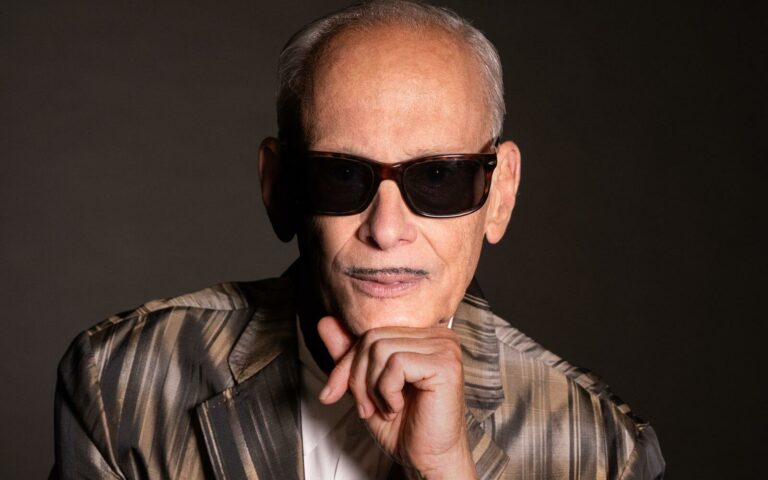

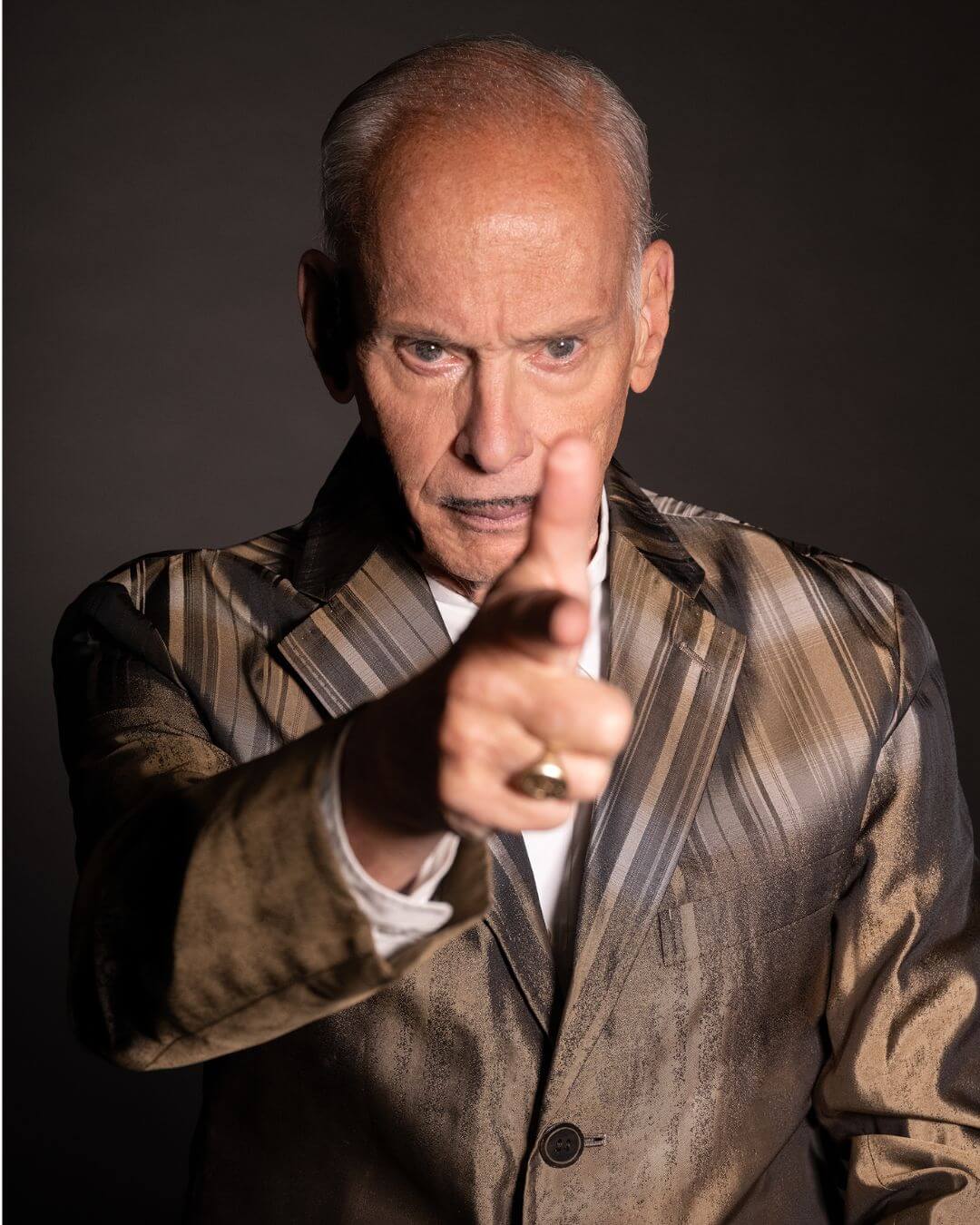

John Waters Explores the Art of Laughing at Yourself

The subversive filmmaker who changed American cinema diagnoses the left as painfully self-serious, prescribes laughter as the best medicine.

by Maggie McPhee

Photo by Greg Gorman

- Published on

John Waters writes until noon every day. He’s a wellspring of wisdom, a prolific pervert, a one-man filth factory. His outpour has spawned 18 screenplays, eight books, innumerable essays, and an annual spoken word show. Part stand-up, part confessional, part polemic, these performances pluck straight from the glamorous gutter of Waters’ mind.

The cult filmmaker who has brought us classics including Pink Flamingos, Cry Baby, and Hairspray roots his entertainment style in vaudeville. “I’m a carny,” he tells RANGE. “In the early days, I toured with Divine to colleges because we didn’t have any money to advertise. We gave out door prizes, I always had carnival-type things to get people to come see my movies.”

Growing up in Baltimore, he’d skip school to bask in the director-cum-salesman shticks of William Castle and Kroger Babb, “who had nurses selling sex education literature and ambulances out front to take away shocked patrons.” For Waters, cinema should pour past the confines of the screen, into aisles and onto sidewalks.

His one-man shows allow him to make those boundaries more porous and revive an old-school artform for the modern day. “I’m just excited,” he shares. “I’d love to meet the new audience, see the new kids, and I’m really happy when they are kids because then that’s the new generation I somehow sucked in.”

Waters’ latest act will grace Canadian stages this month. The showbill promises to teach audiences “how to reinvent the movie business, embrace stupidity in an intellectual way, and even go beyond the limits of sexual transgression.” Though careful not to divulge any spoilers, Waters says this monologue was inspired by “the new sexual revolution that suddenly made me feel like an NC-17 neuter.”

“I used to know all the answers,” he continues. “You don’t need me anymore. You’ve thought up a new sexual revolution that has made all sides nervous. You have gone even further than we did in the sexual revolution of the sixties. So I salute you.”

The iconoclast, who stunned audiences in the 1970s by shattering every conceivable taboo — incest, shit-eating, toe-licking; if it exists, there’s a John Waters scene about it — finds himself at a crossroads. “My comedy has always been ‘What can you get away with?’ And I have never been cancelled or had any hassle. If you fear censorship these days, it’s from the left, not the right, because the right gave up on me a long time ago,” he says. “But I find myself in the middle now, which is the most radical I’ve ever felt in my entire life, because the extremes of the left seem self-righteous, even though I agree with a lot of them. And the right is just so ridiculous.”

Waters finds himself smack in the middle of a paradox. On the one hand, the internet makes all sorts of nasty shit accessible to the masses. We’ve grown numb to the electro-shock torture of daily news. We’re jaded by day one, practically born with a cigarette dangling from the mouth.

“There’s no taboos left to break.”

— John Waters

“There’s no taboos left to break. I mean, everything’s been done. So there’s really no such thing as an exploitation movie anymore. I guess Cocaine Bear was the last real one. And it was a great idea and a great campaign and an okay movie,” he says. “That was the next generation’s Snakes On a Plane. Neither were hits.”

On the other hand, political correctness constrains the possibilities for dealing with this deranged world through humour. “Well, there’s taboos now,” he admits. “But all the taboos are left-wing taboos — that you can’t joke about anything. And I make fun of myself from the very beginning. That’s the first thing I make fun of. And I make fun of things I love, not hate. And I think that is very different in tone, and why I’ve lasted this long.”

Without comedy, we limit our ability to discover a common humanity with those seated across the aisle. “All humour is political,” says Waters, who’s been slinging jokes for half a century. “You cross over if you can make people laugh. That’s the only way you can get people to come anywhere or change their mind or open up to try something new.”

Waters isn’t prescribing punching down. “You never make the enemy feel stupid. You don’t win that way. Even if they are stupid, you make them feel smart and they’ll listen.” Rather, he’s suggesting we aim those punches at ourselves and stop taking everything so seriously.

“People are afraid to laugh at anything now, that’s the thing. Although they’ll do it in private. They won’t do it in public, no matter what your politics are. Learn to laugh at yourself first,” he says. “Because I make fun of the rules that so-called outsiders live by. Not the rules of our parents that we fled a long time ago. And what’s so amazing to me is the outsiders have more rules now than my parents did growing up.”

Waters launched wrecking balls at conservative America. He lampooned their homophobia by reclaiming their worst assumptions, revealing their bigotry as grotesque projections of repressed Wonderbread psyches. Now, he hopes to pass that artillery on to the next generation.

“What they need to do is wreck what came before. Every possible thing that happens in contemporary art wrecks the movement that was before them. Pop art wrecks abstract expressionism, minimalism wrecked that, video art wrecked this. And now it’s politically correct art, which would be easy to wreck but no fun,” he says. “That’s the challenge: to come up with a new way to wreck the serious political correctness, but still be good and open-minded and go even further in the same direction.”

By Glenn Alderson

A deep-listening session reveals how Apple Music’s sonic innovation reshapes the way we hear.

By Cam Delisle

Dominic Weintraub and Hugo Williams take audiences on a treadmill-fueled ride through the chaos and hope of modern life.