By Ben Boddez

Composer Jeff Morrow and songwriter Ben Folds speak on the legacy of Peanuts music and why it’s not your average kids’ program.

Werewolves, vampires, aliens, and even the famed slasher are a few of the monsters that have come to define our relationship with cinematic horror. These classic creatures defy all logic and reason, tapping into our deepest and most primal fears. But what if the very battle between logic, faith, and reason becomes the scariest thing of all? In Scott Beck and Bryan Woods’ Heretic, the monsters are put to bed for a terrifying peer into the psyche, and our contentious relationship with religious ideology.

When two Mormon missionaries, Sister Barnes (Sophie Thatcher) and Sister Paxton (Chloe East), visit the seemingly cozy home of the very British Mr. Reed (Hugh Grant) in an attempt to convert him, what begins as a harmless conversation quickly turns sinister. The two not only find themselves locked in the house alone with their host, but also in an ideological game, where their faith is increasingly tested in progressively dangerous and horrifying ways. As the two delve deeper into the household — and in turn, the fabric of their religious convictions — Heretic unlocks what Mr. Reed dubs “The fear of belief and disbelief.”

For the directing duo, that horror of the unknown led them to write and ultimately direct Heretic. After co-penning their fair share of monster flicks, like the breakout hit A Quiet Place and the Stephen King adaptation, The Boogeyman, the directors aimed for something completely different, and far more personal and philosophical. During TIFF, Woods tells RANGE at the Intercontinental Hotel that they wanted to “do a horror film that doesn’t rely on obvious subgenres, [or] on familiar visual gags to get a scare out of the audience.” “We got excited about the challenge of making a suspenseful movie [rooted] in dialogue and ideas,” he says. “If we can make the ideas terrifying and compelling, that’ll age a little better. Horror movies don’t always have a long shelf life. Eventually, you can see the seams on the monster suit as the movie gets older, the effects can fall away.”

The attempt to get cerebral and dig deep into these hot-button, ideological topics is what serves as the directors’ driving engine. Yet, at the same time, Heretic is also a response to their own relationships with religion and faith. Beck says “The movie really is a culmination of the both of us growing up in Christianity and then expanding those horizons as soon as we both married people of different belief systems. We started culminating friends of different beliefs, including a lot of atheists and agnostics.” The two began “exploring all the spectrums of belief and disbelief, [and] finding enriching ways to see how that has affected the world in both good and bad.” That introspective journey, in tandem with what they call the “existential, scary quandary of what happens after we die” led to an excitement for them to share their own neuroses.

Yet, for Heretic to ooze staying power, they needed to give credence to both sides of the debate. Woods believes that “as artists and as writers, our job is to have empathy.” The two tell RANGE that they have a friend who is a Scientologist, and that “it might be easy to [label] it as a cult, but as empathetic human beings we find it interesting to ask what it is about the faith they respond to.”

“We’re up for that conversation, especially since we live in such a divisive, angry world,” Woods says. “We love the idea of having an open conversation about these scary, dangerous things that are so important to people.”

Beck and Woods’ personal feelings run a wide spectrum and don’t feel that one perspective was necessarily correct. “It’s not a movie that makes a statement, it’s not playing to one audience like a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Beck notes. “It’s the beginning of a conversation… and it’s something you can use to reflect upon your own beliefs and how you get to that point.” “To us, that’s always the most exciting part of the movies we love and adore.” Woods adds. “When we’re able to have a long-standing relationship and conversation with it.”

Despite its brainy horrors, Heretic is a talky chamber piece at its core that, at times, can threaten to bore. “That was our biggest fear,” Beck says. “This movie that is 120 pages of mostly dialogue could so easily feel stagnant, so we focused on evolving the language of the camera, the sound design, and also the production design, so we could have all these layered nooks and crannies that evoke an unease and discomfort.” In employing cinematographer Chung-Hoon Chung, a frequent collaborator of the virtuosic Park Chan-Wook (Oldboy, The Handmaiden), Heretic becomes awash with “bold and unexpected swings.” Beck notes Chung “comes from a lineage of shooting movies that aren’t necessarily traditional,” often isolating figures for minutes at a time to foster a subtle yet overwhelming sense of anxiety.

However, Heretic’s grotesque wonders uniformly lie with Hugh Grant’s devilish and delectable performance. His turn is so synonymous with the most palpable and provocative aspects of the film, it’s virtually impossible to imagine any of it being nearly as memorable or riveting without him. “This was one of those scripts that floated around town, and a lot of stars started raising their hands wanting to play Mr. Reed, and we were getting starstruck,” says Beck. “But we had to take a step back and ask: who is the best person to play this role?”

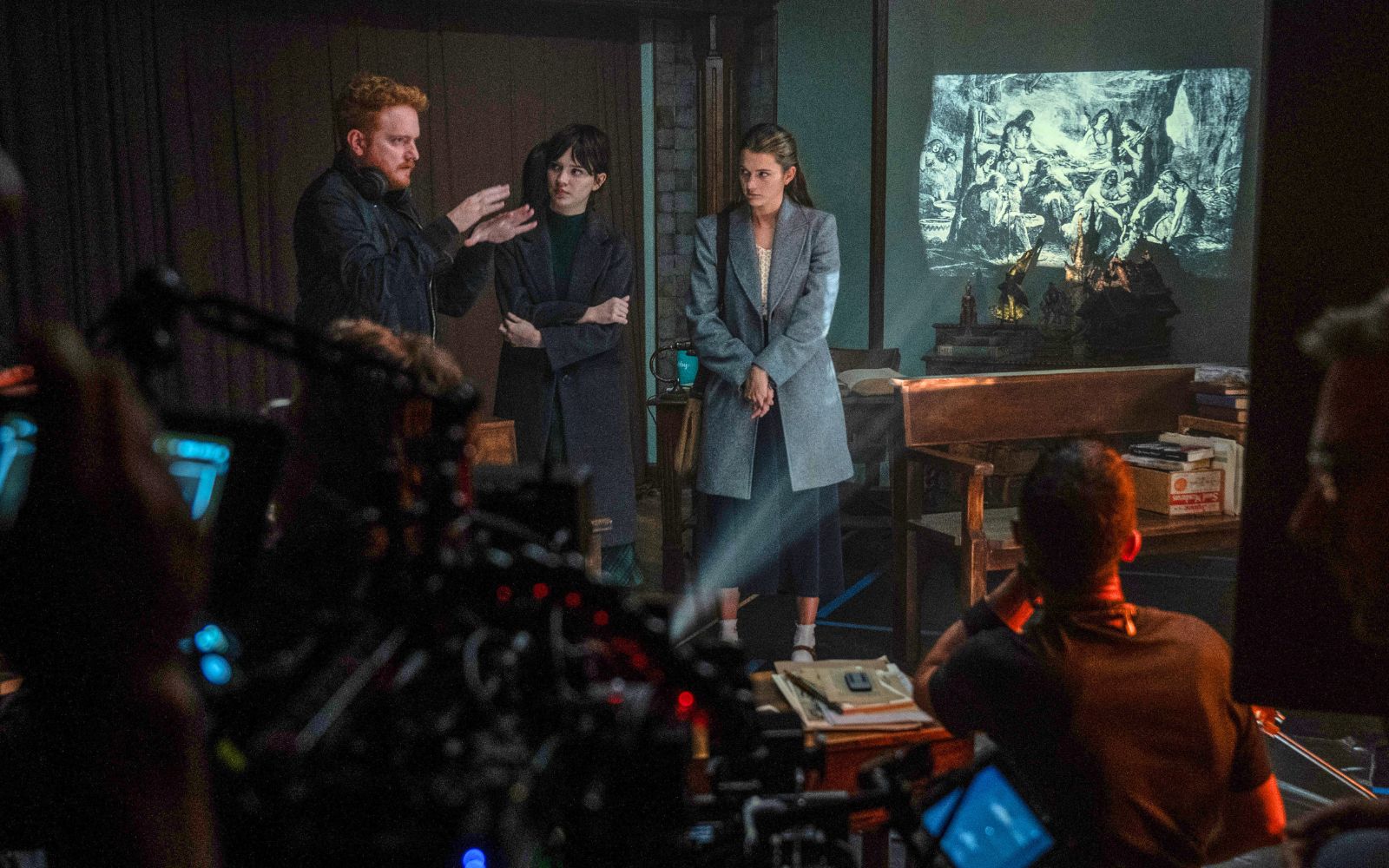

Filmmaker Bryan Woods on the set of Heretic with Sophie Thatcher (Sister Barnes) and Chloe East (Sister Paxton).

Woods says, “You need an actor who can disarm the audience and get them swept up in this crazy experience, and we kept coming back to Hugh.” “In real life, he’s as meticulous as Mr. Reed is on screen, investigating and pressure-testing every piece of the material,” Beck continues. “We joked with A24 about publishing a book of all his notes, because he’s scrutinizing every single word to live and breathe as Mr. Reed.” That sense of commitment, along with “the allure of weaponizing 30 years of goodwill with the audience from his romantic comedy days,” fostered a beautiful nightmare of a performance.

Beck and Woods loved filming Heretic in Vancouver. “If we could make every movie in Canada, we would,” says Beck. “Everybody on the crew, from dolly cribs to scenic painters, we were so impressed by the level of artistry.” “The kindness and the spirit of this country is amazing,” Woods adds. Perhaps it’s that rich and generous foundation that allowed the two directors to craft a wonderfully twisted horror of ideas.

Heretic is in theatres on November 8

By Ben Boddez

Composer Jeff Morrow and songwriter Ben Folds speak on the legacy of Peanuts music and why it’s not your average kids’ program.

By Alexia Bréard-Anderson

Montréal’s premier gathering for electronic music and digital creativity returns with an immersive three-act program bridging AI, XR, Indigenous tech, and ecological imagination.

By Adriel Smiley

Ian Mark Kimanje’s powerful documentary traces Carnival’s roots from slavery and survival to global celebration.