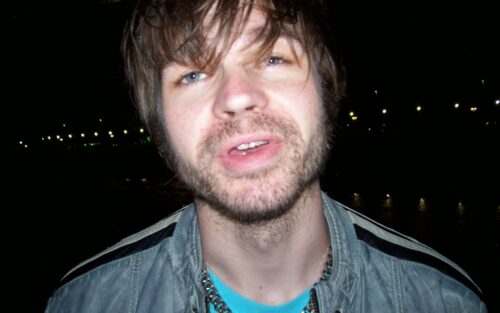

In Search of Realization, with Michael Gira

The Swans “impresario” speaks about seeking understanding, the unsure future, and his collective’s last obelisk.

By Khagan Aslanov

- Published on

Even then, in his proverbial nascence, there was something different about Gira’s vision. Bands like Mars, Theoretical Girls, and Sonic Youth were pushing guitar noise to its very brink, seeing what morphologies could be recovered from the process of wreckage. It sounded scrappy, and boundless and raw, but Gira was already shaping monsters. Early Swans material was built out of clanging industrial noise that sounded like dying machines. It was loud and lonely and appalling, and moved relentlessly forward. They were one of the only bands from the no wave scene to survive in their purest form, and as Sonic Youth ascended to the mainstream and beyond, Gira seemingly burrowed Swans deeper and deeper underground, building an insular world for the ever-changing collective to work towards their pursuit of obliteration. Even as their music grew softer and more patient, it remained a halting, misanthropic presence. Then, in 1996, after touring their critically-acclaimed drone and audio collage-inspired Soundtracks for the Blind, Gira disbanded Swans.

In the ensuing years, Gira turned his attention to Angels of Light, a folk project that abandoned the harsh noise of Swans in favour of countrified, hyper-melodic arrangements. It also allowed him to devote himself to his primary instrument and one that he still uses to craft songs, the acoustic guitar. The story goes that at one of his shows, Gira had a sudden realization that the immense emotion that the music he was writing carried urgently needed a similarly immense sound to become true. And so, in 2010, just as unceremoniously as he had ended them, Gira brought Swans back to life.

“I was happy to do Angels of Light, but it didn’t do much in terms of reaching people,” he says, explaining that the resurrected Swans, if nothing else, was a way to connect his music to listeners on a more visceral level.

Again, this newfound work was different. Gira was no longer warping from the outside in. The reawakened Swans were now building enormous outward spires of sound, shaping colossal albums that sounded as imposingly finite as they were irresolute. It was still misanthropic and appalling in its own way, but Gira was grasping for something larger, more transcendent. Big open chords and gospelled progressions were finding their way into his droning, heavy arrangements. By then, the collective, still endlessly morphing, was a critical darling, which allowed Gira to take his new vision across the world and back.

All of this leads us to Birthing, the returned Swans’ seventh LP, and according to Gira, the last monolith he will build.

“I just don’t want to continue relying on the overwhelming areas of sound I’ve used in the past. I want to find a way forward,” he says in response to ideas of potentially re-enacting a past, less imposing embodiment of Swans or returning to Angels of Light. “I’m not really sure what’s going to happen.”

As our conversation progresses, it’s fascinating to get even a cursory glimpse into the inner workings of a group of artists who have created such far-reaching works. For example, given how engrossing and nuanced Swans’ music is nowadays, the band does little in terms of culling material. “I have trouble being productive. Once I write a song, it becomes gold to me, and I hate not using it,” Gira says, laughing. “So we use them and try to give them the best world they can have.”

Of course, these compositions are allowed to take on endless tiers of transmutation on the road, and Swans’ live performances have long been something to behold. By turns simmering and explosive, they seem designed to evoke a big emotional response from the audience. In some way, the personal process Gira himself goes through as these albums come into existence mirrors their projections as something all-consuming.

“What happens is I finish the album, and then I listen to it obsessively, and then it’s completely drained of blood, and sounds like nothing to me,” he says. “And then, indeed, I am empty, and I have to find a way to move forward.”

Whether it’s true or simply imposed by the album’s name or the listener’s perception, there is something in Birthing that suggests a new life is underway. Still as gargantuan and hungry as its predecessors, it has a shimmering, ascendant quality, and on repeat listens, sounds more and more like a giant exhale.

“I have tried to be true. One of my strengths has always been dealing with failure. I usually find at the end of an album that I have successfully deluded myself, and that I’m just a fucking phony. So I have to start again,” Gira says, and then laughs again at the ensuing silence from my part.

This is Michael Gira today. He no longer pursues obliteration, but realization, a continuous way forward. Tantalizingly, he says that he’s not sure if the new songs will even figure on live setlists, and then casually mentions that he already has “three and a half” songs written for whatever Swans do next:

“I don’t know if I am ever satisfied. But I do know I will continue making music as Swans.”

By Stephan Boissonneault

Nate Amos revisits a decade of stray ideas and turns them into his most compelling record yet.

By Khagan Aslanov

Mike Wallace’s electro-punk project premieres the hypnotic, percussion-driven video for "Certain Days."