The Weather Station's Gentle Indie Folk Softens the Blow of Climate Anxiety

Familiar themes reappear in gentler form on songwriter Tamara Lindeman's follow up to 2021’s Ignorance.

By Daniel McIntosh

Photo by Brendan Ko

- Published on

The pair are intended to work as companions, but the sonic landscape between the two is a gulf. While Ignorance rode a frenetic wave of staccato percussion and soft disco, Stars forgoes drums entirely. The result is a series of ballads that stand in stark opposition to the previous work. Lindeman says the record exposes an amount of fragility and vulnerability, emotions that “felt like they needed a space.”

The result, however, is no less elegant than its predecessor. Synths ooze and whine, and piano flutters fill the formless space, providing more room for Lindeman’s musings on climate, on colours, on birds. By her pen, the agents of conflict — both personal and universal — are one and the same. The complete lack of percussion evokes a sense of timelessness in the aftermath of Ignorance, like the echo following a scream.

RANGE caught up with Lindeman between stops on the US leg of her world tour to discuss following up her most powerful work to-date, the strangeness of touring, and climate anxiety.

How has it been getting back on the road?

I mean it’s interesting. It’s really different. It’s been a long time since I’ve been touring, essentially other than the tour we did in November. I think we’re all adjusting to how we’ve all changed. The pandemic has changed everyone and changed everything, so it’s strange to be on tour because it’s so familiar and yet I’m wearing a mask everywhere, and I’m not dining indoors. There’s so much different, and the world feels very different, and I feel very different. A lot has changed. Playing shows has been really great.

Have you been interacting with the audience while watching from the stage? Does it feel different in that respect as well?

Yeah. I mean everyone’s wearing masks, so you can’t see their face, and the lack of that sort of facial expression feedback changes your experience. It’s just sort of a feeling of tension, feeling like we shouldn’t be all… It’s going to take a long time to feel safety when a bunch of people are together in a room.

Whereas that used to be a really safe space emotionally. Also, I’m not going to sell merch and talk to people, which is quite different as well. That always meant a lot to me, to have that interaction. Yeah, I’m grateful to still have the music and still have the opportunity to perform at all.

Congratulations on the success of Ignorance. Did the response to it have any bearing on How is It That I Should Look at the Stars?

This record was planned before Ignorance came out, and it was recorded before Ignorance came out, so it hasn’t really impacted it. I think the only thing it changed was it started to make me more and more nervous about putting out this record because I felt like there were a lot of expectations built up by Ignorance. This record is not really going to meet them. That was the one thing that sort of started to impact me, but that’s pretty much it.

In a previous interview you said, “Rhythm was becoming increasingly important as I was touring, I think, because I was playing for larger and larger audiences.” Considering the sonic landscape between the two albums, Stars notably lacks percussion. What was the decision for that?

Well, Stars was just not intended for playing live. You know what I mean? Ignorance was very much a response to that, but then How Is It is just like… I just wanted to make that record, and the lack of drums just felt like the right choice for that music.

I guess you could say too it was a bit of a reaction to Ignorance. I sort of got that out of my system, and then there was just one thing left unexpressed. I think that I never really intended that record or those songs to be out there in the world, in a way, was part of what informed the lack of percussion and the lack of rhythm.

When you say “one thing was left unexpressed,” if you could sum it up, what would it be?

I mean I guess I shouldn’t have said one thing. That’s a bit reductive, but I guess that those songs or that feeling. I mean that piece of the softness. I do think this record feels like an expression of a certain amount of fragility or vulnerability or love so those things felt like they needed a space.

Ignorance dealt a lot with thoughts and reactions to climate anxiety and the climate crisis. Is this something that you think about on the road? I’m just considering the fact that there’s so much you as an individual can’t control in terms of music and travel and carbon footprint. How do you reckon with that when you’re touring?

It’s been complicated. I’ve been feeling a lot of unexpected feelings just being out here, just driving in a big van, gassing up. I’ve been able to lead a very small life in the last couple years, and that’s been really peaceful mentally. I think more than that, just being in the world. We were driving through California and just seeing how the Central Valley just physically looks a lot drier since the last time I was here this time of year. There’s tumbleweeds in the orchard. One of the reservoirs we drove over, the water is so much lower than it should be. We’ve driven through quite a lot of fire-burned areas.

I mean when we were in BC in November, we drove through a storm and missed a bunch of mudslides really narrowly. That was a really intense sort of climate moment. Yeah, I mean I think just the last time I was really out on the road was 2018, and I guess I just feel the change. It’s like I feel the climate changes since that time pretty acutely, especially, yeah, being in the West.

What sort of climate education did you have growing up? Did people discuss concepts like this?

Well, I’m a child of the 80s, so I definitely was told about climate change very young, which I think is kind of rare. I definitely was 100% aware of it as a very small child, and it really terrified me.

It was a very deep fear. It just kind of hit me really hard. I was probably like five. That was sort of my initial understanding, and definitely just having a wider understanding of Earth Day and ideas like that was all part of my childhood. Then in my early twenties, like everyone else, I watched An Inconvenient Truth. I was sort of a part of that moment in the climate world. I was dating an environmentalist and really trying to do what I could. Then I really just put it aside and didn’t really think about it for many years. Didn’t really pay attention.

That was kind of part of what was so powerful about paying attention and starting to actually read about it in 2018, 2019 is I realized how totally out of date all of my understandings were, which I think is really common, right? A lot of people are out of date because they keep changing so fast. For example, this emphasis on individual carbon footprint or just change your light bulbs and everything will be fine. And in the last two years, I mean it’s like staying up to date on all the legislation that gets opposed and then fails. It’s a lot.

I’m glad you mentioned An Inconvenient Truth. What did you think of the climate film of the moment, Don’t Look Up? Have you seen it?

I have seen it. Yeah, I mean I thought it had flaws, of course. It’s very much about America, but I thought it was a really painfully spot-on satire of… I know a lot of people have criticized it for being almost too broad and over the top, and yet a lot of people who work in climate, a lot of scientists have been speaking of it, being like, “This resonates with my experiences. This is literally what happens to me. I’ve had these experiences.”

Some of them have felt it to the bone. So I think it’s the intent. I think part of the backlash of that film is a discomfort with what it says. Obviously, it’s so far over the top, but, no, I thought it was spot-on. I really appreciated that it delved into some painful feelings, and I cried, but I also laughed. I appreciated that.

You recently tweeted, “It’s considered a fringe viewpoint to feel climate grief and anxiety.” Has the process of developing these albums the response to them been effective in that sense for you?

Yes for sure, it’s really helped me to understand I’m not alone and hearing others express their climate grief and anxiety is absolutely helpful. But I find that those feelings still come up when they come up, having community in it and knowing you’re not alone helps, but it’s not everything.

I think one thing that bothers me about the word ‘anxiety’ is that everyone thinks of it as a bad thing that you should make go away, but being afraid of climate collapse is actually a very rational feeling that shouldn’t be minimized or pushed away.

By Sebastian Buzzalino

Calgary’s beloved summer festival trudges through the downpour with a stacked lineup of genre-bending greatness.

By Megan Magdalena

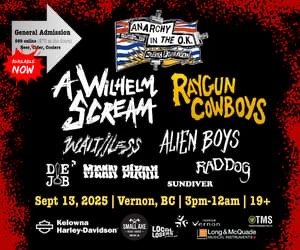

Rebecca White of Vancouver punk act WAIT//LESS interviews frontwoman Missy Dabice in a backstage catharsis session.