By Stephan Boissonneault

With There Is Nothing In The Dark That Isn’t There In The Light, the veteran vocalist leans into intimate, searching folk.

We caught up with Crighton to dig into the origins of her unique musical path, the collaborators who helped shape Death & The Fool, and the family stories woven through the record.

How did your relationship with the harp—and music-making in general—begin?

I started with singing, from a young age, in a children’s choir out of the University of Alberta. When we moved to Duncan on Vancouver Island, there weren’t as many resources. I did some performances, but nothing like what I’d done in Edmonton. I began writing my own songs and took private singing lessons. I wanted an instrument to accompany myself, but I wasn’t drawn to guitar or piano.

One of the best stories is when my mom took me to see Loreena McKennitt in Duncan when I was about nine or 10. The joke is I either slept through the concert or went into a trance, then said, “I want to play the harp.” It was pre-internet, so it wasn’t easy to find a harp or teacher, but my parents figured it out.

I started with a classical teacher, then a Baha’i woman who wrote her own songs and encouraged me to do the same. Pretty much as soon as I got the harp, I started writing. I was that kid always singing made-up songs.

Were your parents musical?

They worked in theatre, so not musicians per se, but music was part of my upbringing. I went to a Waldorf school, where music is woven into the education. I played cello, recorders, and sang in choirs. One of my songs, “Greenblade,” is tied to dancing around a maypole at school. I’ve always felt more like a storyteller than a musician—I use music, art, and film to tell stories.

Who did you bring in to collaborate on this record?

The credits listing on this record is long — every contributor brought something uniquely powerful to the process. I’m fortunate to work with such inspiring collaborators.

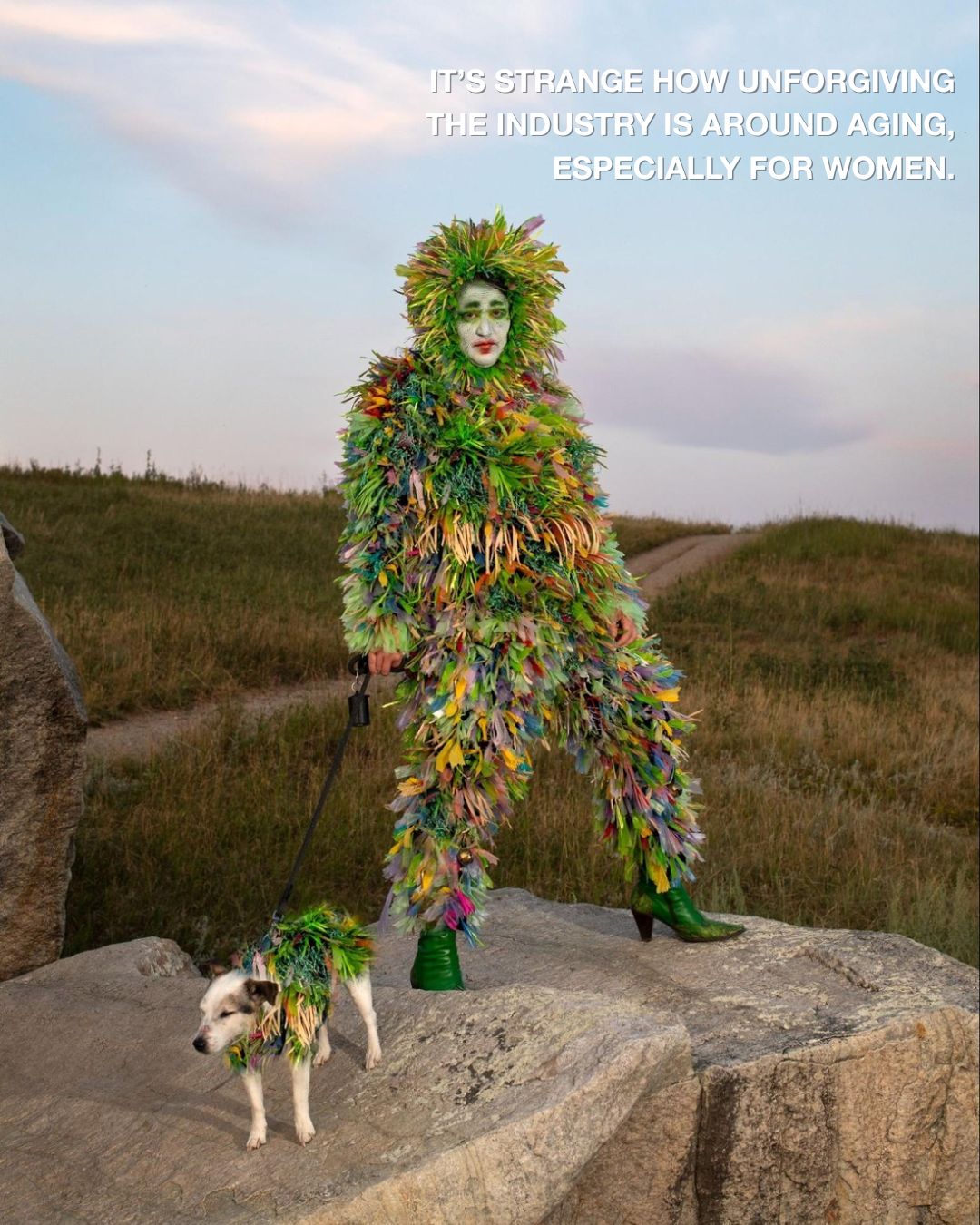

I loved the feathery creature costume on the album cover—can you talk about where it came from?

I also work in film and TV, especially in costumes. That outfit blends skills from costume work with research into English folk traditions, where my family is from. The album explores family history, so I wanted a look inspired by folklore—part ghillie suit, part Morris dancer. I was thinking of figures like the Green Man or Burry Man.

I found this rock near my house in Confluence Park that looks like the Split Rock in the Orkney Islands, where my family’s from. That tied into ideas of the wheel of the year, seasonal cycles, and the Scottish goddess of storms, the Cailleach. It all clicked thematically.

Photographer Heather Saitz took the cover photo and some promos. I made the costumes and painted the backdrops. Each element feels like an installation. I see the sound visually—each album is its own tarot card.

What relationship do you see between “death” and “the fool”?

Both my dad and my partner’s mom died after the pandemic, so the album is very much about death. Mourning involves exploring shared histories. Going through ephemera, I kept wondering, “Who do I tell these stories to?” I don’t have kids. With my dad especially, I wanted to engage with his life and ideas through my art—not just sit crying on the floor with old papers.

Humour shows up too—it’s weird how grief opens the door for silliness. There’s absurdity in confronting mortality. You wonder how you ended up where you are, how much time you have left. That can spark urgency: why do we wait to do what matters?

When someone’s dying, you’re completely in the moment. That’s actually beautiful. Some tracks on the album are improvised, to show how being present—whether improvising or building metaphor—is all part of my artistic process. There’s no one right way.

I wanted to ask about the song based on your grandmother’s poem that you’d found.

I’ve done archival work, and I’m a bit of a hoarder when it comes to family stuff. Going through my dad’s things—letters from the ’60s, old photos—I stumbled on my grandmother’s poem. She had a degree in drama and loved the arts, but never really published. I wanted to honour her and her son, my uncle Martin, who was a birdwatcher.

The poem’s original title was long, something like “For the Occasion of the Death of a Dying Young Adult.” But the line “the birds never left” stood out—it was perfect for the song title and connected beautifully to who he was.

Photo by Heather Saitz

You mention aging in your artist bio — can you speak more to that?

It’s strange how unforgiving the industry is around aging, especially for women. Statistically, people improve with age—you gain experience and depth. I’ve never focused on love songs in the conventional sense. My love songs are for family, for stories I want to preserve.

I recorded a full album at 19, but had no idea how to release it. Since then, the process has changed every time. With social media, there’s pressure to seem young and current. But many cultures value older women as knowledge-keepers. I didn’t want to deny aging—I wanted to embrace it, to present myself as someone still vital, still creating.

I’ve seen the harmful effects of the cult of youth up close through my work in the Hollywood-adjacent world. I wanted to bring a different icon to the table. I’ve got years more of music to make.

You named your project Hermitess. Do you feel the need to isolate to create?

I like to hyperfocus and immerse myself in world-building. That cloud of ideas over my head needs space and time to condense into something tangible. I’ve had good funding lately, which helped realize bigger ideas—videos, production, etc.

I named the project Hermitess after leaving bands where things didn’t quite align. And as a woman, you often end up in supportive roles. A friend once joked I was scared to be alone with my own work. That really stuck with me. So I decided to do it.

You’ve done a number of residencies—do they feel like “magic cave” moments?

Definitely. There’s this myth that songs come when they come, but with all the distractions now, that’s rare. Residencies give me space to work like a job. I just commit to writing a song each day, even if I don’t keep it. Just staying in that practice is productive.

I usually have fragments—poems, ideas—but you still have to sit down and build the thing. Residencies let me do that without daily distractions. I can finally stack the blocks.

You’ve said this album is in conversation with your ancestors. What do you think they’d say after hearing it?

I think they’d just be grateful to be remembered and have their stories told right. I think their ears would be ringing on the other side. More specifically with my dad, I think he would really appreciate me telling the stories that he used to tell where I would roll my eyes. I think he’d think, “Oh, she did actually hear the things that I cared about and wanted to share with the world. And now she’s doing that herself, like taking up the mantle of some of those stories.”

And also, why wouldn’t you? Good stories—they kind of ask to be told, right?

By Stephan Boissonneault

With There Is Nothing In The Dark That Isn’t There In The Light, the veteran vocalist leans into intimate, searching folk.

By Sam Hendriks

A refined turn toward clarity reveals Melody Prochet at her most grounded and assured.

By Judynn Valcin

Inside the Montréal musician’s shift toward ease, openness, and a sound that refuses to collapse even as it teeters.