Protomartyr Dig Themselves out of the Desert

The future is bleak, until it isn't.

By Gregory Adams

Photos by Trevor Naud

- Published on

By the time Casey hit his 40s, he found himself cradling a baseball bat signed by 00s era Tigers slugger Dmitri Young, a knot twisting in the singer’s stomach as he wondered whether his family home was about to be broken into for the fifth time in two weeks. This less-celebratory moment is re-lived through the record’s “We Know the Rats,” where Casey’s weary baritone intones the dread of home invasion, but also ponders, as he explains to RANGE, “the systems that would cause somebody to feel like they needed to steal to survive”.

Even beyond these baseball-related memories on both ends of the emotional spectrum, Protomartyr contemplates extremes throughout Formal Growth in the Desert: life and death; joy and pain; arid landscapes and lush vegetation. Notably, the group — Casey, guitarist Greg Ahee, bassist Scott Davidson, and drummer Alex Leonard — travelled down to Tornillo, TX’s famed Sonic Ranch studio to record. Casey confesses, however, that they didn’t really sightsee much during the sessions. The desert, instead, existed inside the band.

“A desert [is] an empty place without life, is basically what I’m going for,” he explains of the allusion, relating this in part to how Protomartyr had languished when their previous album, 2020’s Ultimate Success Today, dropped a few months into the pandemic — making the group naturally unable to tour at the time. Casey does point out that he’s been singing about barren landscapes since “In My Sphere,” the first song on the band’s 2012 debut full-length, No Passion All Technique, but all the same, things were looking bleak during the early, inactive days of COVID. “[The desert] was definitely the band’s mental state during quarantine, [but the album is about] getting out of that hole we were all in, and finding some growth beyond that,” he says.

Protomartyr’s music can be overwhelmingly beautiful, as the raw edges of Casey’s florid rasp careen off Ahee’s aching, distortion-blown melodies and the powerfully cyclical slam of the rhythm section. That’s still the case with Formal Growth in the Desert, but this time around Ahee wanted to augment the arrangements with weeping pedal steel — an instrument he doesn’t know how to play, mind you. Some songs had already been worked out on the road by late 2021 — others in a friend’s cabin in Upstate New York — with the slide-based instrument existing only in the theoretical. By the time the group made it south to Sonic Ranch in 2022, they lucked into meeting session musician William Radcliffe, “a local fella that referred to himself as the second-best pedal-steel player in El Paso.” (“Where’s the best one?” Casey adds with a laugh of the designation).

Though Casey notes that they “wanted to make sure it didn’t turn into Protomartyr’s country and western record”, Radcliffe’s sliding on the album anchors pieces like “Elevation Dances” and “Polacrilex Kid,” updating Protomartyr’s songbook with a unique melancholy. Ahee’s songwriting can similarly land mournfully, the guitarist perhaps in tune with the grief Casey was going through following his mother’s death after a long battle with Alzheimer’s.

“It was very sad, but it was also a relief that her suffering was over. We had 10 years to mourn this tragic situation, but I was worried,” he explains. “When my dad died [from a sudden heart attack], I went through many years of being morbidly depressed about things. I was worried that was going to happen again.”

Album centrepiece “Graft vs Host” reflects on the death. It’s understandably grief-stricken, the singer describing his mood as the darkest possible depths of a non-reflective vantablack colour. But as the song unfolds, Casey thinks of his mother’s caring spirit and pledges to push on with a positive outlook (“She’d want me to try and find happiness in a cloudless sky,” he sings determinedly). “I’m not a happy person, or a very upbeat person, in general,” the Protomartyr frontman reveals, adding of an imagined, in-song procedure, “I’ve got to inject this hopefulness in me after this tragedy and hope that it works. And if it doesn’t…that’s going to be a bad thing.”

The act of moving on is also conjured through “We Know the Rats.” Outside of a couple years of college, Casey had lived in his family’s Detroit-area home his whole life. The singer’s fiancée was due to move in, too, but a rush of break-ins left the frontman feeling unsafe.; the house was also starting to wear its age. So, Casey learned to let go. The house was sold to family friends on the block; Casey’s brother, in turn, sold the singer his nearby home, since he’d just bought a farm outside of Detroit.

“I was keeping the house almost exactly the way my mom and dad left it. It was falling into disarray, because 60 years of junk had [accumulated] there. Precious things to us, but [still]…” Casey says, adding of his move, “This [was] probably a good thing, because I would have sat in a falling-apart old house until it fell down on top of me. I was the keeper of a museum that nobody wanted to visit. It was a relief to have my hand forced.”

The emotional arc of Formal Growth in the Desert is wide, running from the emptiness felt after losing a parent, towards moments of self-doubt, and onto the embracing of hope. At one extreme, Casey caps “Polacrilex Kid” with an existentially troubling mantra of “can you hate yourself and still deserve love?” The album ends, however, with a calming, supportive kiss.

Casey notes that the finale, “Rain Garden,” is Protomartyr’s first explicit love song. It’s a veritable oasis at the end of Desert. It took not just a whole album to get here, but Protomartyr’s entire existence. The band are due to tour behind their latest triumph, while Casey and his fiancée are eyeing a wedding date. After a few particularly brutal years, Casey’s welcoming the change of pace.

“I am getting married,” he offers of how the elevated mood of “Rain Garden” resonates with him. “It’d be fake and cliché if I just ignored that my life had drastically changed and continued to write a certain type of Protomartyr where I’m like, ‘Life sucks; there’s no point to living.’ My life doesn’t represent that! It becomes comical [otherwise]; you start sounding like a depressed Dracula if you’re always moaning-and-groaning about the evils of society. Like, I can write 20 albums about the evils of society — that’s never going to stop — but you have to find new ways to [express yourself]. You have to have the love song to throw the other feelings into relief.”

By Sebastian Buzzalino

Calgary’s beloved summer festival trudges through the downpour with a stacked lineup of genre-bending greatness.

By Megan Magdalena

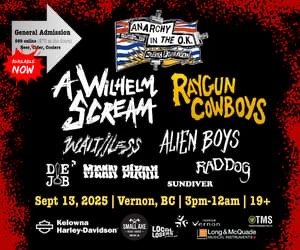

Rebecca White of Vancouver punk act WAIT//LESS interviews frontwoman Missy Dabice in a backstage catharsis session.