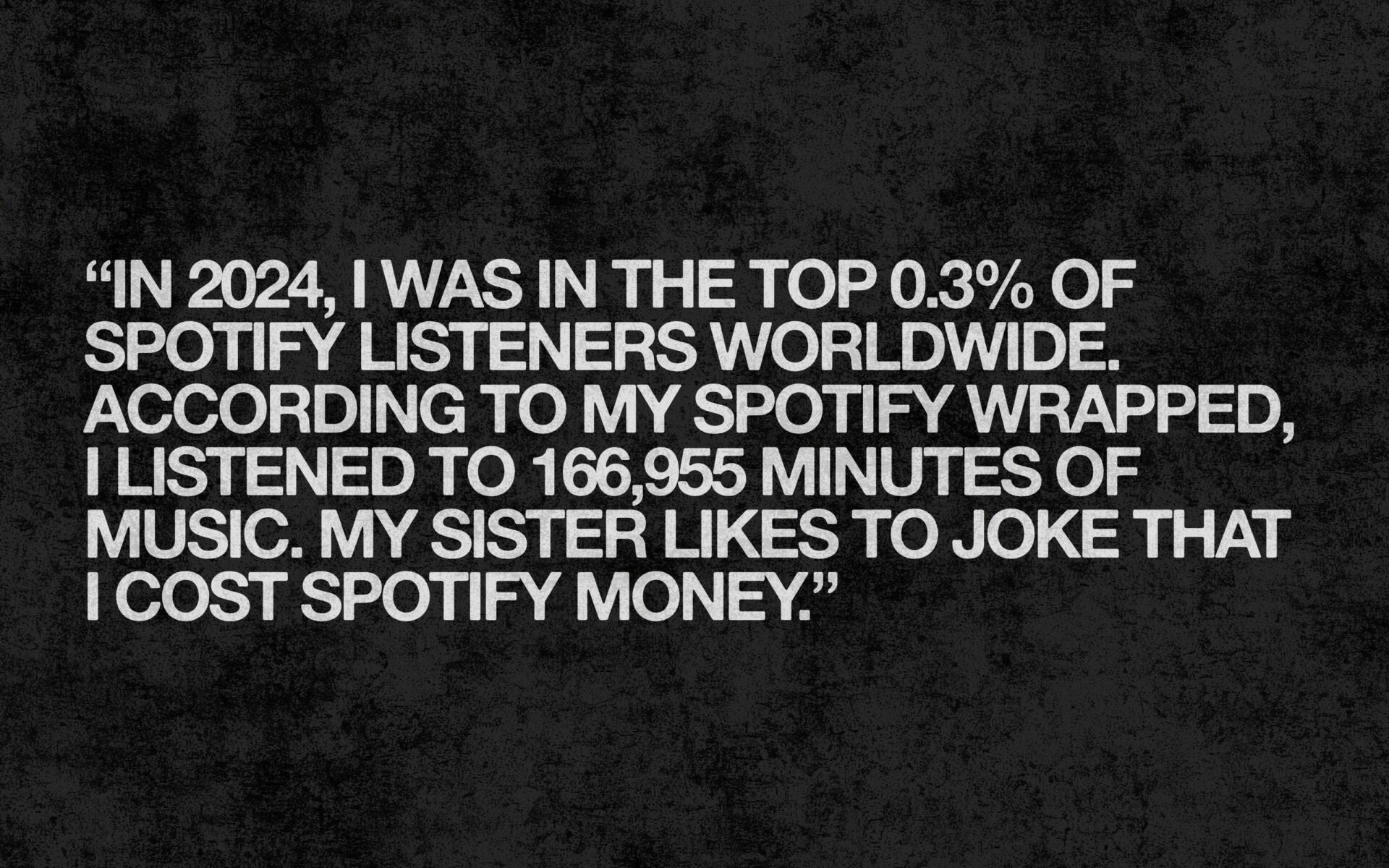

In 2024, I was in the top 0.3% of Spotify listeners worldwide. According to my Spotify Wrapped, I listened to 166,955 minutes of music—thousands of songs and albums across countless genres amassed over 15 years in a huge digital library. My sister likes to joke that I cost Spotify money.

In 2008, when Spotify launched to combat piracy, I was in Grade 10, half my lifetime ago. I downloaded the app and have regrettably been using it since—until recently, when I finally got the push I needed to delete my account and the app for good. Earlier this year, I learned that Spotify invested billions of dollars into AI military drones. I had long wanted to decenter the music streaming platform because of its exploitative treatment of musicians, namely its refusal to pay them fairly, or at all.

Gothic singer-songwriter Zola Jesus has been vocal about her anti-Spotify stance in the past, in light of AI songs taking over the app, and some artists, like Montreal powerviolence band Jetsam and indie darling Joanna Newsom, have never had their songs on the platform. Kitchener hardcore punk band Bad Egg pulled their songs off Spotify, along with many others, after news of the military investment earlier this year.

Streaming has never been in the best interest of musicians. Then, on April 1, 2024, they stopped paying royalties for songs with fewer than 1,000 streams. The joke was on the mainstream music industry and its forgotten days of just compensation from physical media sales and live shows, of artists being afforded careers as working musicians, and of record labels investing in artists to develop their crafts and careers. Labels screwed a lot of people over too, but the point is, the mainstream music industry has had the body odor of decay for decades, and one reason for that is streaming. (Along with Ticketmaster and Live Nation, but that’s for another op-ed.)

In my pursuit to ditch Spotify, I discovered Resonate, a community-owned service in development that’s governed and owned by its artists, members, and workers—a music streaming cooperative. Their platform will use an innovative pay-as-you-play, stream-to-own system that allows you to own a track after $1.40 paid in listens, or after you listen to a song about nine times.

Their catalogue comprises deeply obscure artists; I’ve heard of none of them, which can be great for discovering new underground musicians, but not so great when you’re in the mood to hear the same songs you’ve been listening to for the last 12 years. I would say it’s for fans of the more obscure side of SoundCloud and Bandcamp, unless the service really takes off and more well-known artists join.

The model that Resonate uses is a progressive way forward for music streaming—a future for music streaming that isn’t deeply inequitable. In the meantime, they’ve paused new sign-ups to work on their system.

The absolute best way to buy music is by doing so directly from the artist, at their show or on their website or store. Buying a CD, vinyl record, or cassette at a merch table or local record store will always be more lucrative for the bands we love than streams.

I champion physical media, but in our on-the-go, digital world, I need a way to listen to music on my phone, and I landed on buying digital media on Bandcamp for daily listening. It’s a close second to buying physical media in terms of putting money directly in artists’ pockets, especially if you make your purchases on Bandcamp Fridays, when they waive the 10–20% fees they typically take.

There’s no subscription fee for users. I buy a digital album once for $5–$15 on average and then own it. This act alone is a much more mindful practice. It’s the difference between hitting the heart button on every song you find mildly catchy and buying a whole album because you’re moved to do so (and because you’ve played your current comfort album three times already and Bandcamp won’t let you listen to it again without “opening your heart/wallet”). You can also purchase individual songs; however, I have yet to try that. In this way, Bandcamp encourages me to listen to a full album, front to back, instead of always shuffling a playlist. Listening to music this way has been a more mindful practice for me as well—a less passive act—and allows me to enjoy the work how it was originally intended to be heard.

Although Bandcamp seems to be the best option for musicians, they also effectively shut down their workers’ union at the end of 2023. Bandcamp was sold to Songtradr, which fired half its workforce, including two-thirds of the union-eligible engineering team and every member of the union’s bargaining committee. The union filed a complaint and is considering a second unfair labour practice charge while they strategize next steps.

I am extremely pro-union and working class. Bandcamp workers are not striking and have not called for a boycott. This is something you’ll have to grapple with, as I did, if you go this route. There is no streaming platform currently that will pay artists what buying digital media will pay, and other tech-giant music platforms, from Apple to Tidal, are the same. Apple has its own atrocious labour practice violations, and Tidal faced a class-action lawsuit for allegedly underpaying artists and using false numbers to calculate payouts. So, do with that what you will.

Canceling my Spotify subscription allowed me to appreciate and reconnect with music in new and familiar ways; to seek out more physical media and a way to pay for the music I listen to beyond a minuscule subscription fee; and to contribute to the music communities that I love more directly.

At the moment, if I’m not listening to CDs (I’ve picked up a couple of good ones at the thrift store recently), I’m listening to the ten albums I have so far on Bandcamp until I carefully choose another LP to add into rotation. I’ve been enjoying building my digital music library back up, slowly, from scratch. Some people have chosen to move everything over from Spotify to a new platform—that’s possible and works for them. I wanted to break up with music streaming entirely and didn’t mind starting over.

I believe it’s all a process, a journey, and on this journey, I’m making a habit of checking my record store purchases for digital download codes.

By Cam Delisle

Look to the (pop)stars for thoughtful insight into your month ahead.

By Wrené Nova

Wrené Nova on surviving the streaming grind, reclaiming her art, and why the industry is failing artists everywhere.