By Megan Magdalena

A sold-out night at the Vogue Theatre brought Warped Tour memories roaring back.

It’s a fact that Black culture contributes widely to Canada’s national music profile – even though the icons driving it forward aren’t as well recorded. From bluegrass tours across the Maritimes to creating electronic music in Muskoka, let’s take a look at some significant moments Black Canadians have contributed to music culture.

Black Canadians had settled in the Maritimes as early as the 1700s, when many free Blacks made the trek from America in search of prosperity. With that came the impact of Black musicians on the popular genre du jour: bluegrass. Although the history of Black bluegrass players is sparsely recorded, their contributions can’t be overlooked.

Harry Cromwell (left) and Brent Williams. (Photo courtesy Brent Williams)

Brent Williams grew up being thrilled by the bluegrass duo Jerry and Sky while watching the Grand Ole Opry. He first plucked a guitar around six years of age and knew he wanted to wow audiences in the same way as his idols. He and his friend, a fellow guitarist by the name of Harry Cromwell who lived next door, began playing together. By the time they were old enough to be in clubs, they were earning recognition in local talent shows.

A chance encounter with fellow Nova Scotian Vic Mullen led the two boys to touring the Maritimes as a trio. They set out touring the Maritimes as the Birch Mountain Boys and are believed to be one of the first bands to play and record bluegrass music in Canada. The touring was short-lived, as the late 1950s proved that the ascendant genre of rock and roll was king. Vic Mullen went on to create music for television, while Williams and Cromwell continued on the road as a duo and continued to make guest appearances on Mullen’s shows.

Williams, now 79, describes his early years in Nova Scotia as “the most precious and enjoyable times of my life.” He still works as a musician and is currently working on his memoir from his home in Lakefield, Ontario. “We kind of paved the road for Canadian artists that have done well today,” Williams tells RANGE. “We didn’t realize what we were doing at the time, but that’s what we’re known for today.”

In the 1960s, Caribbean immigrants arrived in Canada amid the immigration system relaxing its policies, bringing with them the sights and sounds of the islands. Local clubs popped up on the hip Yonge Street strip and spots like the West Indian Federation Club (WIF Club) and Club Jamaica, near today’s Eaton Centre, became instrumental social spaces for Canada’s burgeoning Caribbean community.

At Club Jamaica, the office was a consulate, with owners assisting newcomers to Canada through the immigration process. The kitchen was a culinary school, where volunteers taught others to make patties and other delicacies. Plus, the club owners doubled as international show promoters, calling up musicians from the islands to come and perform. Legends like keyboardist Jackie Mitoo played for Club Jamaica’s house band, the Sheiks. Some of them, like Bob Williams, vocalist in the duo Bob & Wisdom, never left. Arriving in 1967, he dove right into Toronto’s local music scene, becoming studio fixtures in the band Jo-Jo & the Fugitives.

At Club Jamaica, the office was a consulate, with owners assisting newcomers to Canada through the immigration process. The kitchen was a culinary school, where volunteers taught others to make patties and other delicacies. Plus, the club owners doubled as international show promoters, calling up musicians from the islands to come and perform. Legends like keyboardist Jackie Mitoo played for Club Jamaica’s house band, the Sheiks. Some of them, like Bob Williams, vocalist in the duo Bob & Wisdom, never left. Arriving in 1967, he dove right into Toronto’s local music scene, becoming studio fixtures in the band Jo-Jo & the Fugitives.

Williams reminisces about hopping off stage after a Friday night performance. The bands would party through the weekend, club hopping down the Yonge strip and linking up with other musicians who had just finished their gigs at Le Coq D’Or, Ronnie Hawkin’s Hawk’s Nest or another late night haunt. “The music scene was alive and kicking and they were all in walking distance,” says Williams. The WIF Club closed in 1967 when it burned down due to a fire in a neighbouring store.

Although he was born and raised in Philadelphia, Beverly Glenn-Copeland’s years in Canada coloured much of his musical background. In 1961, he enrolled in McGill University, becoming one of its first Black students in the faculty of music. Facing discrimination for being in an open lesbian relationship – Copeland began identifying as a trans man in 2002 – the vitriol led him to drop out.

Photo: Juri Hiensch

After leaving McGill, he went on to write music and appear on screen in the iconic children’s show Mr. Dressup for more than 20 years. Glenn-Copeland found solitude in woodsy Muskoka, Ontario in the 1980s. In a 2020 interview with the New Yorker, Glenn-Copeland said, “the natural world” was his companion at the time, along with a computer. With those companions by his side, Glenn-Copeland holed up and taught himself to make digital music. The result, 1986’s Keyboard Fantasies, is an electronic masterwork informed by his surroundings and featuring mantric lyrics.

In 2016, an influential Japanese music collector named Ryota Masuko reached out to Glenn-Copeland. Masuko had stumbled across a copy of Keyboard Fantasies and asked to purchase the remaining stock of the electronic compositions. This sparked international interest in Glenn-Copeland’s work, introducing it to a new generation. Keyboard Fantasies Reimagined was released in 2021, with remixes and reworks by the likes of modern innovators Bon Iver, Arca and Blood Orange.

By 1967, Toronto’s Caribbean community was 12,000 strong and growing. Coinciding with Canada’s centennial celebration, a small committee came together to devise a cultural festival mirroring the carnivals and parades of Barbados, Trinidad and Jamaica. The result was a festival in Toronto Island Park full of steel-pan drumming, street dancing and lavish masquerade costumes. The event was a hit, bringing more than 50,000 people to the Islands.

Sam Cole, the festival chairman, told Toronto Star that the festival took nine months of planning between committee members—a doctor, two lawyers, a town planner and a teacher, all of whom were immigrants from the Caribbean living and working in Toronto. “We made a few mistakes,” said Cole of the committee’s efforts. “But it was worth it. It’s been very successful and next time we’ll know what pitfalls to avoid.”

Sam Cole, the festival chairman, told Toronto Star that the festival took nine months of planning between committee members—a doctor, two lawyers, a town planner and a teacher, all of whom were immigrants from the Caribbean living and working in Toronto. “We made a few mistakes,” said Cole of the committee’s efforts. “But it was worth it. It’s been very successful and next time we’ll know what pitfalls to avoid.”

Successful is an understatement. The inaugural festival was so popular that off-duty ferry crews were called in to move loads of people to the Islands, running well past their scheduled times. Caribana, now known as the Toronto Caribbean Carnival, has since become a yearly staple of Toronto summers, cementing Caribbean influence in Canada.

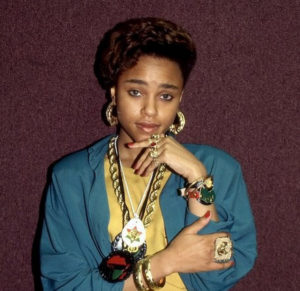

Before Canada had any image of generating successful rappers, Michie Mee was the first person to break down doors for MCs from the North. She began performing at 14, fusing her rap ability with dancehall elements from her Jamaican heritage while making frequent trips to New York, staying at her aunt’s house and soaking up the culture of the Bronx in the 1980s.

Photo Courtesy of Ernie Paniccioli

In 2015, she reminisced with VICE on making the case for Canadian rap in the 1980s. “I was convincing [Boogie Down Productions’] Scott La Rock and KRS-One that I rapped and that there was rap music coming from Canada.” In 1987, Mee and producer LA Luv paired up to release “Elements of Style,” a single that made it to a compilation of Canadian hip-hop called Break’n Out.

The success of “Elements of Style” in the US brought her back to New York with interest from major labels. She went on to sign to First Priority Music, becoming the first in a long string of Canadian rappers to make record deals with American music labels. She also contributed to other genres as a vocalist in the Toronto-based metal-reggae fusion act Raggadeath.

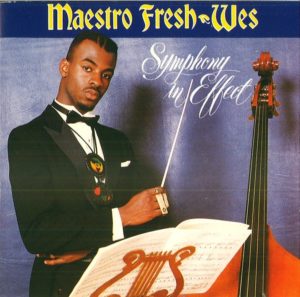

In a 1990 edition of the Toronto Star, rapper Maestro Fresh Wes spoke on the surge in popularity of his then-nascent genre. “To the outside, people might not think rap has really arrived in Canada. But to people inside, the people who know what time it is, rap has been on top for a while now.” The pioneering MC had released his debut album, Symphony in Effect, only a year earlier, earning the first platinum plaque for a Black Canadian.

In a 1990 edition of the Toronto Star, rapper Maestro Fresh Wes spoke on the surge in popularity of his then-nascent genre. “To the outside, people might not think rap has really arrived in Canada. But to people inside, the people who know what time it is, rap has been on top for a while now.” The pioneering MC had released his debut album, Symphony in Effect, only a year earlier, earning the first platinum plaque for a Black Canadian.

The lead single, “Let Your Backbone Slide,” was nominated for Best Dance Recording at the 1990 Juno Awards, and Wes’ output and lasting influence also paved the way for future artists. The success of his singles led the Junos to create a category for Best Rap Recording in 1991, which Maestro Fresh Wes won for Symphony in Effect. Looking back at his Juno win in an interview with CBC, Maestro Fresh Wes said “I was representing Black music in Canada. I knew it was bigger than hip-hop.”

The fight for Canada’s first Black-owned radio station began with Fitzroy Gordon. Gordon started his career in broadcasting as a late night host on CHIN FM throughout the 90s, aiming his focus toward Canada’s Caribbean community and playing everything from R&B to smooth jazz and soca.

Fitzroy Gordon

When he left CHIN in 1998, he set out with the goal of using his platform to create an entire radio station catered to the Caribbean community. Getting a broadcasting license proved to be a challenge, as he competed with the institutional power of the CRTC, Canada’s regulating body for radio. The CRTC turned down his first application in 2001. Gordon recalled feeling encouraged, “knowing that I came so close to getting the license.”

Resolved, Gordon poised himself to prepare a new application, this time receiving a partial license in 2009 that came with a catch: he had to find a frequency himself. Gordon’s frequency, 98.7, neighboured the CBC’s 99.1, and Canada’s national media overlords refused to share the airwaves. So Gordon took his fight to the government.

“I lost a lot of things,” Gordon told Canadian Immigrant in 2012. “I lost my car, home, relationships, I lost my friends — because a lot of people thought I was wasting my time, and the CBC or the government will not allow a small man like me to get a radio station in this important region of Southern Ontario.”

Gordon spent all his personal savings fighting for his platform. That fight finally paid off in November 2011 when the station was officially licensed after more than a decade of litigation. The inaugural broadcast was symbolically led with the song “I Can See Clearly Now,” by Jimmy Cliff. Gordon resumed hosting for G98.7 and remained an important fixture of radio until his death in 2019.

In 2003, York University hosted the first conference researching Black music culture in Canada. Leslie Sanders, a professor of Black Canadian literature, said, “Canadian Black music is rich in its diversity, it deserves to be more widely known, and I’m delighted that this conference is examining the development and its future.”

The three-day conference featured roundtables on the history of reggae, calypso, hip-hop and several other genres, bringing together researchers, critics and artists discussing the history and establishment of Black music in Canada.

While many Caribbean-Canadians made their mark through the 60s and 70s, many of the recordings and institutions were lost to time. Venues like Club Jamaica and the WIF Club that populated the Yonge Street strip have since disappeared, while home-recorded and self-promoted 45s were scattered through independent record shops and personal collections.

It wasn’t until the release of Jamaica to Toronto: Soul Funk & Reggae 1967-1974 that the essential recordings of the time were canonized and compiled into a series of tapes with the help of Toronto-based music historian Kevin Howes. Howes says his collection began as a DJ in the 90s, sharing space with a diverse set of kids whose parents had come from the Caribbean and collecting from local record shops. Howes says that the songs on Jamaica to Toronto were “basically my DJ crates.”

Through his work as a music journalist and historian, Howes connected many of the musicians to Seattle-based label Light in the Attic. For the first time, music by Jamaican-Canadian legends like Jackie Mitoo, Wayne McGhie and Bob and Wisdom was widely available. “It was more a case of helping to make incredible life-changing music from the analogue era available to people from the digital era, and sharing information about those who made it possible for the artists of today in a time where the support wasn’t there,” Howes said.

With the success of Drake, The Weeknd and the slew of Canadian artists gaining international notoriety, it seems a crucial time for reappraisal of the role of Black musicians in a Canadian context. While we’ve come a long way in terms of celebrating homegrown talent, it appears that labels and the wider music industry are slow to support our own artists.

Dalton Higgins, an academic and publicist, is looking to address that. A new university course taught by Higgins will study the image of artists like Drake and The Weeknd and provide critical academic recognition to their music. Higgins points to the history of Canadian rappers signing to American labels: Michie Mee to First Priority; Maestro Fresh Wes to LMR; and Kardinal Offishall to MCA. “They all signed to American record labels,” he says. “Much of Black Canadian success when it comes to music, it’s because they got support from American record labels.

“It’s not like they’re products of the Canadian music industry, they’re products of getting support from America and abroad,” says Higgins. “I think that’s a bit of a source of embarrassment for Canada. It’s not like Canada has to do with the success of African-Canadian exports who are doing so fantastically well.”

The Weeknd was named Spotify’s most-streamed artist in January, while Drake broke records for most combined streams on the platform last year. “If two of the top 10 streaming artists in the world are from Toronto and happen to be Black and Canadian, is that resonating with the industry here? No, it is not,” Higgins says. Although increasing international recognition might signal a bright future for Black Canadian artists, the change is not coming fast enough. “One would think that booking agencies and record companies would have an a-ha moment and be like ‘holy shit, Black Canadian artists are punching way above their weight,” Higgins says. “Let’s go sign a bunch of artists and try to move mountains, make some magic happen. That’s not happening.”

Higgins says he sees small token gestures of improvement from the Canadian music scene, but it’s not nearly enough to stop the leak of Canadian artists to American labels. His university course, launching in Winter 2022, is one step toward shining a light on Black Canadian contributions to music.

By Megan Magdalena

A sold-out night at the Vogue Theatre brought Warped Tour memories roaring back.

By Stephan Boissonneault

With There Is Nothing In The Dark That Isn’t There In The Light, the veteran vocalist leans into intimate, searching folk.

By Sam Hendriks

A refined turn toward clarity reveals Melody Prochet at her most grounded and assured.