Contemplating Punk: An Exclusive Interview With Danny Fields

The former Ramones manager looks back and reflects on why the “P-word” is the perfect word to describe such an imperfect genre.

By Gregory Adams

Photo Illustration by Alex Kidd

- Published on

“I’m embarrassed to use that word, but still, it’s a perfect word,” he says, ultimately conceding to the genre tag’s lurid allure from a purely typographical standpoint. “It’s four letters and it ends with a ‘K’ — that’s a formula for success.”

Nevertheless, Fields is contemplating punk when RANGE reaches him over the phone at his New York City apartment. Specifically, he’s in the process of putting together contact sheets from a vast archive of personal photographs to bring to NOFX founder Fat Mike’s new Punk Rock Museum in Las Vegas. The hope is that some of these could hang with the rest of the institution’s accumulated hardcore history. His collection is quite iconic, including years of candid Ramones photos—from goofball poolside shots of bassist Dee Dee Ramone, to the brick wall-set stoicism of the Rocket to Russia album cover, as well as curios like the first-ever live performance from Patti Smith and guitarist Lenny Kaye. New York Dolls guitarist Johnny Thunders loungin’ at New York’s famed Max’s Kansas City venue? Sure, he’s got those, too. He wonders, however, whether decadent photos of Alice Cooper “on a boat in a bikini bathing suit” fit the scope of the museum. “Everybody in the world has a different idea of what it means,” he suggests earlier in the conversation of the great punk debate. “Must you have green hair? I don’t know. Must you have razor blades in your nose and tongue? Some say you do.”

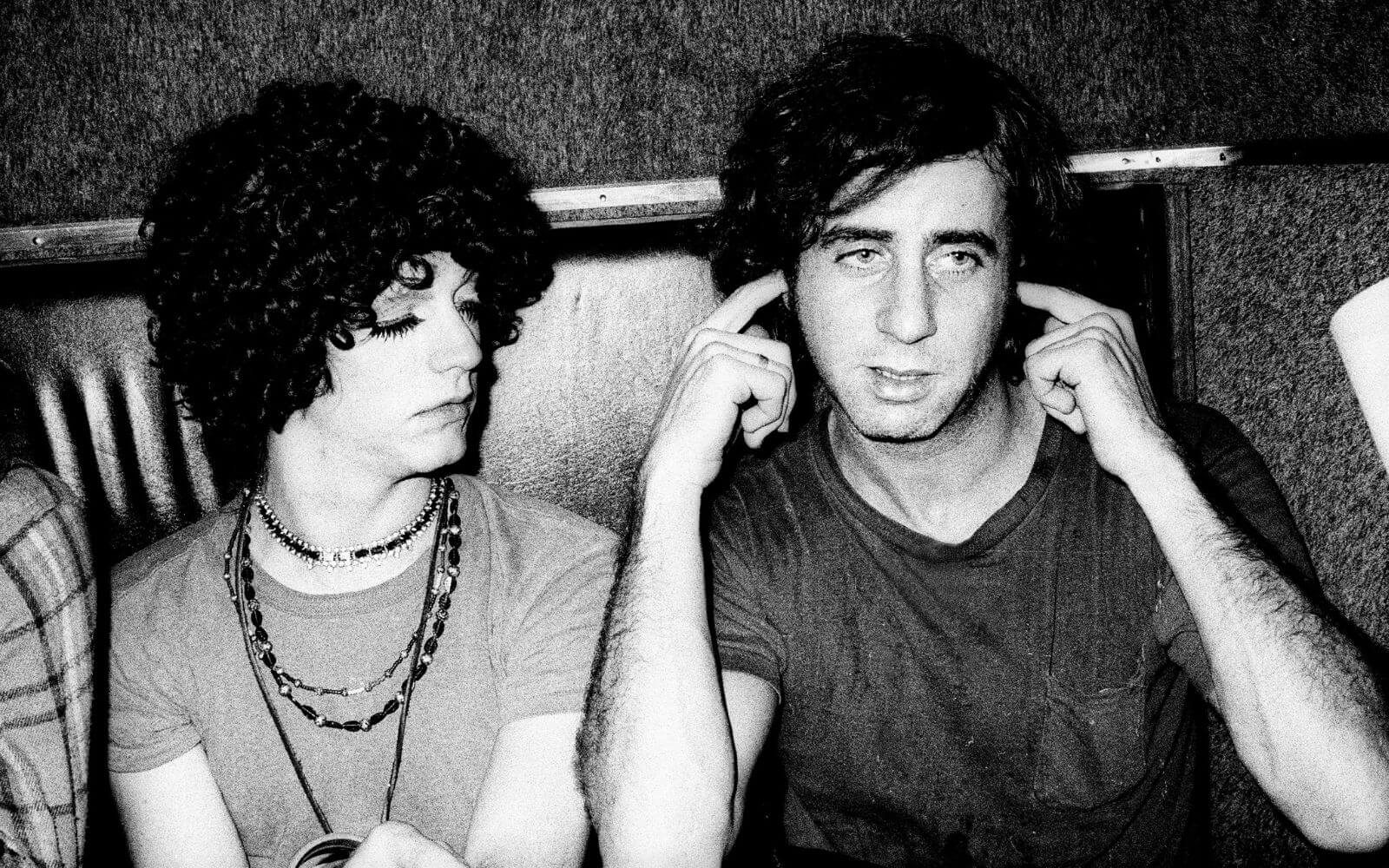

Pristine Condition and Danny Fields in the documentary Danny Says.

“Must you have green hair? I don’t know. Must you have razor blades in your nose and tongue? Some say you do.”

— Danny Fields

Fields’ multifaceted journey through the music industry is likewise a little tricky to define, and almost happenstantial. What’s clear is that while he grew up in a musical family, he had no allusions of becoming a performer.

“My father played eight instruments; he was a genius instrumentalist. He worked his way through medical school leading a band—played saxophone, violin. I took clarinet lessons in elementary school and I hated it; I got splinters in my mouth,” he explains, adding of his talents, “I know technically nothing [about performing music]. I know what I like, though.”

After dropping out of Harvard Law School, the New York-raised Fields found himself back in the East Village, and hanging out within Andy Warhol’s Factory studio scene. He took an editing job at teen magazine Datebook, subversively promoting the Velvet Underground’s sadomasochistic outsider pop to 12-year-old girls, while also striking up a lifelong friendship with photographer Linda Eastman (later Paul McCartney’s wife and Wings bandmate). Most infamously, he printed John Lennon’s quote about the Beatles being “more popular than Jesus” (“I just wanted to make a little mischief, that’s all,” he says to sum up his time at Datebook).

When Fields moved on to Elektra Records, he championed the harmonium-driven “gloom-and-doom” that his friend and former Velvet Underground collaborator Nico ended up releasing as 1968 cult classic The Marble Index. He worked with the Doors, too, but did not get along with Jim Morrison. He more fondly recalls climbing the stairs towards the ballroom of the Ann Arbor student union building as the sneeringly seductive strains of the Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog” reverberated through his bones for the first time. It was irresistible. Somewhat poetically, what sold him on the hyperactive rock and roll of Ramones—within the first 15 seconds of a set—was the cool-but-creepy narrative of their “I Don’t Wanna Go Down to The Basement” (“I’m not big on lyrics, but what a great idea for a song.”).

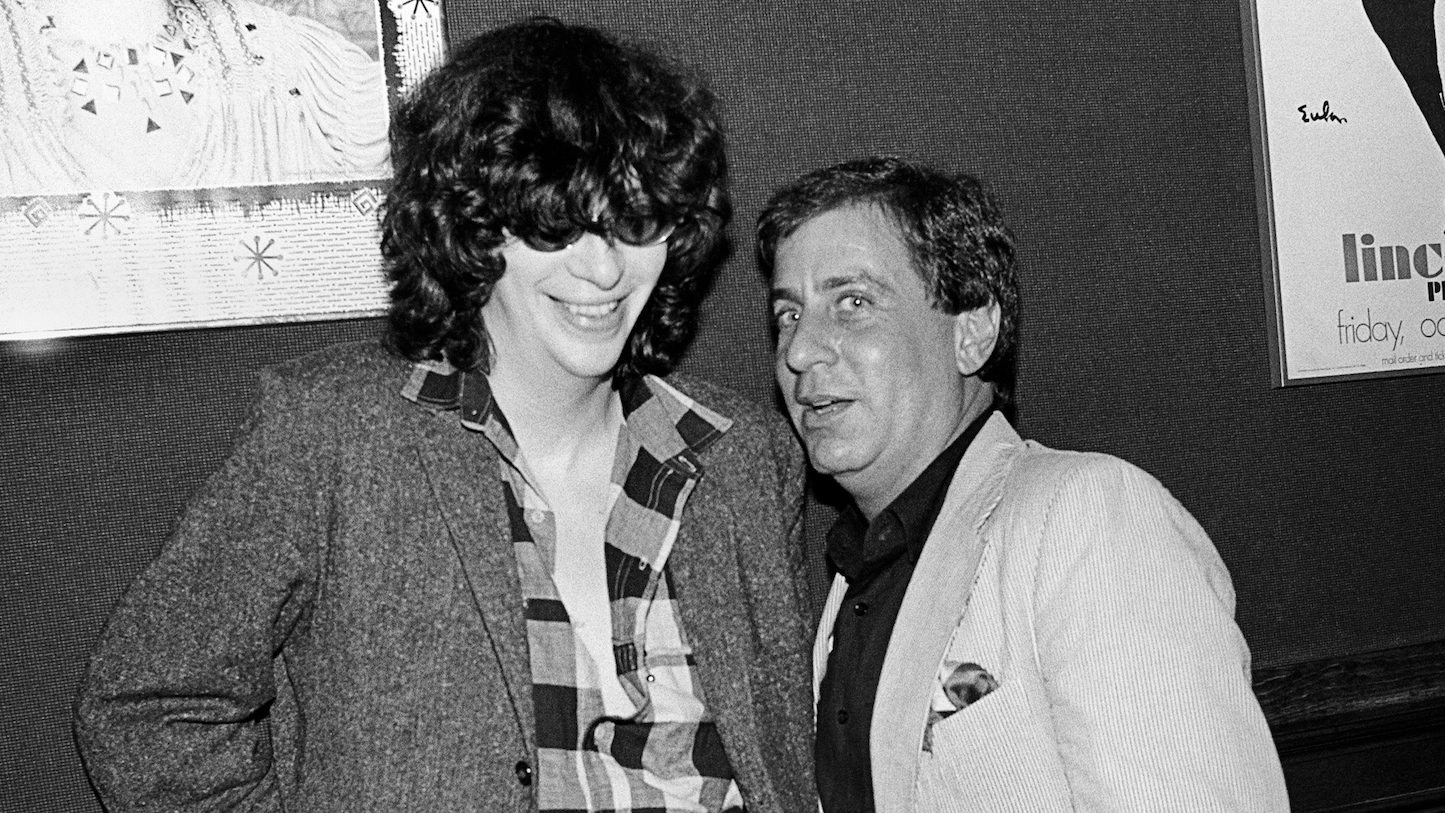

Fields spent five years with the Ramones, and even ended up getting toasted by the band in the first line of “Danny Says,” an aesthetic-growing ballad from 1980’s End of the Century album—its title likewise serves as the name of a 2014 documentary on Fields’ life. Trouble is, Fields feels the shoutout is somewhat of a fiction. Yes, he was technically their agent at the time, but he can’t recall ever telling them to “go to Idaho,” as Joey Ramone puts it in the first verse. He figures the line was actually about Tommy Ramone, who “besides being the drummer and the architect of what the band’s essence would be, [was] also in charge of getting them gigs.” Maybe “Danny” just rolled off the tongue better than “Tommy” did.

“It’s about a guy who misses his girlfriend, and he’s in a band. It has nothing to do with me,” Fields continues, adding with mixed feelings of the End of the Century classic, “[It’s] produced by Phil Spector, so it’s beautiful, but if that was the first thing I heard the Ramones do, I wouldn’t have gotten excited. It’s a pretty song, but it didn’t explode my brain. The power stuff did.”

Joey Ramone and Danny Fields at a Lou Reed after show party at Jerry’s Restaurant in New York City on October 17, 1984. (Photo by Ebet Roberts)

Fields notes that although he mostly ducked out of full-time managing around 30 years ago, he’s still involved in the music biz. In 2018, for instance, he dropped his photo book, My Ramones. The upcoming plans with the Punk Rock Museum are in flux, but may include a stint as a tour guide; he’d similarly dished rock and roll gossip during some New York bus tours in the early ‘90s. If so, Fields could spin a number of stories, like seeing MC5 for the first time, or hanging out in New York apartments with dear friend Nico as she developed an increasingly experimental songbook. Perhaps he’d dive into how the Ramones fired him for not getting them a hit record—to be fair, they never managed that without him either. And yet, the Queens outfit’s legacy endures and inspires punks to this day.

“That wasn’t my thing, looking for number one songs, but I had good taste. That’s it,” Fields says. “After a while you get a reputation for having taste that’s a few years ahead of what’s happening. I had that for a while!”

Fields is being a bit modest here. True, he’s nary touched a clarinet in decades, but that impeccable tastemaking—reflected in revered records from the Stooges, Ramones, MC5, Nico, and more—remains timeless.

The Punk Rock Museum has invited Danny Fields to check out the museum in person and discuss an upcoming photo exhibition to take place in 2024. Stay tuned for more details! (Photo: Lisa Johnson)

By Leslie Ken Chu

The rock stalwarts lean into vulnerability and nuance, proving that evolution doesn’t have to mean softening the blow.

By Cam Delisle

The pop veteran beamed into Rogers Arena Tuesday night with a glitchy arsenal of remixed hits—some faring better than others in her AI-styled end-of-the-world fantasia.