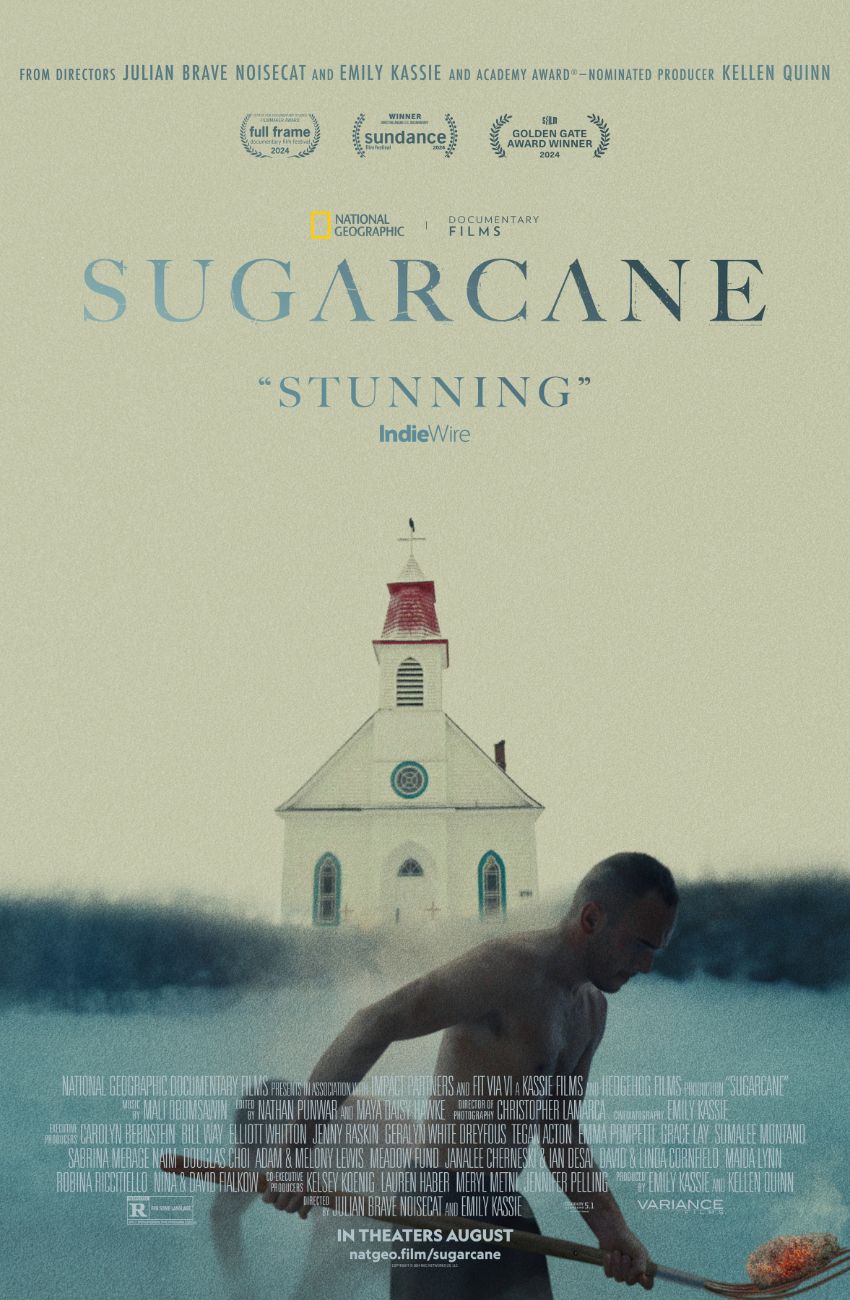

Sugarcane: How a Documentary Helped a Community Heal

Co-directors Julian Brave NoiseCat and Emily Kassie found making their film about a B.C. residential school restorative unto itself.

by Maggie McPhee

- Published on

The last residential school in Canada closed in 1997. For more than 160 years, these church-run institutions separated Indigenous children from their families to “kill the Indian and save the man” through forced assimilation and ethnocide. Though these were horrific sites dominated by abuse and neglect, Canadians have long denied such allegations. Until the summer of 2021, when an unmarked grave of 215 children was discovered on the old grounds of a Kamloops residential school, and the truth could no longer be overlooked.

As Nations across the country conducted searches, filmmakers Julian Brave NoiseCat and Emily Kassie joined Chief Willie Sellars and the Williams Lake First Nation to formally investigate St. Joseph’s Mission, a residential school outside the Sugarcane reservation in British Columbia with rumours of misconduct. Noisecat, a member of Williams Lake First Nation, knew all too well what the investigation might uncover. His father, Ed Archie Noisecat, was born on the school’s premises. Priests who worked at these institutions committed widespread sexual assault against male and female students. And at St. Joseph’s Mission, they incinerated unwanted babies. Ed NoiseCat, found in a dumpster as a newborn, is the only known survivor.

The co-directors handle this heavy subject with a delicate hand in their new documentary Sugarcane. The subtle craft of their filmmaking puts pedantry aside, saving space for difficult emotions to breathe. These schools passed invisible wounds down across generations, and trauma can make opening up next to impossible. As Sugarcane unfolds, its participants unearth not only the facts of their history, but the suppressed suffering that has festered below the surface. Julian and his father weave one narrative thread as they grapple with the past and its consequences on their strained relationship. Many of the film’s subjects share a similar trajectory of trial and triumph, steadily shedding the shame that has weighed on them so long.

“A camera in the right hands can be an incredibly transformative tool,”NoiseCat tells RANGE. “The camera tells people that they matter, that their stories matter. It calls them to live their life and to be the version of themselves that they want to be seen as through the story. When facing circumstances like we do with this genocide, that nobody talks about even in our own community, in our own family, that was a really powerful thing.”

“For many of our participants, the camera gave them agency, it told them that they deserve to be heard,” agrees Kassie. “We were all serving this bigger thing and to be a part of something like that, to feel mission driven, to feel like something was unfolding that was drawing us all to it, and to come together as a team to serve it was really extraordinary.”

St. Joseph’s Mission Indian Residential School in summer. (Credit: Sugarcane Film LLC)

Making a film can be a way of building community. Even when addressing an atrocity like the residential school system, Sugarcane’s crew and participants felt the healing power of banding together. Colonialism sought to fracture Indigenous solidarity, but every new bond formed — whether through the structure of a documentary, the unity of an investigation, or the vulnerability of sharing one’s story — patches up those cracks. “Part of the incredible joy of this experience,” says NoiseCat, “is the love and camaraderie not just between me and my dad and the people on camera but also the love between the people behind the camera and the people in front of the camera and the love that our team had for each other.”

“It is that very human connection,” he continues, “that connection to who we are, to our relations, to the places that we come from, that remains the thing that is going to help us survive and come out the other side of this incredibly awful history that is still haunting our communities.”

Sugarcane exemplifies recent changes in the Canadian conversation around Indigenous issues, as well as the growth flourishing within First Nations groups. NoiseCat and Kassie, who come from backgrounds in international investigative journalism, hope the film acts as a catalyst to spark dialogue in the United States as well. Both countries share a colonial history, and the residential school system in the U.S. was three times as large, with at least 408 federally funded boarding schools. “It’s imperative that this story is reimagined in the public consciousness as a foundational story of North America,” says Kassie.

“That’s a really significant part of our history that we are just starting to reckon with,” adds NoiseCat. “It’s part of my own family’s story and it’s something that we still to this day struggle to talk about. I think that it’s really important that the truth part of Truth and Reconciliation does not get hopped, skipped, and jumped over so that we can get to the nice part, which is reconciliation.”

By Glenn Alderson

A deep-listening session reveals how Apple Music’s sonic innovation reshapes the way we hear.

By Cam Delisle

Dominic Weintraub and Hugo Williams take audiences on a treadmill-fueled ride through the chaos and hope of modern life.