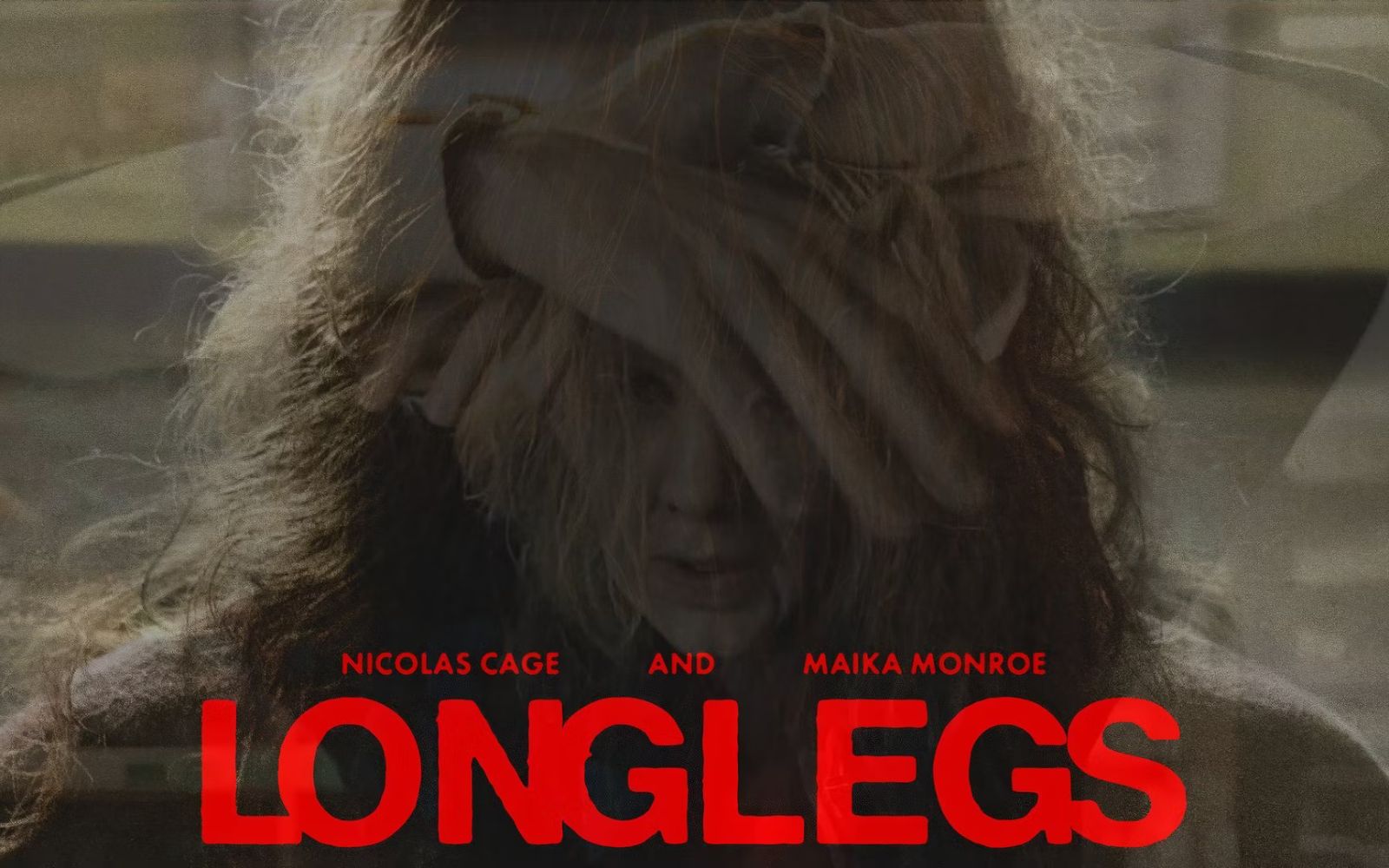

Longlegs director Osgood Perkins is a Caretaker of Dread

The filmmaker opens up on transforming simple truths into baroque nightmares and Nicolas Cage into one of the most memorable villains in horror history.

by Maggie McPhee

- Published on

Osgood Perkins can’t define an Osgood Perkins film. In his view, filmmaking is a collective process. Still, he’s delivered some of the most distinctive horror films of the last decade, simmering slow burns that centre female protagonists, ambiguity, and atmosphere. All of which churn like a whirlpool slowly, steadily sucking you into the deep.

Longlegs, his fourth film, stars Maika Monroe and Nicolas Cage in a game of cat and mouse, Monroe in pursuit as rookie FBI agent Lee Harker and Cage always slightly out of reach as “Longlegs,” a serial killer somehow connected to a string of gruesome familicide-suicides — fathers slaughtering their loved ones with no sign of Longlegs ever entering the premises. An obsession with the daughters of these families and their ninth birthdays consumes Longlegs who, in the rare scenes in which he comes into contact with young girls, acts like a sick man under a spell. And the closer Harker gets to Longlegs, the closer she comes to the vertiginous abyss, at the bottom of which lies a dark secret about her own family.

Perkins pulls the thread of the classic police procedural thriller until it unravels into something unrecognisable. He interweaves examinations of human psychology with elements of the supernatural into a delicate webbing that floats on the membrane of life as we know it. The cop versus killer formula, Perkins discovered, offered the perfect grappling hook for his descent into the unknown. Marrying the mundane details of a manhunt with the esoteric uncertainties of black magic meant there would always be a tether to hard evidence, which would engage audiences while emphasising just how desperately they cling to absolutes.

“There was a moment where it was like, ‘why doesn’t everybody do this?” Perkins tells RANGE. “The great thing about horror generally and the supernatural especially is that you get to open up the world to anything you want to do. That’s why the horror genre for me is so engaging and interesting. The landscape is infinite. It’s everything. Every rule is for you to design. You can go in any direction, utilise any emotion, any kind of shape, colour, creature, fact, fiction, mythology — it’s all at your fingertips… You can come in the door with something very tangible, and juxtapose that against, like, ‘no, we don’t really know anything about how shit works.’”

To avoid being swallowed up by this infinitude, Perkins keeps himself connected to a certainty, too, when setting out to make a movie. For Longlegs, he was guided by the idea that parents tell their children lies hoping to protect them that go on to shape them in unintended ways. “It’s a simple truth, it’s not complicated, it’s not clever, it’s not esoteric or opaque,” he says of his process. “It’s a struggle, and as a parent, and about my own parents, this struggle of: don’t you protect your kid no matter what? And sometimes you got to really obscure the truth of things. And sometimes you got to do some shit that you don’t think is that great. And this movie is the most extreme version of that.”

But his explorations of single ideas are anything but straightforward. The theme of parenthood ricochets through the film like an echo. For the first two acts, Harker’s own mother appears only as a thin voice over the telephone. And Longlegs goes so far in his infatuation with female children as to propagate his own in the form of lifesize dolls. These dualities between good and bad parenting emerge in the yin-yang characterization of the reticent and repressed Harker and Longlegs, a madman undone at the seams. Monroe and Cage, both genre heavyweights, deliver career best performances. Where Monroe perfects a subtle and controlled performance, Cage goes full id. Together, they are positive and negative space, and their collaboration is the full picture.

“To be honest with you, everything was written. It all starts on the page,” Perkins says of preparing the actors. “I offered Nick: you can do whatever you want, improvise, I don’t care. And he was like, ‘no, no, no, man, I’m gonna do everything that you wrote just the way you wrote it.’ And I was like, ‘well, that works too.’”

“I’ve only ever experienced actors who really care about what they do and really care about servicing the text and servicing the project,” he continues. “And so I leave them alone. Why would I tell them what to do? Why would I tell Nicolas Cage what to do? If he agrees with the text, then it’s 99.9% of the way there.”

“Why would I tell Nicolas Cage what to do?”

— Osgood Perkins

Though it begins with the script, the final product bears no resemblance to what Perkins envisioned when writing dialogue. Cage’s Longlegs, though true to the text, is all Cage. That, for Perkins, is the joy of filmmaking. Teamwork transcends one person’s idea. Longlegs feels so layered and complex because of the talented crew who put themselves in its fabric, comprised of the connections between their care, craft, and collaboration.

“The only way I know how to act is nurturing and gentle,” says Perkins on his directorial style. “Like caretaking. Caretaking the other people who are making the same movie as I am because they want it to be great too. They’re not just doing their homework, they care, they’re invested. Because it’s also theirs. And I say to other people who work on the movie all the time: ‘this is as much yours as it is mine.’ I don’t say it’s an Oz Perkins film. I don’t know what that means.”

By Prabhjot Bains

Danny Boyle’s latest zombie epic feels thrillingly countercultural and brazenly juvenile.

By Cam Delisle

The music and culture curators are redefining Québec City’s pulse with four festivals, multiple venues, and a vision that goes far beyond FEQ.