By Stephan Boissonneault

With There Is Nothing In The Dark That Isn’t There In The Light, the veteran vocalist leans into intimate, searching folk.

Showing such expertise is a far cry from the young artist who once claimed he didn’t know much about Prairie rap, even though he was mired in it as an independent artist at the time. “It wasn’t a thing where it was on TV or something,” says Pemberton over Zoom from Toronto where he currently resides.

Showing such expertise is a far cry from the young artist who once claimed he didn’t know much about Prairie rap, even though he was mired in it as an independent artist at the time. “It wasn’t a thing where it was on TV or something,” says Pemberton over Zoom from Toronto where he currently resides.

He recalls seeing artists from Peanuts & Corn, a Manitoba-born record label, performing in his hometown of Edmonton. “That really blew me away because I was like ‘Oh, these are people who are rapping about stuff that I can relate to, and I didn’t even know that existed,” says Pemberton. “The entire idea of wanting to be a rapper coming from Edmonton was just unheard of.”

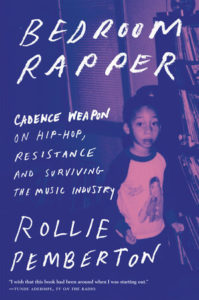

Despite not having a blueprint for success from his local surroundings, Pemberton’s early work as Cadence Weapon earned him laudations and got him closer to his goal of becoming a superstar. His crown jewel moment? Playing Lollapalooza the same year as Kanye West, Radiohead and Rage Against the Machine. “Being on the same stage as Saul Williams and all these big artists. That was really big for me. That was a moment where I was like, ‘Okay, yeah, it’s getting real.”

But for what it’s worth, the success keeps rolling in. It’s safe to say he now knows a thing or two. RANGE sat down with Pemberton to hear his tales about making a living as a musician and making sense of the chaos of the music industry.

For all of the US and Canadian touchpoints in Pemberton’s music, there’s one scene that repeatedly threads through his music. UK grime, two-step and garage music form a foundational element to Cadence Weapon’s sound. Pemberton says his appreciation for the distant scene is based on his research on the Internet. Many early excerpts of Bedroom Rapper reveal a nerd who obsessively communed with the fellow rap fanatics on nascent hip-hop forums and listened intently to radio rips from distant lands.

“I was really early into grime. I was listening to a lot of RINSE FM radio rips,” Pemberton recalls. “Something about the quality of it…it felt like it was being beamed in from another planet, it felt so otherworldly. This actually sounds like the future.”

The UK-oriented sounds became a thread he would use in his own work. Take “On Me,” from his Polaris Prize-winning album Parallel World, as an example. The track’s introduction comes equipped with a melody of synths that could convincingly mirror a JME or Skepta beat. A feature from London-based grime legend Manga Saint Hilare seals the deal. “I do feel like I’ve really found my own sound where it’s definitely electronic, definitely Black, but it’s coming from a different perspective than anyone else would,” he says.

Pemberton hasn’t only found success as a rapper. His critical essays and reviews have found a home in publications like Hazlitt, the Guardian, and Pitchfork. His combined work as a critic, creative, and consumer give him a unique viewpoint into how music is received—with rabid praise or immediate scorn in the era of social media.

“This is my problem with the way people listen to rap now. There’s no room for nuance at all, or subtlety. Especially when it comes to Twitter.” He cites Kendrick Lamar’s polarizing Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers as a recent example. “An album comes out at midnight, and then at 12:05, people are like it’s trash or it’s classic. How could you possibly know? You don’t know. You don’t know how you felt an hour ago, about anything. Were you hungry? Do you remember? People don’t fucking know!”

The knee-jerk reaction is a frustrating point of contention as a creator and a rap evangelist. Pemberton says Lamar’s music, as well as his own and that of his peers, should be consumed with an air of timelessness. It grows, it changes, it responds to listeners’ perception over time.

“He’s coming from a perspective of ‘don’t listen to right now, and only for right now,’” he says. “This is something like that you can live with and learn from it and really deconstruct it for months or years. You know, we’re trying to make some substantial music here.”

The amount of success Pemberton has garnered has put him face-to-face with his idols. He recalls meeting De La Soul producer Prince Paul. Pemberton is enough of a diehard rap fan to adorn himself with a tattoo of the classic De La Soul album Stakes Is High. Although the project was notably De La Soul’s first album to not be produced by Prince Paul, it didn’t stop Pemberton from excitedly showing off his ink to his disinterested hero after a festival performance. “I think he was freaked out, but I also think it was a little weird because he didn’t produce that album. He’s like ‘why are you showing me this, man? I hate this fucking album.’”

Pemberton never got another chance to redeem himself, which reminded him of the age-old adage: never meet your heroes. In fact, Pemberton says hasn’t had any particularly nice experiences with any of the alternative rappers whose blueprint he followed, but he’s sympathetic to the anxieties that come with that level of celebrity. In short, the life of an artist becomes just a job. “What is amazing to other people just becomes routine to you.”

It’s a lesson learned for someone as bubbly as Pemberton, who, by his own admission, is way too open with his desire to get a picture and to interact with artists as friends. “I love getting into opportunities where I get to talk to other artists and share music with them,” he says. “That’s one of my favourite things about being an artist; being able to bounce ideas off of somebody else who does it, you know? And, yes, the key is just to keep it normal and remember that they’re human.”

Although times have changed since Pemberton was an attic-dwelling hip-hop head scouring forums for beats, the status of the bedroom rapper has not. While the archetype of the SoundCloud rapper is the perennial butt of jokes, the snickering often subsides when they achieve the coveted label of celebrity, usually with one viral track.

Think of Juice WRLD or Lil Nas X, whose first tunes were lauded on social media before they were critically acclaimed by the masses. In today’s climate, Pemberton’s advice for the kids in their makeshift studios is to fill an unexplored niche.

“I would say try and be original, try and do something that you haven’t heard before. Don’t try to imitate somebody else. And do as much research as you can.” As he says in the book, his whole career is predicated on research, but he doesn’t see the same fervour from his peers.

“I feel like there’s not as much of an interest in learning about the history of rap,” he says. “You don’t need it, I’m not saying everyone needs to do this to make music, but the more I learned about the canon of hip-hop, and the more I learned about the existing records, it helped me subvert what was there.”

By Stephan Boissonneault

With There Is Nothing In The Dark That Isn’t There In The Light, the veteran vocalist leans into intimate, searching folk.

By Sam Hendriks

A refined turn toward clarity reveals Melody Prochet at her most grounded and assured.

By Judynn Valcin

Inside the Montréal musician’s shift toward ease, openness, and a sound that refuses to collapse even as it teeters.