By Ben Boddez

Jasamine White-Gluz’s love of creepy crawlies inspires a project reflecting the many sounds of nature through a shoegaze lens.

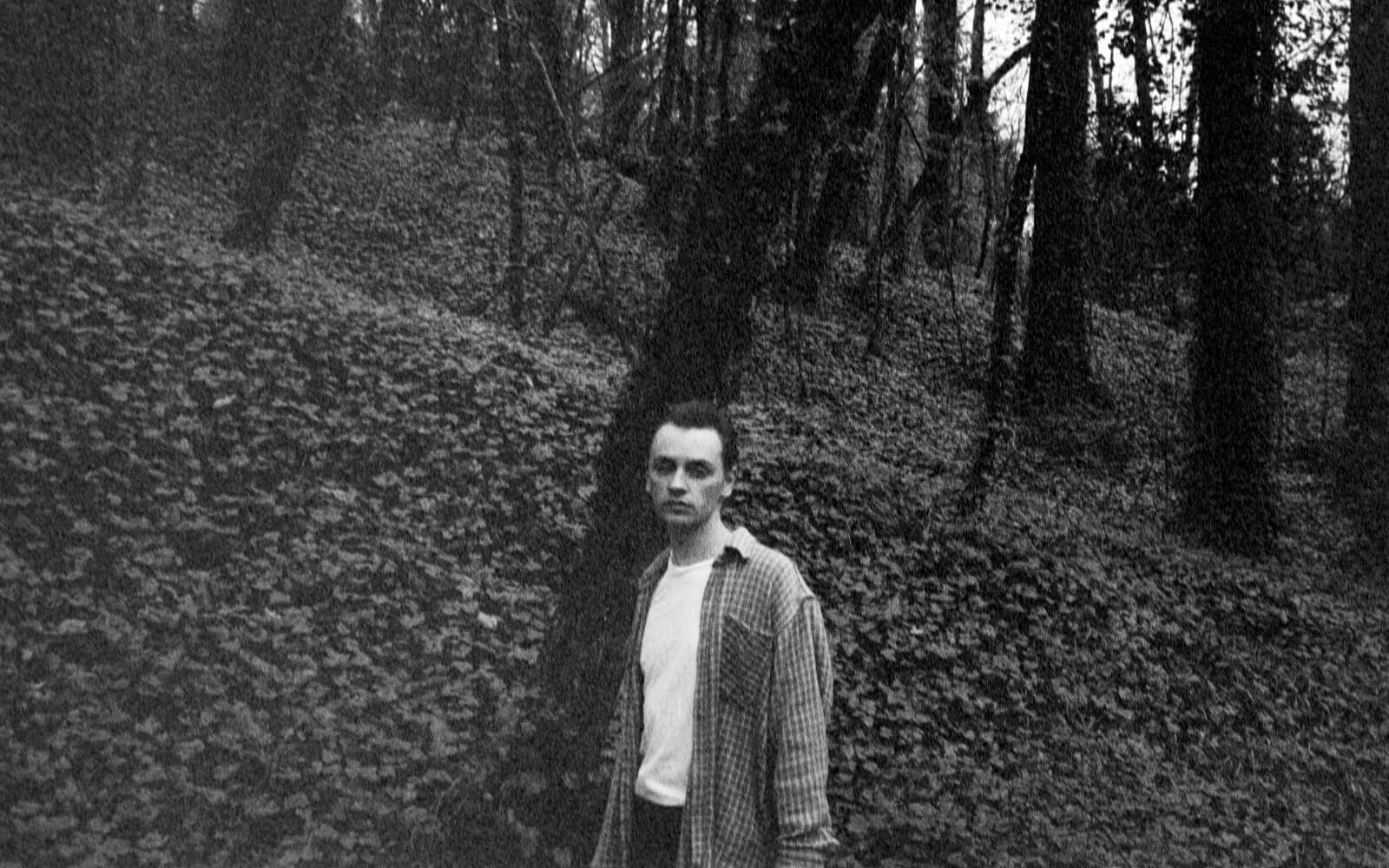

“It was a surreal moment I still think about quite a bit, and I remember this stomach-plunging sensation,” Allen says, connecting through a computer screen from his newfound home in Atlanta, Georgia. That sensation now manifests in a heart-wrenching ode on the song “Mirage,” off of Puma Blue’s upcoming second full-length album, Holy Waters.

Around the time he was writing for Holy Waters, Allen revisited that surreal memory and became increasingly depressed, realizing that he had never fully processed what had happened.

“That song comes from an emotionally fresh place,” he says, pausing for half a minute to find the right words. “There’s so much that we feel is inexpressible or indescribable, and music almost articulates it for you in a much messier way that’s less about language and more about a free form of expression.”

But those free forms of emotional expression don’t just happen overnight. After his debut, In Praise of Shadows, came out in 2021—earning him a following in the UK and across the pond—Allen found he had hit a wall. He couldn’t write anything worth working on and says he began to go a bit insane, starting to mentally spiral. “I was starting to think ‘Maybe I should rethink my life,’” he says. “How can I call myself an artist when I can’t even make art?”

What snapped him out of his spiral was watching the music documentary The Beatles: Get Back over Christmas. It’s a series he calls a “demystification of The Beatles,” musicians often revered as songwriting gods. Get Back, instead, showed The Beatles in a different light; a band who constantly gets distracted and loves to goof around. “It showed me that I was overthinking it all and that I should make music the way I did when I was a child, by trying stuff out and having fun, and I wanted to involve the band more,” he says.

After that epiphany, the musical ideas came flooding in, and it was soon time to hit the studio. He met up with his band in Eastbourne, a town in East Sussex, at Echo Zoo Studios, armed with a bunch of demos with about a third of the lyrics finished. In Eastbourne, Allen and the band found a sense of fellowship. Most of the days were dedicated to getting the instrumentation of the songs finished, but they also lived above the studio, cooking for each other and swimming together on the south coast of England—which happened to be walking distance from the studio—whenever creative walls were hit. “We would work on the music and whenever we needed to be refreshed, we would jump in the sea, and it was a good way to get out of our brains for a bit and into our bodies. So we would always come back ready,” he says.

Allen says his time in Eastbourne with the band was crucial for Holy Waters’ general vibe. At times, it feels very much like an album filled with jams created on the spot by a band with an uncanny chemistry. This is most evident on the song “Gates (Wait For Me),” which blossomed from an extended jam. “I started playing these chords, not really thinking out what I was doing, and Harvey [keys/sax] started noodling on piano,” he says. “I was just in a mood like ‘I’m going to will this song into existence right now. It became one of my favourites on the album.”

The instrumentation on Holy Waters is quite freeing and fun, but lyrically, it could be called Puma Blue’s darkest work yet. As with the song “Mirage,” the themes of death and grief make their comfortable homes throughout Holy Waters. The album, however, isn’t so much about the tragedy of these inevitabilties but the beautiful acceptance of them. It’s Allen coming to his own sort of peace with death, conveyed through his soft poetic musings, swelling underwater guitars, subtle freak-out saxophone, and fusion of rhythmic bass and sometimes off-kilter drums. Take the song “Epitaph,” about the passing of his grandmother. Its title makes it sound like a sombre reflection, but when Allen wrote it, he says that it came from a place of love rather than grief.

“I think it’s kind of beautiful that the listener can either take their own meaning, or even better, have their own experience with it, and not think about why I wrote it,” he says. “That’s when music really crosses some kind of profound line. That’s why I love it.”

By Ben Boddez

Jasamine White-Gluz’s love of creepy crawlies inspires a project reflecting the many sounds of nature through a shoegaze lens.

By Cam Delisle

The Calgary-born pop powerhouse brought her high-voltage Miss Possessive Tour to Rogers Arena for two consecutive sold-out shows.

By Hannah Harlacher

The Montreal songwriter on breaking up with the industry, choosing process over product, and building a creative life on her own terms.