Lifting the Veil on Atom Egoyan

The Canadian auteur on opera, trauma, and the art of filmmaking.

by Prabhjot Bains

- Published on

Early on in Atom Egoyan’s Seven Veils, protagonist Jeanine (Amanda Seyfried)—a theatre director hired to remount her deceased mentor’s production of Salome—dubs the classic one-act opera the “first recorded sex crime in biblical history.” It’s a blunt, startling statement that not only crystalizes the endless appeal of Richard Strauss and Oscar Wilde’s play, but also directly taps into the core of all the themes that loom over the four-decade-plus career of the Canadian filmmaker.

From the censor board buildings of The Adjuster to the Toronto strip clubs of Exotica to the snowy small-town tragedy of The Sweet Hereafter, trauma meticulously reveals itself through art and artifice in Egoyan’s hands. Desire, alienation, and the pain of broken families manifest in a profoundly cathartic fashion. Such qualities haunt Egoyan’s latest outing, which, in many ways, represents the culmination of all these themes and ideas.

Egoyan, who first emerged in the 1980s as part of the Toronto New Wave (an informal group that also includes Don McKellar, Jeremy Podeswa, and Bruce McDonald) certainly views Seven Veils as the cinematic exclamation point to his body of work. Leaping out of his chair with laughter, Egoyan exclaims “It better be!” In an office brimming with books, he tells RANGE “I have nothing more to say.”

Egoyan first mounted his own version of Salome with the Canadian Opera Company (COC) in 1996—sandwiched between his two most lauded works, Exotica and The Sweet Hereafter—and it’s a story he’s lived with for decades, remounting it three more times, with the 2023 iteration being directly incorporated into Seven Veils. Though, for Egoyan, every story he’s told has seeped into the DNA of the film in one way or another.

“This production ties really specifically into all my themes because it was originally staged between Exotica and The Sweet Hereafter and those films dealt with the same subject matter in discreet and mysterious ways,” Egoyan notes. “Seven Veils was a way to deal with that type of violence head-on.”

“The opera itself has this incredibly grotesque, obscene final image of Salome kissing the head of John the Baptist… and instead of seeing Salome as this ultimate femme fatale, I found embedded in Oscar Wilde’s play a latent psychodrama,” he continues. “The famous dance was an incredible opportunity to understand something in Salome’s past that led to this act.”

Seven Veils allows Egoyan to transpose that same effect onto protagonist (and quasi-proxy for himself) Jeanine, whose repressed, traumatic memories of her father and relationship with her dead mentor spill into her evocative mounting of Salome—much to the chagrin of her financiers. “I wanted to think of creating this alternate version through the screenplay, through this character who would become this modern version of Salome and would make changes to the play,” he says.

However, Egoyan is driven by a need to explore this through setting and characters alone, without reliance on storytelling gimmickry. “It’s almost become a cliché where characters who have a certain type of trauma have it come back through a series of flashbacks and suddenly they understand it,” Egoyan notes. “I was trying to deal with that cliché at the time of Exotica and The Sweet Hereafter, to find another language that could explore how trauma works.”

Seven Veils marks a definitive attempt to deal with such narrative conceits, where pain is reconfigured to create what Egoyan dubs “an alchemical process of traumatization” that not only leads to creative breakthroughs but very personal and intimate ones. Egoyan says, “We think of opera as this very public and monumental process of dramatizing, but it could actually lead to something private and intimate.”

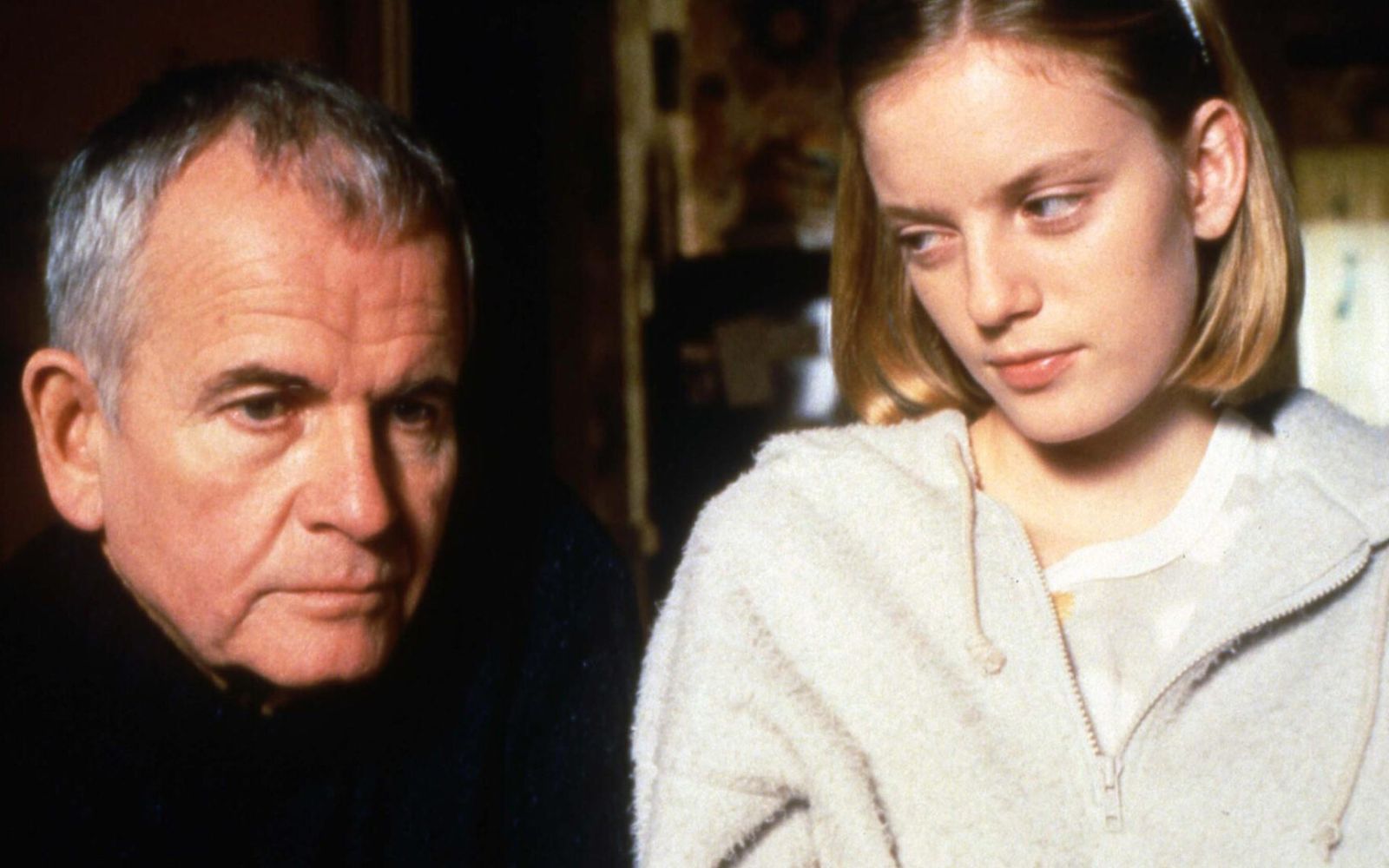

Amanda Seyfried in Seven Veils.

Strauss’ opera first captivated the world in the early twentieth century, but Egoyan finds something in the air of the early twenty-first that further empowers it. In a social media age full of movements like #MeToo and many sharing their trauma in public forums on an unprecedented scale, Seven Veils finds art as a living tree, extending its roots across epochs to yield new and daring interpretations.

“It was the basis of why I wanted to do it.” Egoyan says, leaning forward with purpose. “Salome is a revolutionary piece of music, but there’s something foundational in the story that has transformed itself. This sense of justice people seek to extract from acts of violence, it’s not necessarily going to happen in a traditional, HR route…there are forms of restorative justice people make for themselves.” Moreover, Egoyan notes Salome “is a story that has come to us from a chain of male perspectives in the Bible,” and like all his films, Seven Veils manifests as an intimate and epic reckoning with that.

For as grounded as Egoyan’s film is in the world of opera, it’s just as intrinsically tied to the tradition of cinema, with its garish, slanted stage feeling plucked from the annals of German Expressionism. “We filmed it expressionistically; the camera movements and the use of light were very inspired by the theatrical setting,” Egoyan says. “It’s a story of power and dynamics,” he stresses, with every precise creative choice embodying these themes.

More importantly, though, Egoyan sees his brand of filmmaking as an act of defiance amidst a homogenized cinematic landscape—where a certain “Netflix look” pervades and “there’s this standard way that films have come to look.” He’s thankful audiences are reacting to his disruption of the norm, because he believes other filmmakers have been presenting “a completely industrialized way of shooting, grading, and colouring, and it’s really become quite aggressive.”

“The way Oscar Wilde implants his visual language through his incredible prose, the way he uses the lavishness of language, we as filmmakers are afforded to use the same incredibly sensitive instrument,” he continues. “When you decouple it from industrial expectations and use it in a personal way, it creates something unique.”

Egoyan’s work operates as the synthesis of the sentiment, masterfully unfurling towards moments of sweeping catharsis while embodying the resilience of the frayed human spirits it centres on. Egoyan worries that “as we move towards A.I., this industrialization will become even more extreme.” He hopes people will understand that “there is nothing creative about the act of filming unless it’s given to people who take control and have a clear visual idea of what they are trying to express.”

Now comfortably sitting back in his chair and looking into the distance, Egoyan proclaims “Film is not just a rendering of human behaviour, it needs to be observed and presented in an idiosyncratic way—that’s what makes cinema.” It’s an emphatic statement from a Canadian auteur who has stopped at nothing to peer into the psyche of the human soul.

ATOM EGOYAN FOR DUMMIES

Emerging in the 1980s, as part of the Toronto New Wave (an informal group that includes Don McKellar, Jeremy Podeswa, and Bruce McDonald), Atom Egoyan is a key player in drawing global attention to Canadian stories. From melancholic Toronto strip clubs to snowy small-town tragedy, Egoyan’s cinema of slow-burning catharsis burrows into the trauma of denial, alienation, and broken families with graceful precision. Across 18 films, The Canadian auteur has fostered an uncompromising window into the psyche of the human soul.

We suggest you start with these three.

The Sweet Hereafter (1997)

Egoyan garnered his first Oscar nomination for this look at a small BC town in mourning after a school bus crash kills most of the community’s children. Armed with a spellbinding sense of pacing and his trademarked elliptical editing, The Sweet Hereafter—adapted from Russell Banks’ novel—uncoils as a stirring, empathetic meditation on the beauty and agony of parental love. Ian Holm operates at a career-best as a morally dubious, out-of-town lawyer who prepares a class action lawsuit while dealing with his drug-addicted daughter.

The Adjuster (1991)

While the previous films define Egoyan’s cinematic legacy, The Adjuster remains an early, experimental triumph, containing many of the flourishes that made him a household name: long pauses between dialogue, parallel narratives, unsettling eroticism, and small-town miasma. Yet, the film also finds Egoyan at his most cold and distant, where characters like the eponymous insurance adjuster (Elias Koteas) exist more as ciphers than human beings. The result is a film that exists in an uncanny valley, exposing the thin line between everyday normalcy and hidden perversion.

Exotica (1994)

Egoyan’s first commercial breakthrough is a masterful exercise in withholding information. Meticulously bridging the lives and traumas of its characters, Exotica builds to a sequence of immense catharsis that drastically recontextualizes our perception of the story. Egoyan’s opus rewards repeat viewings, illuminating the unorthodox ways people attempt to cope with inexpressible grief. Also, there’s nothing more Canadian than a CRA auditor at a Toronto strip club watching a dance set to Leonard Cohen’s “Everybody Knows.”

By Glenn Alderson

A deep-listening session reveals how Apple Music’s sonic innovation reshapes the way we hear.

By Cam Delisle

Dominic Weintraub and Hugo Williams take audiences on a treadmill-fueled ride through the chaos and hope of modern life.