By Prabhjot Bains

Drawing from personal experiences, the Oscar-winning animator crafts an emotional narrative that pairs outlandish humour with profound sadness.

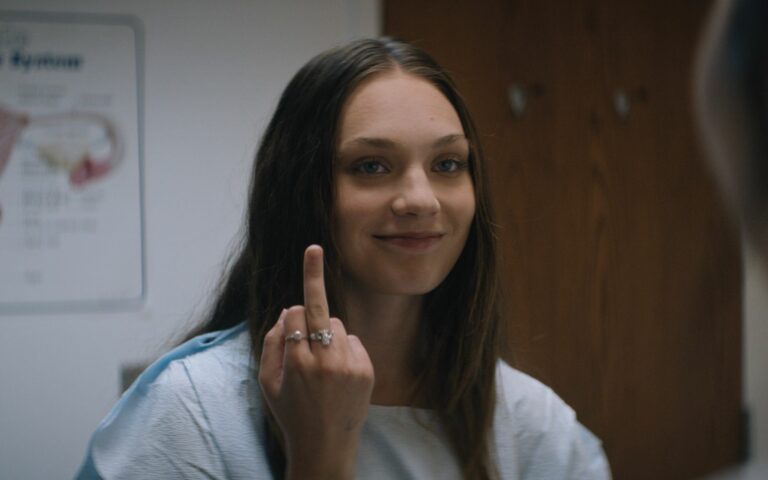

“The body is not a thing, but a situation.” Fitting In opens with this quote from French philosopher Simon de Beauvoir, setting the tone for the movie, in which 16-year-old Lindy (Maddie Ziegler) finds out she is missing a uterus and part of her vagina as she becomes sexually active. This condition, called MRKH syndrome, is often discovered in adolescence as individuals realize they lack a period when they should get one.

Awarded VIFF’s Best Canadian Film of 2023, Fitting In is the autobiographical account of director Molly McGlynn, who was herself diagnosed with MRKH syndrome at 16 years old. It takes the form of a coming of age story, where adults encourage a teenage girl’s vaginal growth and the use of dilators, in order to accommodate heterosexual intercourse. Failing this quest, she will learn to grow in other ways.

McGlynn reveals the thought process behind casting Ziegler, The child prodigy dancer often associated with Sia in the mid 2010s. “She had this gravitas about her and she was a dancer,” she says. “Her ability to express emotion through her body and eyes was perfect for this role, because there is so much she cannot say.” For a film that delves so much into body politics, casting a dancer seems fitting.

Writer/director Molly McGlynn

Fitting In also sets out to deconstruct the medical and social taboo around MRKH syndrome. “I think the medical system can look at the bodies as an isolated thing, unconnected to a whole person,” says McGlynn, underlining doctors’ lack of interpersonal skills. Yet, the medical field dictates how bodies should be and what their purposes are. Lindy is a teenager, a runner, a person exploring her sexuality, but she is reduced to her reproductive (in)capacity and (in)ability to be penetrated. Her body cannot just be her body, it comes to represent her political and social situation as a woman in society–and the expectations of joining with a man with a penis and having babies. But where does she fit, if nothing fits inside of her?

McGlynn discusses her ironic use of Aqua’s “Barbie Girl,” a choice that, she insists, preceded the announcement of the eponymous film by Greta Gerwig. Unlike the box office hit, which displayed surface-level feminism, Fitting In expresses a political stance on the medical objectification of the female body. McGlynn explains, “To me, putting this song is about the lyrics like ‘made in plastic’ and the sort of packaged femininity. When I’m in the darkest moments of my life, I find the most absurd humour. So for me it’s like, ‘What is the worst song that they could play during the MRI?’” Fitting In doesn’t want women to stop being dolls (or to sell them to us), it shows that they never were dolls to begin with.

In the soundtrack, McGlynn also pays homage to feminist punk bands Mannequin Pussy and Peaches, who excel in smashing the feminine shackles. She continues, “I use a punk song during one of the dilating sequences because… I want female rage! I was so angry as a teenager. I didn’t necessarily want a sad indie song over that. I wanted her to punch a fucking wall.” Little by little, Lindy learns to stop listening to societal authorities and norms.

(L-R) Emily Hampshire stars as RIta alongside Maddie Ziegler (Lindy) in Molly McGlynn’s Fitting In.

In order to decentre heterosexuality, McGlynn gives the protagonist a non-binary love interest. More than being an effort of queer representation, this narrative choice allows Lindy to envision her sexuality differently. “In the whole diagnosis of it, there was a presumption that you want to have heterosexual penetrative sex,” McGlynn says of her own experiences. “Having the character explore that in the film was also my way of acknowledging that not all people with MRKH are heterosexual.” McGlynn prefers to leave Lindy out of sexuality and gender labels, as she considers her to be in a phase of exploration of her identity, an important and sometimes scary moment of life.

Fitting In is loaded with teen horror references, from Ginger Snaps to Carrie, and of course the iconic Jennifer’s Body, which the high school set design and eerie lighting emulate at times. “I think there’s a version of Fitting In that is a high concept body horror movie,” McGlynn candidly remarks. “There’s something funny to me because this condition is discovered usually when you don’t get your period, and the irony [is that] the absence of blood [is] the horror.” Adolescence is horrifying. “Hell is a teenage girl,” even. Hell is learning your body does not belong to you. But hell, most of all, is a doctor prescribing you a dildo at 16.

Fitting In is playing in select theatres across Canada on February 2.

By Prabhjot Bains

Drawing from personal experiences, the Oscar-winning animator crafts an emotional narrative that pairs outlandish humour with profound sadness.

By Ben Boddez

A satirical spin on a classic tale, actor Jason Sakaki talks about depicting Vancouver’s metalhead mayor and the spirit of this annual tradition.

By Liam Dawe

The annual music industry gathering is setting the stage for career-defining connections beyond the prairies.