By Stephan Boissonneault

With There Is Nothing In The Dark That Isn’t There In The Light, the veteran vocalist leans into intimate, searching folk.

Thunderball, the band’s 31st album, is out April 18 via Ipecac Recordings and features five songs of what fans have come to expect from the underground behemoths: strident, abrasive guitars and doomy vocals set over a rhythm section that stomps relentlessly forward like an opiated elephant.

Mike Dillard, the band’s very first drummer, is back in the fold on percussion, making Thunderball as close as contemporary fans will get to experiencing Melvins in their very first variation. The band, now billed as Melvins 1983 for the occasion, is just Osborne and Dillard fielding the instruments. The rest of the collaborators on Thunderball are credited with only contributing “creepy machine vocals, upright bass and hand gestures.”

For the uninitiated, here’s a brief run-through of the Melvins’ long and storied history. The band was started in 1983, in Montesano, a small coastal town in Washington, by childhood friends who felt hemmed in by the strictures of isolated “dangerous redneck” places. After spending a few years playing around writing hardcore music, Melvins began stretching out their sound, turning punk songs into long, heaving, and supremely noisy dirges. Their sound, dubbed “sludge punk,” was born. After relocating to California, they began a productive streak of albums and tours that has continued to this day.

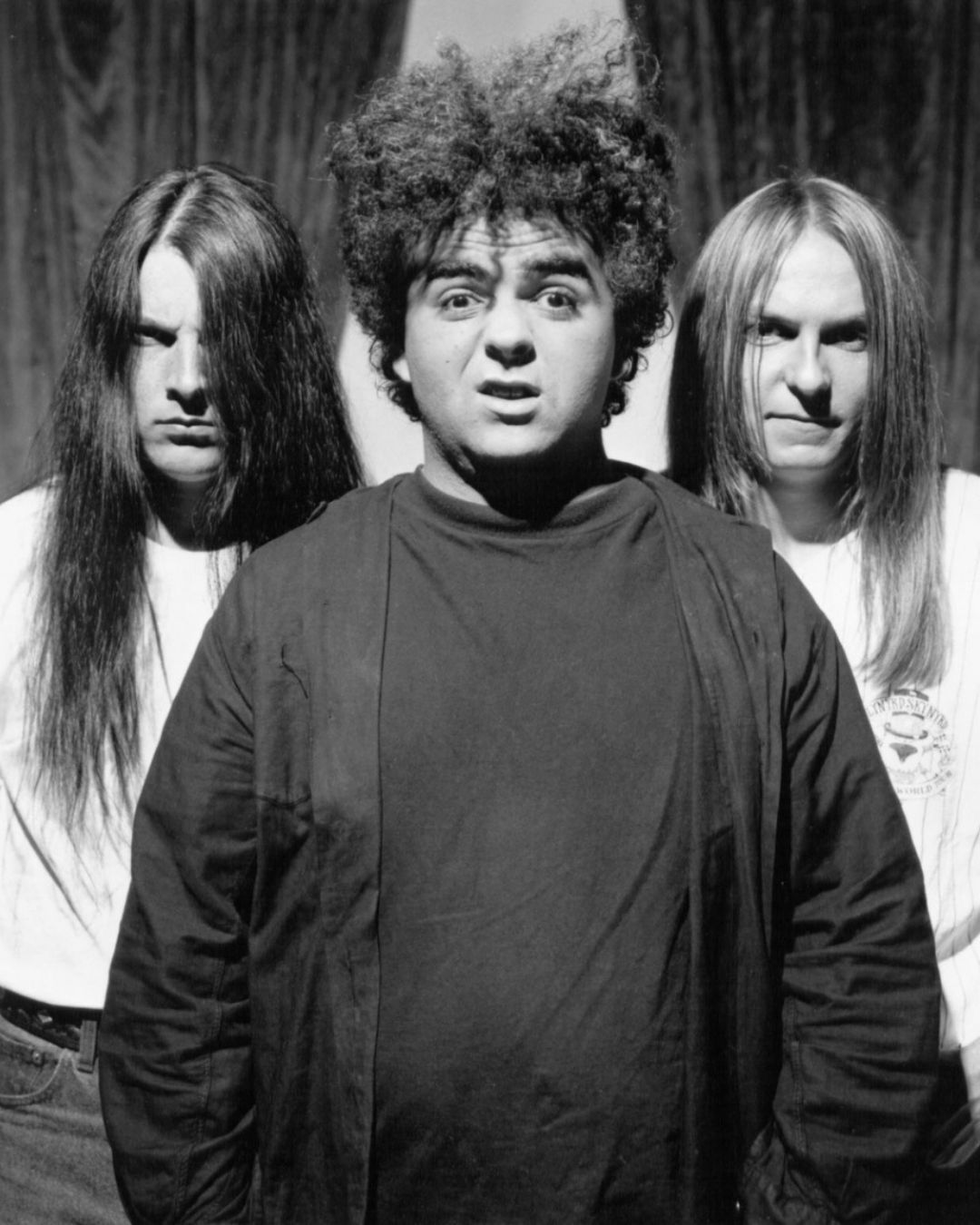

Melvins circa 1993 — (L-R) Mark Deutrom, Buzz Osborne, Dale Crover

In 1990, they were signed to Atlantic, at a time when record executives threw giant cheques at young guitar bands in hopes of drawing out another “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” and then promptly dumped them when the dividends took too long or were too few. The band did nothing to curb their sonic brutality, and more or less proceeded as they had before. Predictably, the writing was on the wall, and after three albums, they left. “I’m too big, too weird-looking. We didn’t look like wounded junkies, so they wanted nothing from us,” Osborne says of the stark contrast between himself and the six-pack-sporting vocalists of grunge music’s heyday.

Instead, Melvins looked underground. Their first home after a major contract was Amphetamine Reptile, a hallowed label that, at the time, was harnessing the best of noise punk, giving home to the most feral and non-commercial aspects of alternative music. By 1999, they had signed with Ipecac, an artist-run and artist-centric label started by Greg Werckman (former manager of Alternative Tentacles) and Mike Patton (Faith No More, Mr. Bungle, Tomahawk, and countless others), a move that would prove to be permanent.

“My experience with Sub Pop, much like with other labels, is 100 per cent different from my relationship with Ipecac. Ipecac keeps it good and simple.”

After an endlessly revolving door of bassists, collaborations with Jello Biafra, Butthole Surfers, and Napalm Death, a song on the True Detective soundtrack and many other moments in a long, uninterrupted tenure, here we are, more than 40 years into the life of one of the most imperishable bands in music history. They are still here, still on the road, still cutting records at a steady click. Unlike Swans or The Fall, Melvins hold little animosity towards line-up changes or their vast back-catalogue, and the band makes a conscious choice to touch on all of their material as their tours roll on.

“When I was a kid and I went to see the Kinks in the early ‘80s, I would have been pissed off if they didn’t play “You Really Got Me,” Osborne chuckles.

Again, he appears to be exactly the person his reputation suggests he is. A virtuoso, and a loving and loveable curmudgeon. He rants willingly and often, about dozens of people, bands, and concepts, but there’s little bitterness felt in any of it. It’s difficult to blame him for having passive grievances after so many years in the grind, losing friends and witnessing the sociopathic tendencies of the music industry. Despite being around some of the biggest tectonic shifts in music, Osborne has happily lived in his own carved out space, rarely feeling the need to compromise himself with anything outside it.

“I’m not good at networking, at parties, at glad-handing. I’ve lived in LA for years, and I’ve never been to a Grammy party or a movie premiere,” he says. “Yes, I would have liked to meet the guys from Throbbing Gristle, but I just never find myself in a position to make something like that happen.”

Melvins cira 2021 — (L-R) Mike Dillard, Dale Crover, and Buzz Osborne.

Truth is, after more than four decades, Melvins are more than just a rock band. They have been and continue to be a huge point of influence and inspiration for musicians, not just in how to survive the recording industry, but in how to thrive against its tides. They were there for all of its critical shifts: the explosion of grunge and the CD era, the field being flooded with unthinkable amounts of money, and the ensuing crash as online piracy shook the industry at its very foundations. The rise and fall of MTV, nu-metal, post-grunge, Nickelback, frat punk, the third coming of ska, noxious levels of EDM and ambient, poptimism, Swifties, and Kanye West – they put their heads down, worked, toured, and bulldozed through it all, somehow emerging wholly themselves on the other side.

Osborne remains pointedly cheeky and modest about his own endurance, and sums up his life, which seems so wild and fluctuating to outsiders, in the most simplistic terms: “I play golf, do photography, I exercise, I love reading. I have been married for 31 years, and we still talk about art and music every single day. I don’t need alarm clocks in the morning, because I wake up at sunrise, ready to fucking go. I’m too busy for crisis.”

By Stephan Boissonneault

With There Is Nothing In The Dark That Isn’t There In The Light, the veteran vocalist leans into intimate, searching folk.

By Sam Hendriks

A refined turn toward clarity reveals Melody Prochet at her most grounded and assured.

By Judynn Valcin

Inside the Montréal musician’s shift toward ease, openness, and a sound that refuses to collapse even as it teeters.