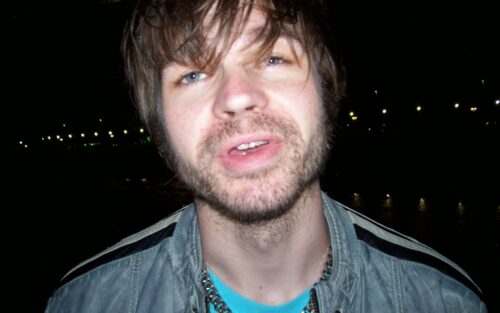

For Ben Arsenault It’s All In Picking The Line

On his sophomore album Make Way For This Heartache, the country music artist is finding peace of mind with hard feelings.

By David Gariepy

Photo by Emile Benjamin

- Published on

Reminiscent of the “classic era” of country, Arsenault approached this album by picking a line – taking an idea [that] you centre everything around,” inserting a small “kind of personal relevance” and also writing to broader relatability. This creative process follows a long tradition in country music of wrapping one’s own voice around someone else’s story, expressing its truth.

While the better part of the last decade saw Arsenault playing with psychedelic alt-country outfit Real Ponchos, he has long been drawn to the “more traditional approach” of the genre, simultaneously recording solo demos and a debut album. Inspired by Bob Dylan’s scores of bootlegs and alternate takes, Arsenault has also reworked many songs like “Flowers At Your Feet” from earlier releases until he felt he “arrived at something special.”

Writing this album was as much about the music he was listening to as the company he kept. A deep dive into Wynn Stewart, Buck Owens and Gary Stewart – plus spending time with Etienne Tremblay (Janky Bungag, Moonlight Years) – produced early versions of “Grand Forks” and “Too Late,” while “Basement Blues” was deeply inspired by Austin artist Leo Rondo, who Arsenault met on a trip down south. With fifteen featured performers, the new album honours both past and ongoing friendships, as well as musical partnerships including Aiden Ayers, who produced and played on Arsenault’s first self-titled LP, Real Ponchos’ drummer Emlyn Scherk, and Austin-based pedal steel guitar player Caleb Melo.

A prominent part of this musical family is the North Country Collective (NCC), a promotional country and Americana music collective and record label based in Vancouver, with whom Arsenault released his new album. When asked why it felt right to partner with the NCC, Arsenault speaks to the label’s tight-knit group of roots musicians. “We’ve all been doing the same thing for so long; we’re just on the same page,” he says.

Arsenault’s familial connection to country music shows how deep his roots go. “Arsenault” is an Acadian name, belonging to a people with a long history of farming and fishing the east coast of Canada. Asked how this history parallels country music, he replies, “Maybe it’s just an appreciation for the ‘basics of love,’ as Waylon Jennings says, or like, a sensibility,” one that’s been passed on generationally. Lyle Lovett, Neil Young and Lucinda Williams were common listening in the Arsenault household. He recalls his dad singing Hank Williams songs on weekends while making breakfast and on family hikes “to make noise for the bears,” and his grandfather amassed a large collection of old country music records that Arsenault had the privilege of listening to growing up. As a nod to his heritage, Arsenault dons his grandfather’s hat on the album’s vinyl sleeve and in the video for “Never Been The Boss.”

As his life and music continue to evolve, newly-penned tracks like “Never Been The Boss” and “I’m Changing Too” reflect a more current headspace for Arsenault. Whereas songs written earlier on the album pointed to “heartbreak, and singing about life and disappointment as a way to find ease and growth,” these new tunes reflect “being more settled, knowing who I am, [and] where I fit into the bigger picture.” He is now married and a new father. Arsenault maintains core elements of country music, which he says has “uplifting musicianship, and a shuffle or beat you can dance to.” But this album also explores other sensibilities – hinting at a conscientiousness about the cosmic aspects of reality, as he sings on Grand Forks: “In this life, nothing is as it seems.”

In his late twenties, Arsenault began cultivating a meditation practice within the Zen Buddhism tradition after suffering a significant head injury as a result of a bike accident. “Zen was a really big refuge,” he says about that time, adding, “it gave me some kind of focus to my life.” In a genre where partying and hard living often go hand-in-hand with sombre reflection, Arsenault’s experience was grounding, helping him realize there were some areas of his life he had to take responsibility for. Arsenault reflects that while “Zen Buddhism and country music are not typically associated […], they actually complement each other well.”

As taught in the Maka Hannya Haramita Shingyo (a Buddhist sutra referenced in Arsenault’s work), suffering is a universal constant we share with everyone. Similarly, country music has a long history of exploring themes of pain, suffering and loneliness – to bring them out of the personal and into the collective consciousness, showing us that we are not alone, but connected on a human level. Like the best country music, Arsenault’s work meditates on personal strain as something to be suffered through as a bridge to peace, or “broken heart to peace of mind,” as he sings. When asked if his album could be distilled to a single piece of wisdom, his reply is consistent with what he has been saying all along:

“If you make way for this heartache, kind of accept it, be present with it, the world’s going to open up a little more for you.”

Fittingly, when asked what he would like people to know about him he says, “Ideally, I’d like people to come to their own conclusions about who I am through my songs… even better, they’ll discover something about themselves in the songs too.”

Next up, Arsenault plans to get back on the road. On Sept. 7, he’ll be playing in Vancouver at The Heatley in a shared set with Etienne Tremblay. “It’s a good opportunity to play the album again with Etienne because he was there when a lot of these songs were written,” he says. He also has a show at Wheelies in Victoria on October 19, with plans to tour in Florida, Nashville and Austin.

By Stephan Boissonneault

Nate Amos revisits a decade of stray ideas and turns them into his most compelling record yet.

By Khagan Aslanov

Mike Wallace’s electro-punk project premieres the hypnotic, percussion-driven video for "Certain Days."