By Cam Delisle

In the wake of her breakthrough third album, Through The Wall, the experimental-R&B auteur reflects on a career-defining year.

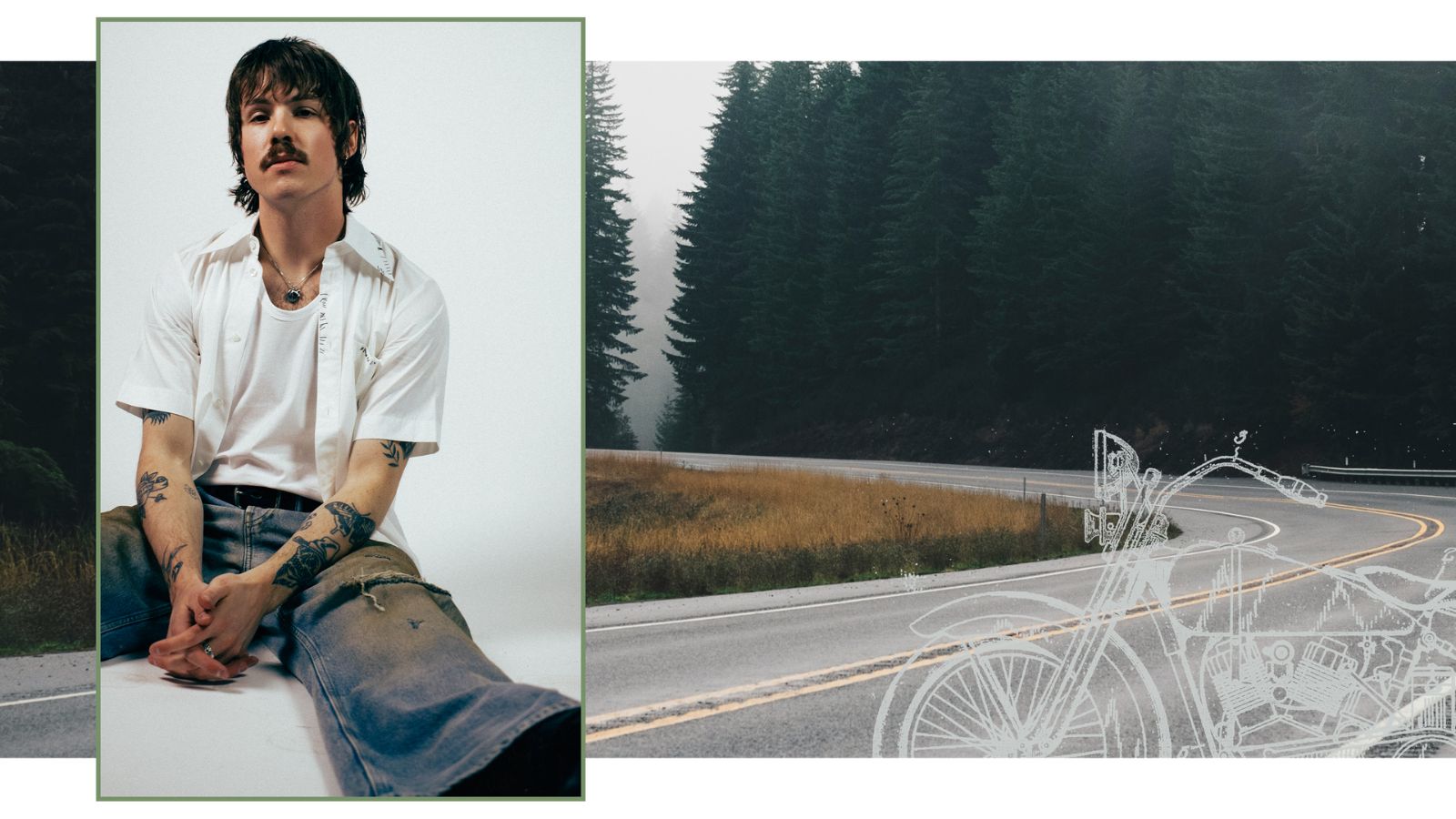

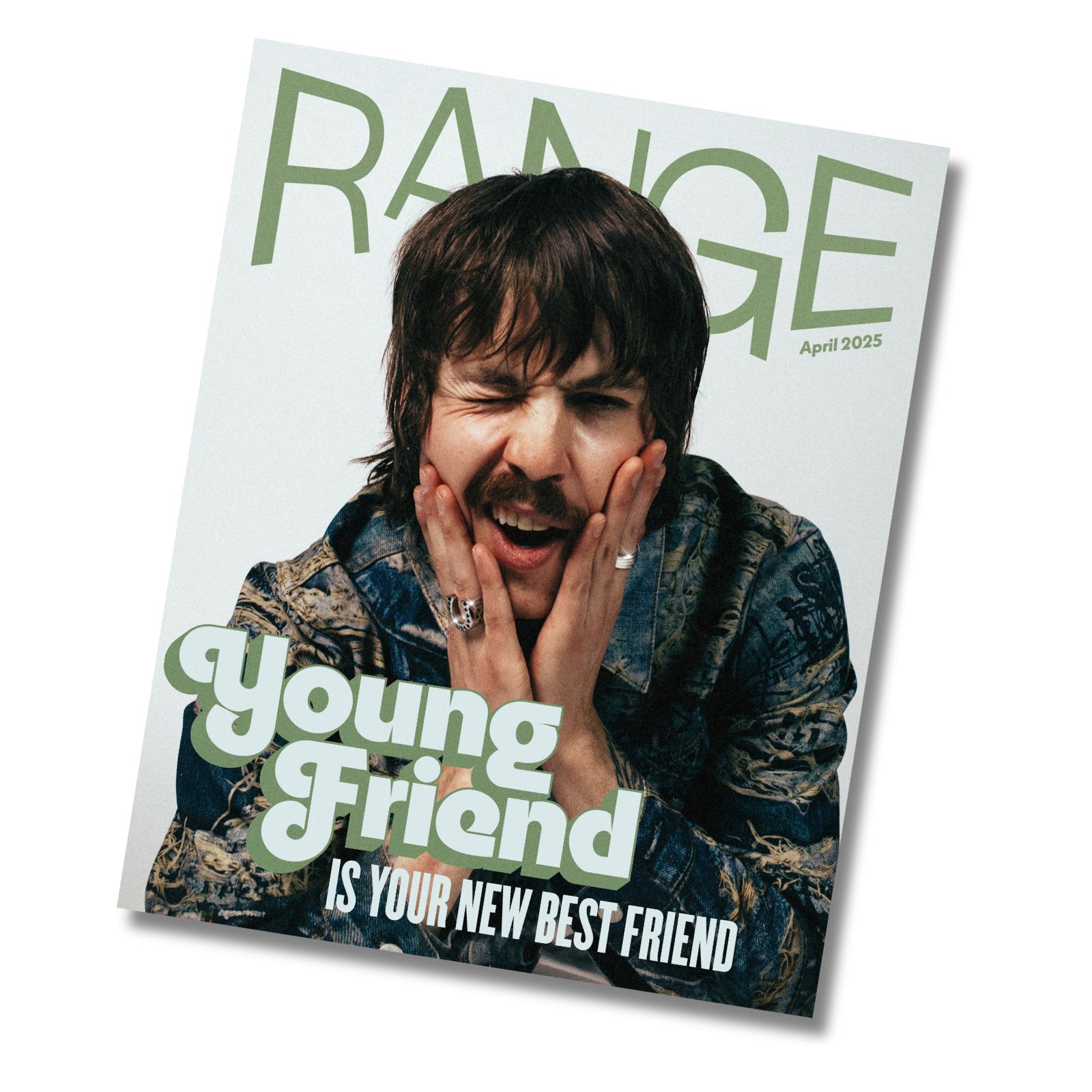

Drew Tarves is a riddle wrapped up in the form of an East Vancouver heartthrob. At first glance, he’s just another guy—with his moustache and sleeve of flash tattoos, you might picture him tucked away behind the counter of a local record shop. But there’s a current running beneath that unassuming stillness: throughout his musical output as young friend, there’s a constant breath of thoughtfulness and creativity that refuses to be boxed in.

His rising fan base is quick to tout him as Vancouver’s reigning indie-pop sad boy—a title he’s quietly claimed through his ability to balance isolation and longing with a kind of unflinching self-awareness—but that’s just one colour in a much larger, shifting palette. Tarves has long outgrown the lo-fi, fractured bedroom-pop of his 2019 debut yours kindly, as each new turn in his music showcases a deeper dive into the porous, tangled web of his sound, self, and all the spaces in between.

Before we even sit down to chat, he cracks a smile and tells me that he wants to start lying during interviews just for the hell of it. It’s at this moment I can tell this conversation is going to be just like his music—tongue-in-cheek, sharp-edged, and disarmingly honest.

Wardrobe from gravitypope.

Tarves’ stage name, young friend, is a fitting pseudonym for an artist of his character. His music breathes with the same effortless wit as his personality, laced with a conversational intimacy that mirrors the kind of ease you’d find in a late-night chat with a close friend. The name “young friend” carries a surprising literalness, rooted in a moment much simpler than a desperate yearning for a stage name. “I was out with some of my friends who were a lot older than me,” he recalls. “We were going back to one of our friends’ houses, and I asked, ‘Is it okay that we’re all coming over?’ There were like eight or nine of us… and he was like ‘Don’t worry, my dad loves you because you’re my young friend.’” As he sits across from me in a DIY underground music venue-turned-photo studio for the day, his cheeky smirk cements it—he’s the kind of guy who can confidently claim, “Moms love me!”

For Tarves, creativity has always been an instinct, a force as intrinsic as breath. With 11 years of formal dance training in ballet, he describes the shift between mediums as something that occurred organically. “When I started experimenting with learning an instrument and eventually writing songs, it didn’t feel that different than creating something with dance,” he reflects, illustrating that what others may refer to as a pivot, he simply views as the next step. While some artists succumb to the pressure of labels or external expectations to “level-up” their persona and sound, Tarves frames his evolution as a balance between authentic development and intentional growth. “I’ve only been playing music for seven years or so… I think the more songs that you write, the more you learn about how to write and structure a song,” he begins, articulating that alongside his thirst for knowledge lies an insatiable drive—a compulsion to “be better and constantly [try] to write the best thing.”

Co-penned with friend, collaborator, and producer marinelli, his new album, motorcycle sound effects, marks Tarves’ first full-length record, following a trilogy of EPs and a series of singles—most notably “PINCH ME,” which has amassed nearly 50 million streams on Spotify. In September 2022, the pair retreated to a cabin on the Sunshine Coast, the quiet starting point of what would later lay the groundwork for the album.

“There was no wi-fi, barely any cell service, an electric hot-plate for a stove, and we stayed there for a few weeks… writing, experimenting, and playing around,” he details. He emphasizes how the record began as “folky” and “warm,” but the tug-of-war between L.A. and Vancouver twisted it into more of a rock-leaning project. “I feel like having written the album in these two super opposite places, you get pieces of both of those places on the record,” he continues. Just like his sound, Tarves himself is the product of a similar dichotomy—calm and chaos, humour and heartache. His music speaks to these contrasts, capturing the tension of growth and the bittersweet nature of leaving one chapter behind to embrace the next.

With a somewhat-facetious sensibility that defines itself through the music, Tarves’ confessional nature on motorcycle sound effects feels as disarmingly candid as it is delightfully playful. “I love motorcycles. They’re one of my favourite things,” he says, as if the very act of saying it was both a disclosure and a punchline. For someone who had just moments prior shrugged off the title of “funny person,” Tarves effortlessly cracks jokes, as if humour is a side effect of his natural charm. “There originally were some motorcycle sound effects on the album, but we took them off…” he reveals, explaining that a friend of his proposed the title, to which Tarves initially retorted, “absolutely not.” Three months of contemplation later, he recalls the sudden flash of clarity: “Now it feels like it perfectly encapsulates what the record feels like to me.” And as for those sound effects? He offers a simple verdict: “They didn’t sound very good.”

The record is a concise, 12-track offering that maps Tarves’ perplexity—both with himself and the relationships that surround him. There’s a tension between confusion and clarity, co-existing in someone who’s—on the outside—never seemed more sure of themselves. On tracks “boyfriend material” and “i like girls,” he wrestles with the uncomfortable recognition of his own toxicity. The aforementioned track finds him cooing, “Used to like when life was easy, now it sucks ‘cause someone needs me,” floating over a Bon Iver-esque piano riff. Sonically mirroring the album cover with uncanny precision, pop-rock head-boppers “loose” and “eye to eye” carry the feeling of flying down an open road, while, in contrast, “sweet tooth” and “trouble” play their hand at pine-scented balladry. In the midst of it all, “the real deal” and “soft light” narrate that earlier-noted warmth and quiet solace—the same kind of calm that washes over him when he talks about his music. It’s as if his every word holds a subtle mastery, and even the way he rests his hands during our interview speaks to an artist completely at ease with his craft.

In shaping the album’s final sequencing, he reveals that he wrote 26 songs for the project, with the finished album representing less than half of that. “There’s a lot of songs that I really loved that just didn’t quite fit within the sequencing,” he confesses, joking that “there was also just stuff that was garbage,” as though discarding songs is as normal as throwing out old socks. While some might file those tracks away for a future release, Tarves contemplates, “those songs are always gonna exist in the world of this record,” and that it would “feel wrong to take those and paste them onto another project.” It’s the signature of someone who sees a body of work as a unified entity, not a patchwork of isolated singles stitched together. His dedication to a consistent whole bleeds through even in the way he channels his influences. “I feel like my references came a lot more into play during the mixing process, [for example] having references that we wanted our mix to sound like,” he explains, further noting those influences as Father John Misty, The Strokes, and Mount Eerie.

While some artists chase the pressure of a “right moment” to drop a full-length, Tarves takes a different route—one with a bit less urgency, and a lot more intention. “I’ve always said that when I drop my first album, I want to have earned it,” he says, as if the whole process of creation is an initiation of sorts. It’s a mindset that mirrors his entire approach to music—less about hitting milestones, more about taking the long road, letting the path unfold as it will. “When we started writing it, I was like, ‘I think I’m ready to do it!,’” he laughs, then pauses. “And now that it’s almost here, I wish there was more time, because you only get to do it once.” He trails off, and in the quiet that follows, you can almost hear the weight of the months spent obsessing over this project. But there’s no regret in his voice, just that wry, almost too self-aware acknowledgment that this ride’s ending. “It’s a bittersweet thing,” he says, as though the concept of moving on to something else was as inevitable as another cup of coffee. That “something else” doesn’t carry the same heaviness—it’s not about what’s behind, it’s about what comes next, and he’s bringing us all along for the ride.

By Cam Delisle

In the wake of her breakthrough third album, Through The Wall, the experimental-R&B auteur reflects on a career-defining year.

By John Divney

Still processing their debut album, Vancouver’s latest art-rock unit proves collaboration is the new rebellion.

By Cam Delisle

The elusive Kevin Parker soundtracks the self-medicated search for bliss on his fifth album, Deadbeat.