By Fraser Hamilton

The British singer mixes confessional lyrics with pop-rock hooks, making catharsis and self-sabotage sound like a party.

For the first time, Pussy Riot’s oeuvre has been assembled into a retrospective, Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot’s Russia. The exhibition, which has already been shown in Montreal, will grace North Vancouver’s Polygon Gallery this spring. Collected and presented by founding member Maria Alyokhina, it surveys the past 13 years of the collective’s revolutionary actions and subsequent institutional responses, including Alyokhina’s two-year prison sentence for “organised hooliganism” and her more recent house arrest, contextualised with the piecemeal path that’s led to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Alyokhina, who was working on her second novel when she caught up with us from Reykjavik, also composed the exhibition’s accompanying text, while co-curator Ragnar Kjartansson brings the chronology to life with illustrations. Kjartansson first urged Alyokhina to showcase Pussy Riot’s public disruptions in this form when she shared her archive with him in 2021. Though many of their performance pieces achieved viral success, most never reached a global audience. Hindered by Russia’s apparatus of suppression, misinformation, and surveillance, it felt imperative to present their work as widely as possible.

“It’s really true that people didn’t know a lot of the things which we are showing to them,” Alyokhina tells RANGE. “And not only actions, they didn’t know what was going on in Russia. They hardly remember the annexation of Crimea. They’ve seen just fresh footage from this war, and they don’t have a whole picture about how the country was living all this time and what they were doing with us, with all of us, who are against the regime.”

“And I think this road to hell is very important to articulate because I don’t think that Russia is something special,” she continues. “I think if people lose democracy, they are losing it part by part. And it can happen anywhere if people stop fighting for their rights. I hope that people who see what they were doing with us will open their eyes and it will make a change.”

Riot Days performance. (Photo: Pussy Riot)

Alyokhina explains Russia has remained the same since the collapse of the Soviet Union — Putin considers himself the “new Stalin” carrying over the existing network of repression and, as she knows from personal experience, modern prisons are a “copy of the gulag system.” However in the years since Pussy Riot’s first interventions, her home country has rapidly escalated from a “classical authoritarian state” to the type of totalitarian nation that “occupies the territories of other countries.” But to grasp this latest evolution in Russia’s geopolitics, “it’s important to understand its roots,” she says. Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot’s Russia delves into this history with the flair that defines their art.

Alyokhina’s play RIOT DAYS, a hybrid concert, visual art and spoken word piece based on her time in prison, rounds out the exhibition. She performs alongside electro-violinist Alina Petrova and two Pussy Riot activists, Olga Borisova and Diana Burkot, who took part in the infamous 2012 demonstration at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour but managed to evade arrest. Alyokhina hopes audience members who catch the performance “can take a part of our riot with them.”

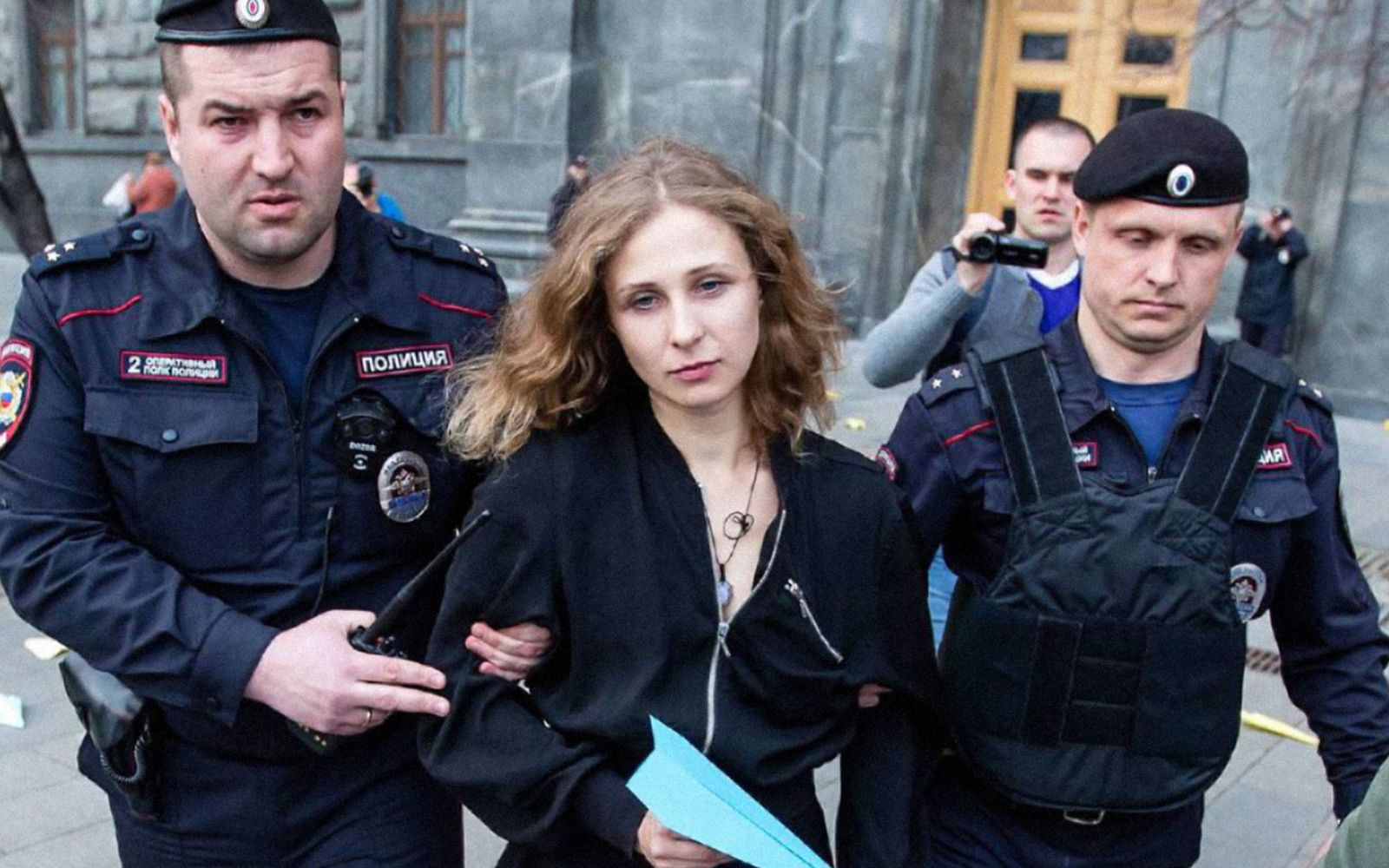

Maria Alyokhina arrested after the action ‘Paper Planes,’ 2018. (Photo: Martin_camera)

Collectivity, after all, is one of the key lessons Alyokhina has learned after decades of boots-on-the-ground activism. What else has been essential to Pussy Riot’s success? “Read the news and react,” she says, explaining that politics “is not something for men in suits, it’s for everyone and it’s about everyone.”

When it comes to following in Pussy Riot’s footsteps, Alyokhina says there isn’t a universal recipe. What matters most is getting out there without overthinking things. “Even if you make a mistake, it will be your mistake. No one did it before. It will be yours. And it will teach you.” Her collective never imagined their unpolished punk music and rough-around-the-edges rebellion would become a phenomenon. “I want to address my message to girls,” she concludes. “Don’t be afraid. Do your thing.”

Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot’s Russia runs at the Polygon Gallery until June 9, 2024

By Fraser Hamilton

The British singer mixes confessional lyrics with pop-rock hooks, making catharsis and self-sabotage sound like a party.

By Hannah Harlacher

The Juno-nominated artist stretches beyond folk minimalism without losing the intimacy that made them a generational voice.

By Adriel Smiley

The Canadian country star follows up his Gold-certified debut with a heartfelt collection three years in the making.