The Disaster Movie Canon Develops a Conscience with Twisters

Lee Isaac Chung’s sequel reinvigorates a dormant genre by reminding us of the human and political face of climate catastrophe.

Directed by Lee Isaac Chung

by Prabhjot Bains

- Published on

Jan De Bont’s Twister (1996) was at the forefront of many things. It was among the first crop of Hollywood films released on DVD, it spearheaded the late 90s revival of the disaster movie — preceding efforts like Dante’s Peak (1997), Volcano (1997), the Oscar-winning Titanic (1997), and the more ludicrous Armageddon (1998) — and, above all, it came at a time when our understanding of the climate hadn’t yet become political.

Like the movies that came after it, De Bont’s goofy climate actioner reminded us that no number of monsters could rival the natural terrors of the planet we call home. In releasing to an era that saw “global warming” become “climate change,” Twister and its contemporaries only quadrupled our fear of the weather as a grave danger to human existence. With each subsequent and sillier entry, these films came to embody climate change as both an imminent and distant threat.

Yet, as timely and relevant as Twister was, the film and its many successors often declined to interrogate the role humanity plays in causing and ignoring such climate disasters. De Bont’s film released only six months after the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Second Assessment Report was published, which alarmingly confirmed “the potential for human activities to alter the Earth’s climate to an extent unprecedented in human history.”

While these films weren’t vying to be anything greater than dumb escapist fare (Twister is often heralded as a great “bad movie”), it’s surprising that none turn the lens back on the very people fighting to escape the storm, exploring the hand we play in exacerbating climate change and why many still choose to turn the other cheek.

Now comes Lee Isaac Chung’s Twisters, a standalone sequel to De Bont’s prescient piece of blockbuster trash. Though decades have passed since the decline of the disaster movie, Twisters keeps the spirit alive. It’s the same schmaltzy, hokey, and campy form of blockbuster, but unlike the box-office movement it harkens back to, it manifests as escapism with a conscience. As we get caught in its spin cycle, we’re allowed a rare peek at the human and political shades of climate change. While there is no mistaking Twisters for high (or even low) art, Chung manages to tap into our complicity and our deepest, sensual urges in some clever ways.

Twisters’ plot repeats many of its progenitor’s beats. It too begins with its protagonist facing extreme loss at the hand of a tornado, with heroine Kate Cooper (Daisy Edgar-Jones) losing her boyfriend Jeb (Daryl McCormack) to a storm-chasing expedition. Years later, she’s lured back to the storming fields of Oklahoma by her sole surviving friend, Javi (Anthony Ramos), to test a new revolutionary 3D tornado modeling system. She soon butts heads with Tyler Owens (Glen Powell), a charming “hillbilly with a YouTube channel” who shoots fireworks through tornadoes when he isn’t busy signing autographs. As the storm season intensifies, the two competing parties vie to capture the biggest twisters.

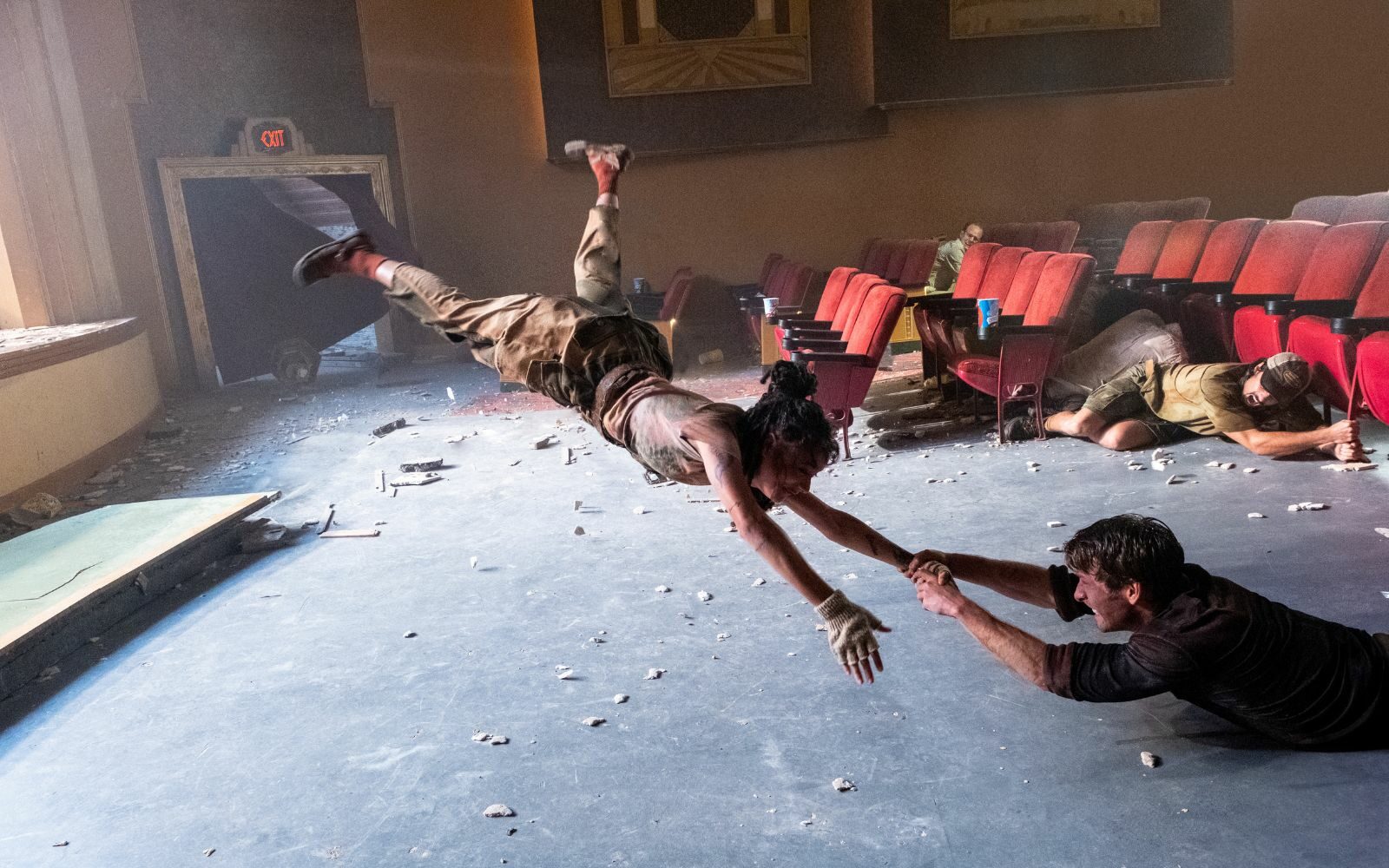

In between the stupidly clever and plot-hole-heavy spectacle of Twisters—which involves an emblazoned oil refinery and a crumbling movie theatre playing Frankenstein (1931)— the story widens to explore who profits from denying, and ultimately intensifying, climate change.

As the truth comes to light about the true investor of Javi’s company, a land developer who swoops in to purchase recently leveled property on the cheap, Twisters begins to weave an interesting wrinkle into the disaster movie formula. Chung’s film touches on our penchant to profit off devastation, in turning one person’s calamity into opportunity. Why stop tragedy from occurring, when you can capitalize on it? In subtly and unsubtly probing such questions, Twisters looks to evolve the sub-genre from the inside out, setting its sights on not only the eye of the storm, but the people and systems that enable the increasing politicization and monetization of climate change. It’s the kind of perspective that’s to be expected from the director of the Oscar-nominated Minari, which too focuses on our connection with the Earth and how our attempts to mould it only serve to mould us.

As the story shifts from tracking and studying tornadoes to developing a way to stop them completely, Twisters’ dumb subversion of the disaster movie reaches a rousing crescendo. Through its senseless science babble, the film not only relishes in the constraints of its sub-genre, but works to flip them on its head, attempting not to evade the worsening climate that enables such blockbusters like its predecessors, but actively prevent it. It’s the rare disaster movie that presents a proactive model, instead of a reactive one. It hopes we can work, in spite of economic and political interest, to mitigate the type of devastation and disaster that greenlights movies like it.

Chung’s Twisters also holds within it some stirring symbolism, with each cataclysmic tornado doubling as a sly metaphor for an orgasm, a sexual re-awakening in which Kate must fight her fears and doubts to foster a new relationship. In its greatest moments, Twisters finds many of our deepest, most primal urges at the heart of its whirlwind. It’s here where Powell’s picture-perfect casting works wonders. His scintillating cowboy is far more powerful than the tornadoes he chases after, sucking us up and blowing us away with his innate and impossible sense of charisma. By the time he tells Kate “You don’t face your fears, you ride them,” we’ve already entered the suck zone.

While Twisters may look dumb, feel dumb, and play dumb, there’s an inkling of a conscience that’s rarely found in films of the same ilk. Its stance on climate change is far from profound, but it reinvigorates and empowers a long-dormant genre, reminding us of the primal, human, and political face of climate catastrophe.