The Exquisite Melodrama Of Guy Maddin

In conversation with the legendary Canadian auteur about his creative process, psychological plausibility, and those dreamy little states of honesty.

by Maggie McPhee

- Published on

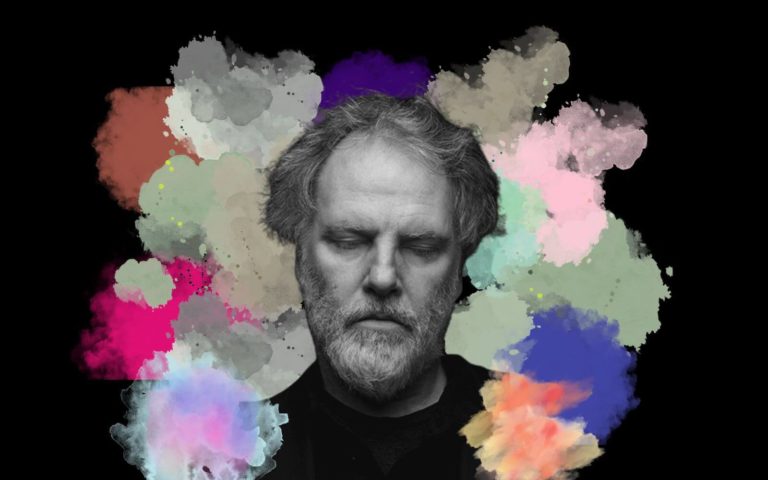

Chatting with filmmaker Guy Maddin is like sitting around a campfire at night. It’s brilliant, warm, flickering with mischief and the potential for chaos; a comfort to the primordial soul. Maddin even looks the part rendered on the Zoom interface: a shock of white hair and bright eyes dramatically outlined by a dark wall and black turtleneck. But this fire has been ablaze for more than 100 years, since the dawn of cinema itself. It has witnessed and absorbed the silent era, the early talkies, Russian constructivism, melodrama, surrealism, the avant-garde, and it has reconstructed an entire history in flashes of dazzling, raw energy. Maddin’s movies burst at the seams with cinematic allusions and illusions. They purloin from the old—intertitles, iris shots, gauzy lenses, colour tinting—to construct collages of pure emotion, vivid celluloid sensoriums.

Maddin, 66, Canadian art auteur par excellence, invokes the campfire when explaining his love for silent movies, the primitive style he calls “one giant step closer to fairytales.” He cites the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, and even more ancient texts like the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Old Testament. “They’ve remained so durable over the centuries because there’s psychological plausibility in even the most bizarre plots,” he says. “These stories which have been burnished by countless retellings around campfires and at bedtime storytime have survived the millennia for a reason. They’re getting at something that’s inside all of us.”

The Forbidden Room | Canada 2015 | Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson

Many of Maddin’s films take up that mantle. They dive headfirst into the bizarre, brutal, and murky underbelly of the human subconscious in search of something universal and eternal. To excavate the deepest parts of himself, Maddin regularly pulls directly from his dream diaries, attempting to reinscribe them for the screen. His first short, “The Dead Father” (1985) arose from the staggering process of grieving his father at the age of 21. “All the emotional circuit breakers blew without realizing it,” he says. “My subconscious decided to grieve on the instalment plan by revisiting him every night in dreams.”

Using literary devices inspired by Nabokov, Dostoevsky and Kafka—writers who crafted oneiric feeling-states better than any film seemed to manage—Maddin approaches his scripts as if writing a book, in the hopes of discovering those same “dreamy little states of honesty.” These early experiences moulded Maddin’s creative process and working method for the decades to come. “I take a feeling that matters to me, like grief that is sometimes too intense to bear, but then it’s replaced by a near narcotic belief that there’s nothing to grieve over, replaced by disappointment, and then repeat in an endless cycle until you finally get tired of dreaming of that and you finally grow to accept that someone’s gone.”

His quest for emotional honesty is paradoxically balanced by an obsession with mythology. Growing up in Winnipeg, Manitoba in the 1960s, relying on “weak antenna television signals to bring you America,” Maddin mentions that “it always seemed like even though the reception was snowy, the message was strong.” Whereas the crystal-clear Canadian television never struck Maddin with the same awe. “The secondary goal of mine was to commit to film emulsion—the mythologizing medium of the 20th century—the small things around me in my Canadian everyday with the hope that Canada, my Canada, my Winnipeg, my Gimli, would be mythologized someday by this accumulation of film.”

His first feature-length film, Tales from the Gimli Hospital (1988) was a foray into myth-making from the not-so-humble perspective of a humble Canadian. To make Gimli, Maddin converted his aunt’s old beauty parlour into a film studio and shot many scenes in his own home. Without money to pay actors to memorize scripts, he recorded all the dialogue in post-production and thus birthed one of his signatures—comically bad dubbing. The cumulative effect is a mad-dash cult classic that was simultaneously rejected by TIFF and screened for an entire year in Greenwich Village.

Whether chasing myth, memory, or meaning—or all three—Maddin never shies away from the melodramatic. “A lot of people think of melodrama and of dreams as exaggerations, distortions of the truth, but actually, they’re just the disinhibition of the truth, they’re making truth more visible for viewers. I actually think melodrama can be very psychologically honest art,” he says. Melodrama permits Maddin to disavow social decorum and embrace impulse, id, and libido. It brings him closer to the fairytale.

“I actually think melodrama can be very psychologically honest art”

Maddin’s movies contain the most “movie.” His limitations venturing out as a DIY, no-budget filmmaker in a dreary town with scarce film resources actually created the conditions for a visionary to submerge so deeply into cinema that he’d come out on the other side to a space no filmmaker had yet to go. His films overspill beyond the borders of genre. They privilege oft-neglected cinematic elements—costume, sound, lighting—with as much reverence as plot. His working definition of expressionism enlists these other elements to reflect someone’s psychology in every inch of every frame. “Everything a viewer sees in the set dressing, the landscape, the decor, hears in the music, the sound mix, in the style of dialogue is an outward projection of what’s going on in the main character’s state of mind or in the director’s state of mind. It’s not just a bunch of gratuitous art design” he says.

Tales from the Gimli Hospital Redux | Canada 1988 | Guy Maddin

Music is one such element dear to Maddin’s heart. The Forbidden Room (2015), a fantastical multi-narrative film, contains 118 minutes of music, “sampled, chewed up, and regurgitated” across the entire running time. Once again, financial constraints induced paroxysms of creativity. Early in his career, unable to pay for rights to music, Maddin worked with scratchy 78 RPM public domain records, and for an extra layer of legal security would play them backwards, cut them up, slow them down, or otherwise distort them beyond recognition.

As an underground filmmaker, Maddin is well loved by underground musicians. His 2006 silent film Brand Upon the Brain! toured with an orchestra and screened with live narration performed in some instances by Lou Reed or TV on the Radio’s Tunde Adebimpe. Sparklehorse, also a fan, commissioned Maddin to make a short-film for their single, “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

Maddin’s oeuvre overspills the borders of medium, too, working on music videos, installation art, books, and experimental film. But his entrenchment in the art world hasn’t dampened his sense of play. All told, his catalog of 12 features and 63 shorts are like brands on the brain. They immerse viewers in intense dreamscapes where the line between film and reality can no longer be discerned. “I want people to encounter my work and have a response,” he says of his goals as an artist. “Preferably laugh, but if they have some other reaction, like a headache that won’t go away, I’ll settle for that.”

***

Vancouver’s Cinematheque has put together a major Guy Maddin retrospective — the largest they’ve done to date —over eight weeks starting January 26. Maddin will be in conversation opening night to celebrate the newly restored and “redux”-ed Gimli and will return the following evening to present the film he programmed for the series, Tod Browning’s Devil Doll (1936) | TICKETS & INFO

By Glenn Alderson

A deep-listening session reveals how Apple Music’s sonic innovation reshapes the way we hear.

By Cam Delisle

Dominic Weintraub and Hugo Williams take audiences on a treadmill-fueled ride through the chaos and hope of modern life.