Nosferatu is a Masterclass in Atmosphere

Robert Eggers’ bigger and bolder reimagining may not be the definitive iteration, but it offers the most enveloping.

Directed by Robert Eggers

by Prabhjot Bains

- Published on

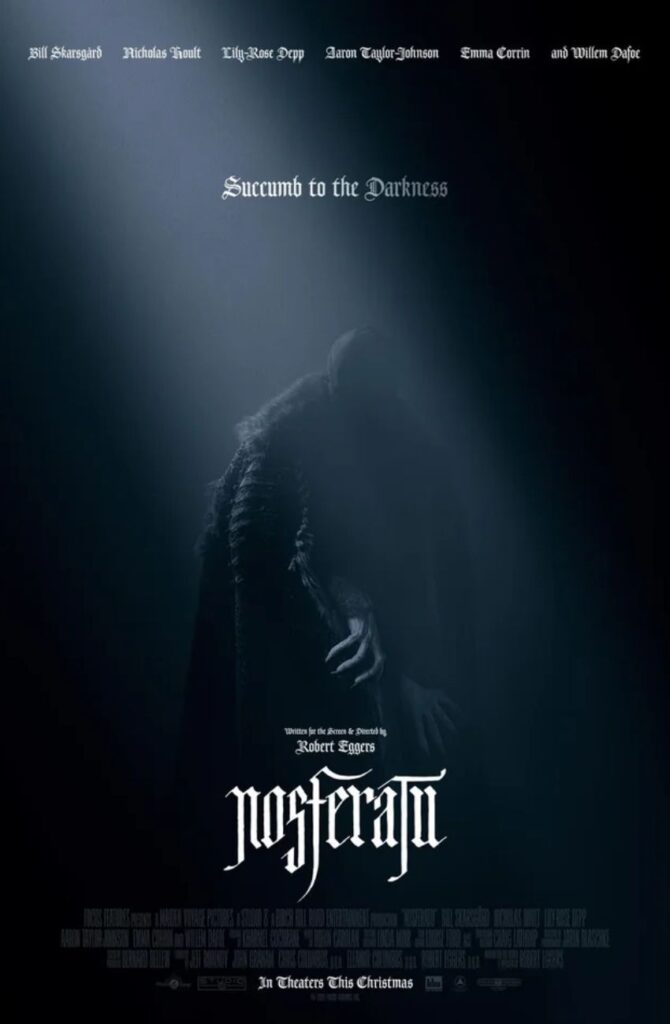

For a third time, Nosferatu’s all-consuming Count Orlok is woken from his slumber and made to haunt the silver screen. Yet, the question remains: Is writer-director Robert Eggers justified in waking the beast after all these years? Audiences don’t so much arrive at the answer as they are naturally drawn to it, by the seductive, epic canvas on which this gothic horror is gracefully splattered upon. Building off F.W Murnau’s silent classic (Which unofficially adapted Bram Stoker’s“Dracula”) and Werner Herzog’s excellent 1979 remake, Eggers’ bigger and bolder reimagining may not be the definitive iteration, but it offers the most enveloping. Eggers’ Nosferatu is a pure masterclass in atmosphere that beckons audiences to absorb every detail and crevice of each frame until they are made as lost and horrified as the characters on screen.

Set in the fictional German port city of Wisborg in 1838, Nosferatu centres on devoted newlyweds Thomas (Nicholas Hoult) and Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp, who impressively takes the form of a possessed contortionist) Hutter. For much of her adolescence, Ellen endured night terrors brought on by what she believed was a spirit or creature that latched onto her. The care and company of her husband subsides these visions, but not for long.

At the behest of the real estate company he works for, Thomas travels to Transylvania to purchase a crumbling castle belonging to a Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård). What begins as a chance to improve his budding family’s fortunes quickly turns sinister, as Thomas, his wife, and soon all Wisborg fall prey to the Beast’s yoke.

This version of Nosferatu quickly casts a spell over audiences with its dusty, detailed production design and sumptuously stark cinematography. From enrapturing vistas and mountainscapes to imposing stone corridors, Eggers offers a visual feast that doubles as an immersive dreamlike history lesson—crafting the richest, most transportive 19th-century world in recent memory. Instead of solely drawing on the form and feel of a traditional vampire film, Eggers taps into the fear and doubt Western Europe surely felt during the time of Stoker’s writing—resulting in a film that feels singular in its approach to both the vampire mythos and the zeitgeist that birthed it.

Yet, the true splendour of Nosferatu is felt when Skarsgård’s count takes control. Orlok first occupies the corners of the frame, cloaked in an impenetrable darkness that dares the camera to follow him. His deep, droning, and slow-rolling speech pierces the bone and quakes the screen, slowly conquering the frame to reveal less of a human-like monster but a predatory and festering anthropomorphic carnivore. We rest on each word, which feels like it’s assaulting us from every direction until we too, like Ellen, fall prey to his clutches.

Eggers’s film is as immersive as it is drawn out (exceeding the runtime of its predecessors by a considerable length). Its sheer heft dulls its fangs, as it musters only a skin-deep examination of female desire and sexuality amid a puritanical society. While these shortcomings keep Nosferatu from emphatically claiming its place atop the vampire pantheon, Eggers crafts a film that would be lesser without it.