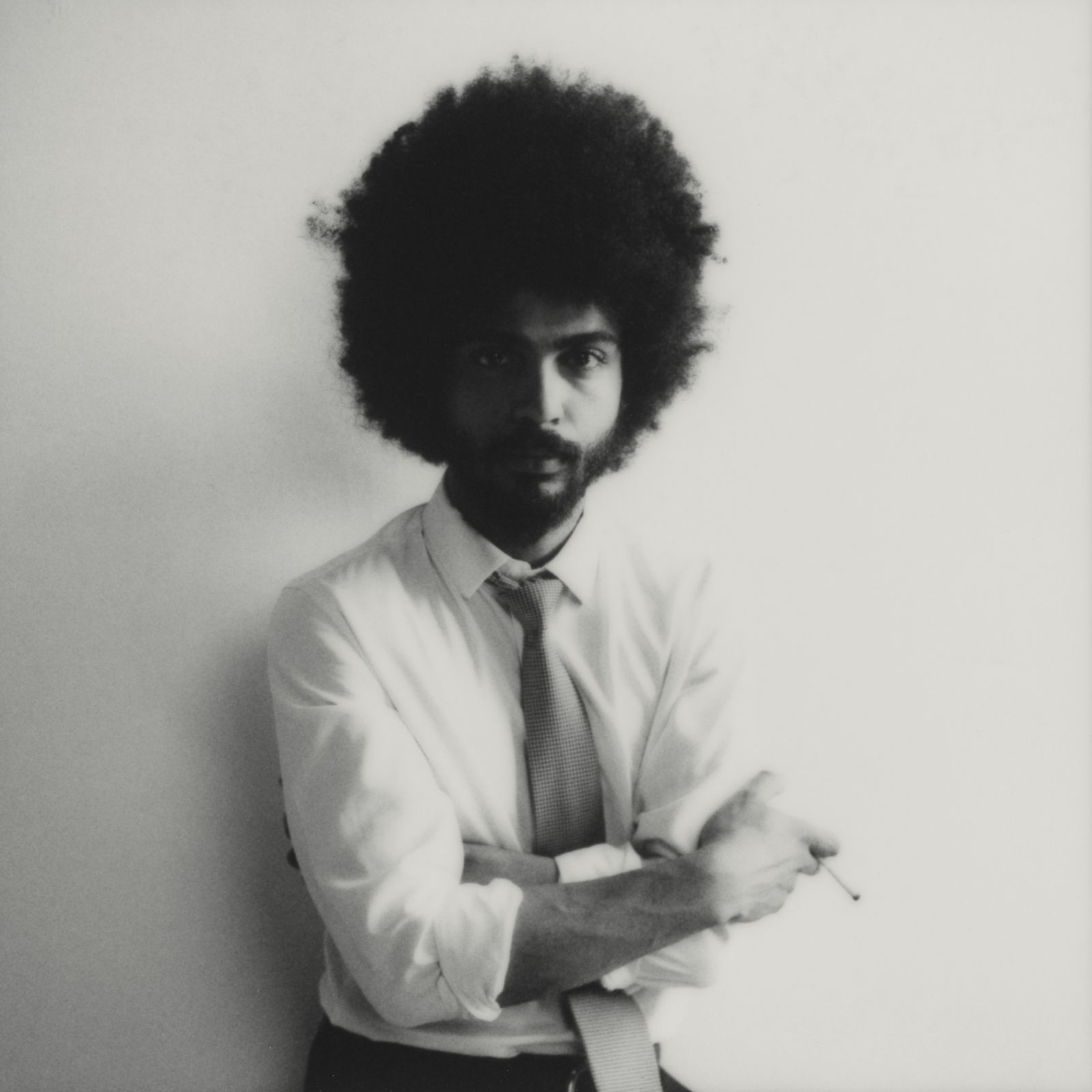

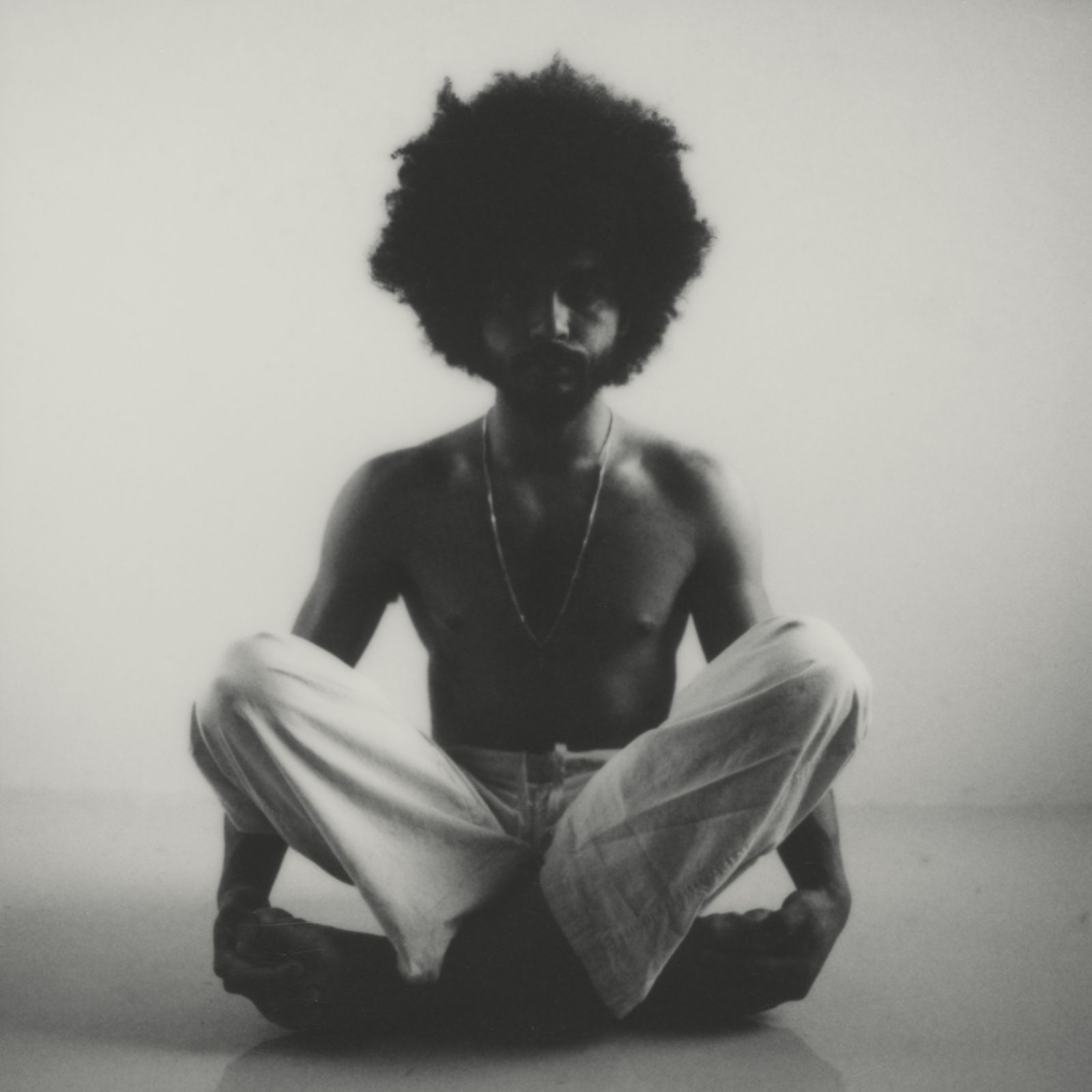

By Megan Magdalena

A sold-out night at the Vogue Theatre brought Warped Tour memories roaring back.

That’s also the kind of feeling you get when listening to his music, a cavalcade of switch-ups and fleeting motifs that’s difficult to ascribe a genre label to. In any case, though, Jarvis will tell you that as he ages, he’s trying to get a little more accessible. Wanting to achieve the effect where the songs take on a life of their own, almost becoming bigger than the artists, Jarvis found an unexpected source of inspiration: the music of Frank Sinatra.

“For me, he’s the guy!” Jarvis says. “I love orchestration, I love the pomp, the grace, the storytelling. That’s what brought me to his discography, but what kept me there was Sinatra himself. Just his affect and the way he dances around, his cadence. I heard people say that you can’t pin his vocal down; he’s always dancing around the rhythm.”

Jarvis has previously mentioned that he felt some of his previous works, while very important to himself as a means of expression, weren’t as listener-friendly as they could have been. Sinatra is probably one of the most-covered artists of all time, and the degree to which your average karaoke patron wants to interpret his timeless tunes is something that’s newly meaningful to Jarvis.

“I love the singer-songwriter and the confessional, but then there’s another aspect to music that’s the interpretive,” he says. “The less self-involved, the more universal. Both avenues are good to get there – talking about the personal resonates with a lot of people, but I think there’s just this other side of the coin that I was like … ‘I want to interpret my own songs.’”

That desire for the universal extends throughout just about everything he’s doing at the moment – for example, his new album’s title, All Cylinders, is a reference to the firing cylinders in a car’s engine. While Jarvis says that this isn’t quite sonically engineered to be his “car record” yet – the one to play while cruising through a picturesque landscape, and something he says he’d like to do in the future – he was trying to tap into “road music,” something that he says been in the cultural zeitgeist from the earliest recorded tales of travel to Kendrick Lamar’s GNX.

“This is a motif that is present in the arts forever: the road, the driving,” he says. “These symbols are inexhaustible wells of information. When Bowie says ‘Great artists steal,’ it’s cheeky, but the notion is that we are all the same, and we are also inexorably unique and individual. So we owe it to ourselves to tap into the canon of motifs and give our take on it, because that’s really what it’s all about. There is no reinventing the wheel, right?”

Jarvis has always found more artistic fulfilment in locking himself in the studio and toiling until he emerges with something beautiful than in live performance, but his new mentality has also been giving him a new appreciation for heading out on the road himself. A lifelong fan of stand-up comedy, he sees more of a parallel between that art form and his own.

“I love stand-up and they can only work out their material on the road in front of audiences in performance,” he says. “You need the feedback – audience dynamics, seeing the kinds of arrangements that people gravitate towards and the kinds of things that make people quiet down – in order to mold the material, and so that’s important for me as I get older.”

When Jarvis does get back into the studio, though, he certainly won’t be using any fancy gear. In fact, in addition to resorting to some of the cheapest mics, guitars, and the like on the market, all of All Cylinders was recorded on the free-to-use platform Audacity. Jarvis’ main reasoning for this is that he feels the emotions and messaging he’s trying to communicate should be powerful enough to succeed without the use of hi-tech tools.

“You listen to music throughout history, it’s only sounded crisp for about 50 years! How crazy is that?” Jarvis says. “There’s an element of rawness that is important for my project that makes me neglect gear. I’m actually just thinking about, what is the point of this? Well, the point is to express something, and I’m not going to make that gear dependent. My priorities have been perfecting and making it as immediate as possible for me to perform in a recording setting, like lightning in a bottle.”

Jarvis goes as far as to say that consumers of music have been so trained to expect perfect, polished production from the world’s biggest hits that something a little more unrefined becomes more interesting to a bigger musical connoisseur. At the end of the day, though, Jarvis believes his talents will shine through.

“It’s not that I don’t care, because production is super important. Sometimes production makes the song,” he says. “But when I’m doing the take, there’s no spot of editing. Editing doesn’t exist. So it doesn’t matter. It could be an iPhone. It’s like, no, it has to be the best performance. And then that’s going to transcend the medium.”

By Megan Magdalena

A sold-out night at the Vogue Theatre brought Warped Tour memories roaring back.

By Stephan Boissonneault

With There Is Nothing In The Dark That Isn’t There In The Light, the veteran vocalist leans into intimate, searching folk.

By Sam Hendriks

A refined turn toward clarity reveals Melody Prochet at her most grounded and assured.