The Brutalist: Inside Brady Corbet’s New Great American Epic

The director discusses the striking parallels between architecture and filmmaking, the power imbalances that plague art, and not giving a fuck.

by Prabhjot Bains

- Published on

During the first act of The Brutalist, protagonist László Toth (Adrien Brody), a Jewish-Hungarian Holocaust survivor who arrives in America in the wake of the Second World War, is asked why he chose architecture as his trade. He responds: “Nothing is of its own explanation. Is there a better description of a cube than its construction?” It’s a pointed and poignant statement that encapsulates director Brady Corbet’s own meticulous and exacting vision. “Of course, I feel the same way about my films,” Corbet tells RANGE, “If you could tell a film, then why make a film?”

Shot in 70mm with the largely obsolete VistaVision format and running a mammoth 216 minutes—including a built-in intermission and overture—The Brutalist unfolds as a grand American epic that’s not only grounded in the past, but thematically attuned to the present.

In a story co-penned by his longtime partner Mona Fastvold, the Bauhaus-trained Toth—who Corbet notes is an amalgamation of real-life architects Marcel Breuer, Paul Rudolph, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and László Moholy-Nagy, to name a few—arrives in Ellis Island with little to his name. He’s separated from his wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), who remains in a ravaged Budapest with his niece Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy).

He settles in Philadelphia and works at a furniture store owned by his cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola), where he runs into wealthy industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce) during a surprise home renovation. Impressed by his skills and knack for intellectually stimulating discourse, Van Buren recruits Toth for a colossal new project, resurrecting a dream he thought was lost to war and time—but it soon costs him everything to realize.

Corbet’s film is so individual in design and approach that, much like an architectural feat, it boldly juts out into the cinematic landscape, awing and inspiring from every angle. The analogy is not lost on Corbet, as he allows form, feel, and style to pervade in a film whose very construction informs its weighty meditation on art, capitalism, and the American Dream.

“In the Venn diagram, I think that there’s a lot of overlap between architecture and making a movie,” Corbet notes. “It comes from a place of obsession. It comes from a place of real stubbornness. I never start something that I don’t finish. But that’s, of course, a blessing and a curse.” It’s no coincidence that the 70mm film stock feels as heavy as the concrete Toth fascinates and obsesses over, as The Brutalist towers over audiences as an inscrutable behemoth, rich in allegory and metaphor that consistently folds in on itself.

For Corbet, the film is “primarily about post-traumatic stress and the way that post-war architecture and post-war psychology are intrinsically linked.” He continues, “I’m constantly thinking about the defining events of an epoch. All of my films are virtual histories, and they’re concerned primarily with American culpability.”

Yet, what makes The Brutalist such a fascinating piece of historical fiction is that it forgoes the traditional lens with which they are often made. “I think that I struggle a lot with biographies and with most biopics because they often represent history as being something linear,” Corbet says. “It’s a series of dates and figures. It’s cause and effect, cause and effect, whereas I think I’m more interested in a sort of ambient tyranny. What’s in the air, what’s in the water, what’s in the atmosphere that is all contributing to these defining historical events and happenings.” In this way, the experiences viewers bring to The Brutalist are rendered materials as part of its grand design.

This historical aether gives way to a greater conversation around the strained relationship between art, commerce, and class. Much like how the downtrodden Toth struggles to ply his trade in a foreign land, filmmakers are often at the mercy of studios and investors that limit the reach, merit, and worth of their vision. “Filmmakers are frequently exploited… they are treated as if it’s a privilege to be able to make your film, and so frequently the powers that be lean on the filmmaker who’s so desperate to get their project off the ground that they’re willing to do it for free,” Corbet says. “You’d be surprised how many people are currently campaigning their movie for Best Picture that can’t pay their rent.”

For Corbet, art isn’t a privilege, but a grave necessity. “I certainly don’t want to read a book that was written by 24 executives, so I think that a singular vision is something that we should encourage and foster,” he says. “In fact, everyone should be beating on a drum for the director’s cut of absolutely every film, because even if a film is imperfect, there’s a consistency and continuity of vision that will always make for a better film, otherwise it ends up looking something like an exquisite corpse.”

The struggle to maintain that artistic vision and integrity sits at the heart of The Brutalist and the long, tiring journey to realize it—which consisted of many seven-day work weeks and 20-hour days. Corbet notes that even the film’s sexual content was a point of contention. “The film was finally rated R, but it was on the bubble for an NC-17 and I just think it’s preposterous,” Corbet says “This puritanism, I don’t know where it comes from. It’s 2024, for Christ’s sake, so I find it odd to condemn the human body.”

“You walk around a museum and everyone’s fucking in every single painting… this movie is about a character that is trying to reclaim his body of work and his body,” Corbet continues. “In the first 10 minutes we understand that [Toth] is impotent following the war and even when he and his wife reconnect, it takes them a long time to physically reconnect.” In exploring these themes frankly, The Brutalist not only becomes an exercise in scope but also in intimate intensity.

For Corbet, “It’s very important to portray survivors that are trying to reclaim their bodies for themselves again.” He adds “It didn’t even occur to me that this film might get an NC-17, and I’m very glad that finally it didn’t, because I never would have changed anything anyway. I don’t give a fuck.”

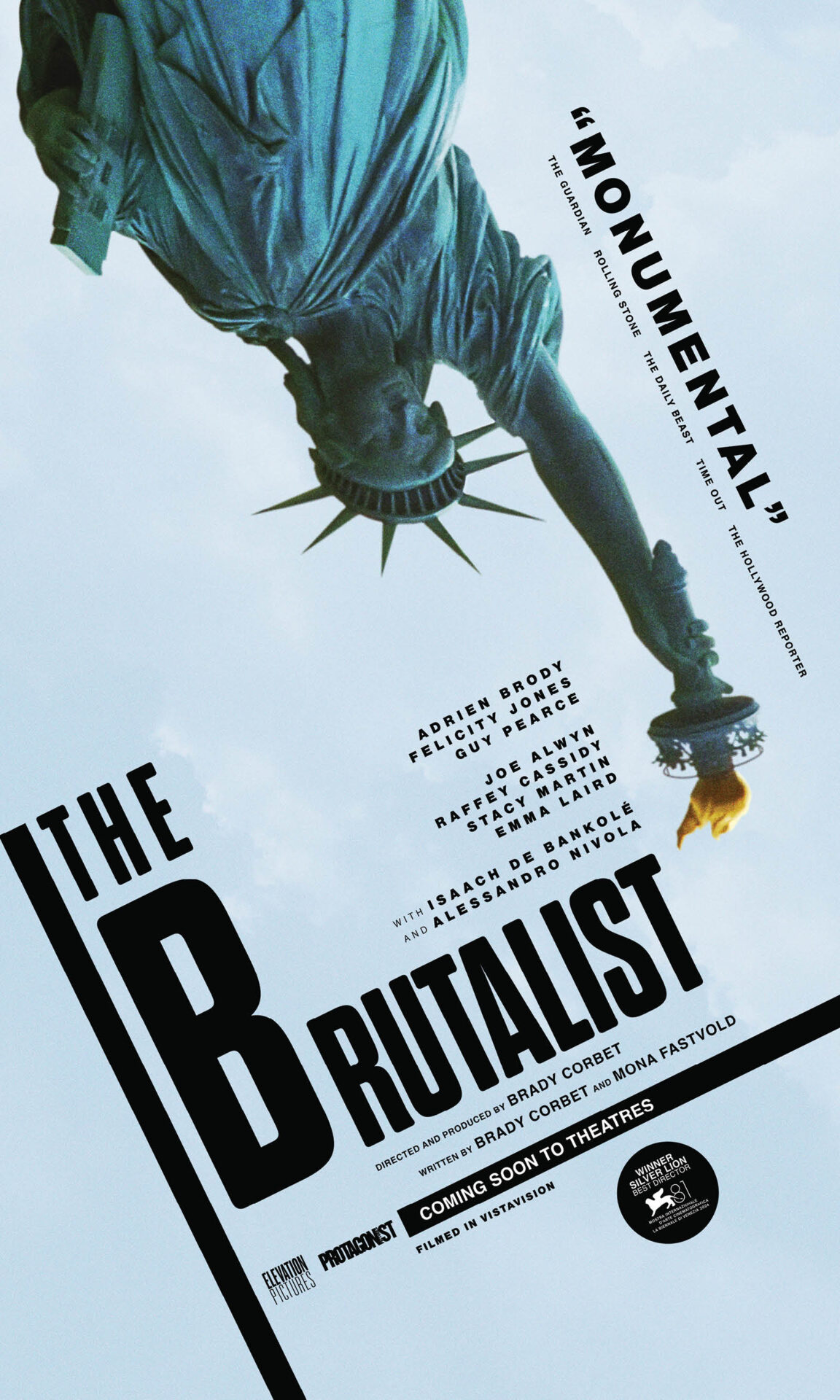

The Brutalist’s greatest achievement lies in its tragic deconstruction of the American Dream—a staggering feat it achieves in an early unbroken shot that takes us through the bowels of a ship to, finally, an inverted Statue of Liberty, flipping the famous call for “huddled masses” on its head and illuminating the envy, pride, and racism that keeps privilege in the hands of a select few. It’s a truth that reverberates across the film’s lengthy runtime and, for Corbet, works to remind us that “the artistic experience and the immigrant experience have a lot in common, because an immigrant is fighting for their right to exist, and an artist is fighting for the right for their project to exist.”

Despite all odds, The Brutalist survives as precisely the film Corbet first envisioned seven years ago. “It’s exactly the same. There’s not a single scene that didn’t end up in the film, there’s not even a shot that didn’t end up in the film,” Corbet says. “The film is really the screenplay just executed.” In a world that often crushes the dreams of men and artists like Toth, the existence of his story is a testament to their enduring spirit. Corbet’s film is the rare epic that not only burrows into the stark soul of its American epoch, but also distills the limitless potential of its medium. But Corbet’s aims are much more modest: “Just being a part of the conversation, in all seriousness, is actually what matters,” he notes. “If the film performs okay then it means that more movies like this get made.”

The Brutalist is in theatres Dec 25

By Glenn Alderson

A deep-listening session reveals how Apple Music’s sonic innovation reshapes the way we hear.

By Cam Delisle

Dominic Weintraub and Hugo Williams take audiences on a treadmill-fueled ride through the chaos and hope of modern life.