Boslen Takes Us On A Trip Through Mania and Moodiness

The rapper discusses the hazards of his profession, weaponizing frequencies, and why he’s never going to leave Vancouver.

By Daniel McIntosh

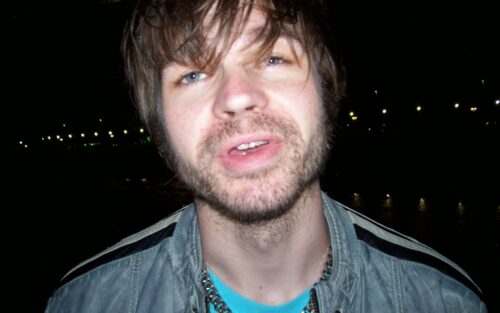

Photo by Cameron Corrado

- Published on

He draws inspiration from artistic risk-takers before him. In a listening session that he hosted at the Universal Music office in Toronto before the release of GONZO, he drifted between references to Salvador Dalí and Christopher Nolan in defining how he finds direction for a project. The latter, whose films challenge and confound viewers, represents an icon of misdirection and intentional misunderstanding. Not everyone will get it, but for Boslen, the few who do are who he wants to address the most.

Boslen’s music is a hair-raising textural wall of sound. Heavy drops, distorted guitars, and spectral screams and snarls inspire listeners to crank their sound systems to 11, if they can stomach it. His latest work is no exception, although the 23-year-old rapper has some new influence in his cadre. While the album’s gritty two-hand intro of “Fallen Star” and “Fiesta” portray a party-ready atmosphere, the affect that appears on “Gone” and “Scars” reveal a soulful interior that draws GONZO into an emotionally arresting state between vulnerability and elation. RANGE caught up with Boslen to discuss the influences that inspired GONZO, putting on for Vancouver, and the grating nature of life on tour.

Hey Boslen, how are you? What’s going on right now?

I’m currently in the studio. I got here two hours ago, just finished a song. It’s a nice, sunny day in Vancouver, and I’m in a good mood.

Congratulations on the tour. I know you had a European leg that was supposed to go down, but didn’t. How was the Canadian half?

It was very good, very eye opening. I had some experiences that, you know, good and bad, that really just shaped me as a man, not even as an artist, which was really dope. And I felt like I grew. My personality grew from it. Because your first tour, the first of anything, is amazing. So I was just very grateful.

When you travel with a big group of people for a long time, I feel like travelling with anybody, that’s when you really learn people’s personalities, because they’re stepping out of their comfort zone, they’re stepping out of their normal routines in life.

And that really helped me. I’d be a hypocrite if I wasn’t saying that I had some self-reflection on that tour about things I need to change about myself. And it’s not like drinking or drugs or anything like that. It’s more just like treating people and talking to people and relations. It was really cool to just see us all evolve and become even stronger.

And then on the positive side, just like seeing the kids. I think, you know, when you go through COVID, and you go through projects, like I dropped a lot of music through COVID. And I never got to see the fruits of my labour. So seeing people’s real emotions and like them telling me stories, it was really cool.

There’s this one show. And this kid came up to me, and he was like, ‘I’m going to make it to all your tour stops!’ I’m like, ‘Are you sure?’ He’s like ‘Yeah, I will!’ And he was at almost every tour stop. That was crazy.

Like a classic like Grateful Dead vibe, tailgating, following the artists on tour. I like what you said about travelling with people. I feel like always when you’re sharing that sort of cramped space, you start to grate on each other. But it’s something everyone has to go through. What’s the reception been like to GONZO on tour?

Truthfully, it’s been amazing. I feel like GONZO, it’s not something that you listen to for the first time like ‘I get it, I completely understand what this is. I know what to classify it as. It’s a hip hop song.’ It’s not that.

I played “Manic,” that was always how I started my shows, with the intro for the project. And the reception was insane. I think they didn’t really expect it and I love that! And then I’d slow it down, like when it came to “Scars”, the last song on the project, I’d tell a story about how I made it to everybody. And I felt like it was just some vulnerable moments. So the reception was really good. I was just happy for them to just hear the music and just give them a taste of what the future looks like.

The second half of the tour was postponed or cancelled because of a hearing impairment, a blown eardrum. What’s the recovery process for something like that?

I’ve already seen like six doctors. But essentially the reason why we had to postpone it was because of changing elevations. I’ve been doing everything I can, wearing earplugs as much as possible, resting, not blasting the music. I think it’s also things happen for a reason. You know, I can’t be pessimistic. I gotta be grateful. I think with postponing the Europe tour, it gives us more time to prepare, and really make sure that we give people my all when I do go out there.

The eardrum has also been alluded to in the album. Can you tell me how that came to be and why it was important to represent it on the album?

The best way I can explain it is when you come to a Boslen show, a GONZO show, the first thing you’ll hear is a 440 Hertz [frequency]. And that’s proven back in like World War Two, World War One, I forget what it was. They used it on hypnotizing, psychoanalyzing stuff. That 440 Hz, If you play it for 30 minutes, your blood pressure rises, and you’ll get antsy and anxious. A lot of artists do that. I think Billie Eilish, Travis [Scott] and a couple artists from Vancouver do it as well. They play it with different bass notes. But I wanted to do it because my ear sometimes rings and I wanted people to feel that so at the beginning of my show, I play that ringing like Eeeeeee, just do that for like two minutes. I wanted people to feel what I felt before I go on, because it makes you go gonzo. So it makes you manic sometimes, man, and I wanted people to feel like I felt. It was just cool.

You keep coming back to history, World War Two. Even your mentions at the listening session were all drawn from historical figures. You mentioned Christopher Nolan. You mentioned Salvador Dali. You mentioned thinking about the music in terms of scenes. What are these sorts of figures, these directors or otherwise, what do they mean to you in terms of pushing your own work in new directions?

They’re probably looked at as crazy or they weren’t idolized. This is the most fascinating thing to me. At the time, they were doing the greatest art… like even look at Lebron James. Everybody’s like, ‘Yeah, but Michael Jordan is better’ When LeBron James’ career is over, people are going to be talking about him for years. And that’s just how it goes. People don’t appreciate things until it’s gone.

I feel like my presence in this industry, and what I’m doing for Vancouver and Canada is not going to be appreciated until it’s gone. But I can control that in a way. I feel like with me, it’s about making sure I do my research, pay homage, pay respect to the ones before me. I can’t control the narrative, but I know what I can do is just push the narrative into a direction where I see best for my own career.

You mentioned Vancouver. Since, DUSK to DAWN and Black Lotus, you’ve just always been trying to put on for Vancouver. What other facets of Vancouver inspired GONZO?

I feel like that “chip on the shoulder” type of mentality that people don’t even acknowledge about the city, or people don’t want to turn that face to a city like this. It makes me very hungry. It makes me want to show that there’s much more here. And on the other side of the coin, there’s a lot of things like being trapped in your own isolation, being trapped in your own madness or like your own routine of… it’s like being stuck in your room for years. It’s hard to create. It’s hard to push forward. I feel like that’s where I was in my career at the same time. So it’s balancing both of those things, which truthfully, made GONZO.

Do you think there’s like a plan in the cards for the future to just go out there and make it happen?

Definitely. But I’m never gonna leave Vancouver ever. I think the proximity is there, my label is out there. So I think it would just only be right with some of the connections. Just to push the music forward. I’m just trying to do whatever’s best for the music.

I’m curious about the title GONZO itself, is it drawn from Hunter S. Thompson?

Yeah, well, in a way. That’s where I first read it. But then I researched Salvador Dali. But I researched what Dali did, pushing himself so much to the point where if he falls asleep, he wakes up by dropping a fork. It wakes him up and then he paints something. That’s just GONZO to me. Or somebody telling me ‘you can’t say that.’ Okay, well, you gotta be delusional to do this. Or witnessing other artists chase fame so badly. It’s delusional. GONZO can be interpreted in so many ways, which is why I love the name.

I’m sure you’ve seen that Kanye documentary. He was talking in front of the school and he was like, ‘How is it possible to be overconfident?’ He’s like, ‘You should be overconfident.’ You have to be overconfident in this life, or in school. And your peers, they tell you to push down and be less confident. Like, why is that? It’s funny that I’m saying this right now, because I know some days, I’m not that at all. I balance that as a human.

Thinking about the theme of creativity surrounding GONZO, and even going back into DUSK to DAWN and thinking about the sort of cyclical nature of how the album follows that theme from night to day. Are you more concerned, would you say, with pulling together a thematic work? Or do the individual tracks mean more to you?

Individual tracks mean more to me now, just in this stage of my career. GONZO is supposed to be sporadic. It’s supposed to feel all over the place. I think I still was able to make it feel cohesive. That wasn’t my goal or my intention going into it at all though. I wanted to make a body of work that just represented where I was in my life right now with me battling with personal stuff with my family, battling with not having a stable place to stay all the time, the back and forth. Just the madness of his lifestyle trying to break it and quote-unquote ‘make it.’ It’s difficult man, and GONZO is just being that delusional.

But when it comes to the songs I have a completely different mentality now, compared to when I was creating it. When I was creating it, I probably still had some influence from DUSK to DAWN and that shows on it and that might be like, ‘Okay, yeah, it’s Boslen, this is what Boslen does.’ But I felt like on songs like “Fiesta,” I was truthfully just really just having fun. On songs like “Gone” that was just me being vulnerable and “Scars”, I was trying to truthfully inspire. I can dive deeper into the songs, but everything felt like it had intention, which was cool.

It all came together, in the end. The album is such a clean and easy listen, and I really enjoy listening to it. I’m going to be playing “Manic” over and over again, because that first beat drop just goes so crazy.

You’ve got to see that one live. “Manic” was interesting to make. I remember I had, I don’t know if I’ve explained this, but there were some boys from Toronto, amazing producers, it was like six of them. They all came up to Vancouver to do a writing camp. And they played that sample, that hypnosis sample and they kept playing it. I was upstairs at the time, and I came down. And I thought of falsetto within the first five minutes, but it’s funny because I made the whole song and I have three different versions with just lyrics.

Originally what I wrote, I wrote in the sense of telling a story of some dark person that was just battling their inner demons. I guess the song can be interpreted in that way. But then it transitioned to something completely different. I sent the project to an individual named Anthony Kilhoffer, and he helped me change my perspective on how to write it and make it more about something deeper, because I think that’s what Kid Cudi did. Individuals that I look up to just really show their guts and they’re not afraid to show those guts.

Tell me about the recording of “Scars” as well because that’s a very emotionally wrought track and I believe you’re addressing it to your mother, if I’m not mistaken.

It’s such an emotional song. Every time I listen to it, I choke up. And when I perform, I cry every time. It’s because the first time I made that song, it was in Vancouver. There were three versions for the song. The first one was called ‘Posters.’ It was essentially the same lyrics, but it was in a different flow, a different cadence, it was a bit more uplifting, fucking anthemic.

I remember, I was in the studio and it was nighttime. I was just battling with a lot of stuff. My parents were going through it, financials were going through it. My friends I was recording with stepped out of the room. So I just recorded for 15 minutes straight. And I just closed my eyes, and I just kind of fell out. And I started getting choked up at the mic.

How we pieced it together was really focused on the lyrics. I think I pulled a lot of inspiration from Kid Cudi’s ‘Soundtrack 2 My Life,’ or songs that break that fourth wall. I feel like everything is so in your face, and it’s a good song to just be vulnerable and be human again.

It’s one of the most important songs I think I’ve ever made. You can make a lot of trap bangers and you can make a lot of those club hits which are always needed, but you do need a song that can save somebody’s life. Because I know a lot of songs that have saved mine and I’m just trying to do the same.

By Stephan Boissonneault

Nate Amos revisits a decade of stray ideas and turns them into his most compelling record yet.

By Khagan Aslanov

Mike Wallace’s electro-punk project premieres the hypnotic, percussion-driven video for "Certain Days."