The Other Side of Prison: In Conversation With Filmmaker Jafar Panahi

The Palme d’Or-winning director of It Was Just an Accident discusses the blurred lines between social and political cinema.

by Prabhjot Bains

- Published on

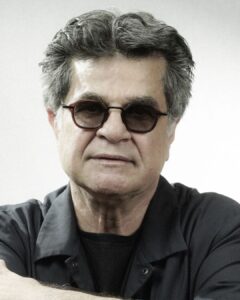

For Jafar Panahi, the premier dissident filmmaker of our time, cinema remains one of our few remaining lines to the truth—a medium that unites people in parsing fact from fiction. Across a career of politically charged and socially conscious films, Panahi has continually clashed with Iran’s theocratic regime, smuggling films out of his native country during a 20-year filmmaking ban and, more recently, enduring a stifling prison sentence.

Panahi’s latest project, the Palme d’Or-winning It was Just an Accident, marks his first post-ban film, but in true defiant fashion, he chose to make it outside of official channels, to avoid submitting it for state approval. Inspired by Panahi’s own experiences as a political prisoner, It was Just an Accident follows Vahid (Vahid Mobasseri), a formerly imprisoned auto mechanic, who abducts a man with a prosthetic leg whom he supposedly recognizes as one of his former torturers. Unsure whether he’s nabbed the right man, he visits other ex-political prisoners—including a wedding photographer and a soon-to-be bride—to validate his act of vengeance.

Unfolding as a humanist comedy of errors, Panahi’s film sifts through a bevy of humorous, lived-in character interactions and confessions, cultivating a powerful community of shared suffering and a haunting portrait of the decisions everyday Iranians have to make in response to living under a repressive, morally bankrupt theocracy.

In many ways, It Was Just an Accident is Panahi’s most personal film to date. During the Toronto International Film Festival, he tells RANGE, “Most of these stories in the film, I have heard when I was in prison.” With a gravelly voice that teems with both melancholy and hard-fought experience, he adds, “Most of these characters, too, I have met inside and outside of prison, so they could be real people.” With such startling commitment to authenticity, Panahi confronts troubling, ethically grey questions head-on, putting audiences in the hot seat of finding the answers for themselves.

Yet, as emotionally shattering as Panahi’s film is, it’s also undoubtedly his most humorous endeavour. Though it’s not exactly the first reaction he intended to elicit. He notes, “I really didn’t have an intention of making my film comedic and sometimes I thought when I watched it with an audience: is it really funny at this point?”

He continues, “But this happened automatically, because I make my films in the style of realism… and the cultural characteristics of the Iranian people, anything they do has humour embedded in them—and in the most difficult circumstances they don’t let go of jokes.” In a sense, every punchline or humorous interjection doubles as an act of rebellion in It was Just an Accident, as its characters consistently hold onto their humanity even though they’ve effectively been stripped of it. Even though Panahi didn’t set out to make a comedy, the humour he taps into continues to carry a deeper, starker meaning.

Yet, Panahi hardly found anything to laugh about during the turbulent production of the film, which routinely met roadblocks courtesy of the regime. Though if anything, Panahi’s dissident art lifestyle more than prepared him for the challenge. “The past four or five films allowed me to make it easier on myself,” Panahi says. “Those experiences had taught me what security measures I need to take for the film to survive.”

Still, some hurdles are never easy to jump over. Panahi notes that the production was severely threatened by representatives of the regime. “Two days before the shooting was over, they raided the set and didn’t let us continue…they took some of the team members for interrogation and they gave them an ultimatum that they can no longer work with me.

“So, we stopped the project for a month, then we went back in one day and tried to make all the shots that were left.” In a world where it’s already difficult to get independent film into theatres, such debilitating political barriers make the mere existence of Panahi’s film feel, much in the vein of its title, like an accidental miracle.

From many viewpoints, It was Just an Accident dons its political fabric proudly and loudly. But famously, Panahi has rejected the label of “political filmmaker,” opting instead for more socially conscious descriptors. “I’ve always said I’m a socially engaged filmmaker. Outside of my films, I have taken political sides, but in my films, I have tried to stay committed to a socially engaged cinema.” He continues, “We have to give a definition to ‘political cinema,’ as political cinema usually divides people between good and bad.”

As a result, Panahi notes we have to ask “why is this person good? Is it because this person agrees with my beliefs and my party? Or is another person bad because they disagree with my party and beliefs?” He notes that in “socially engaged cinema, we don’t have purely good or bad people; you allow everyone to speak.”

Now leaning forward in his chair and gesturing to his interpreter, Panahi asserts “I have never said I am, or I am not a political person, I have said I’m a socially engaged filmmaker, everyone can have different interpretations of this and write it based on what they hear. My outward personality is different than my inward filmmaker personality…outside filmmaking, I can be a political person, I can take political sides, but in my films I do not.”

Whether or not audiences buy into his debatable stance is of little consequence, as It was Just an Accident triumphantly succeeds as a direct connection to the truth. Now, sitting back in his chair with self-assured confidence, Panahi can rest knowing his film will serve as a challenging but honest reclamation of history-in-the-making—a tribute to fiction not as a means of obscuring truth but crystallizing it.

It Was Just an Accident is in theatres on Oct. 24

By Glenn Alderson

A deep-listening session reveals how Apple Music’s sonic innovation reshapes the way we hear.

By Cam Delisle

Dominic Weintraub and Hugo Williams take audiences on a treadmill-fueled ride through the chaos and hope of modern life.