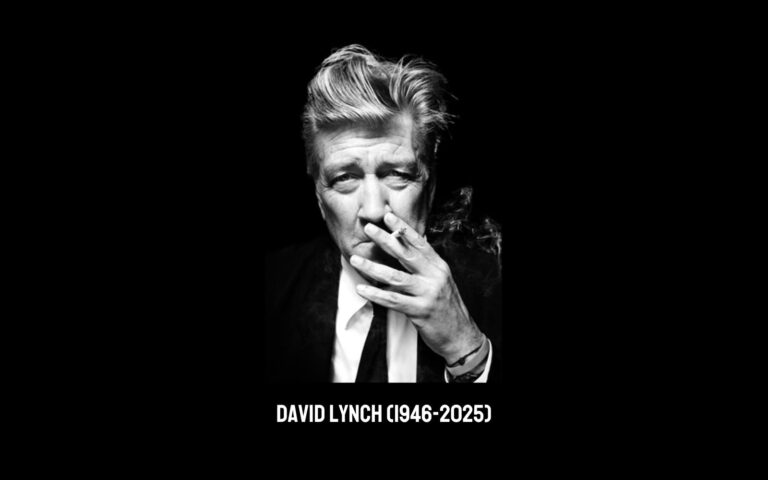

Remembering David Lynch’s Provocative Cinema of Fragmented Dreams and Americana

The prolific director of Twin Peaks, Mulholland Drive, and Blue Velvet has died, age 78.

by Prabhjot Bains

- Published on

In an America that dreamt of security, prosperity, and the comforting sprawl of suburbia, David Lynch’s oeuvre spotlighted all the other, darker fantasies that pervaded: Sex, violence, drugs, and power.

The great surrealist and provocateur of our time bent, contorted, and unmoored the very principles of narrative to his uncompromising vision, entrenching them in endless loops, swirls, and, non-sequiturs until little but a fugue-like stream of consciousness remained. Lynch’s films not only craft amorphous worlds onto themselves but require their own adjective to fully define. The term “Lynchian” has come to epitomize entire cinematic movements, styles, and schools of thought—a descriptor that has nearly become a literary crutch for writers and scholars exploring the darkest, strangest corners of art and creativity.

Across charming Pacific Northwest diners, the festering corners of suburban idyll, the thresher of the Hollywood machine, and the lost highway of a guilty mind, Lynch injected experimentalism into the mainstream, vigorously stirring the tenets of noir, horror, soap opera, and the erotic thriller into one heady, dreamy cocktail. As if inked from the same blotches of absurdist pioneer Luis Buñuel (Un Chien Andalou, The Exterminating Angel) and the Golden-Age Hollywood melodrama of Douglas Sirk (All That Heaven Allows, Imitation of Life), Lynch harboured a twisted, disturbing—but ultimately romantic—view of Americana that seeped into the hardcore of all his work.

In the late 1970s, he burst out as a countercultural force with his debut feature Eraserhead, an inscrutable, monochromatic dive into the fears of parenthood, starring Jack Nance—who would become a regular in multiple Lynch productions— alongside one of the most grotesque infants committed to film, haunting the frame as a sort of oversized reptilian spermatozoid.

The industrialist cacotopia of the cult classic gives way to an early ’80s, which saw Lynch at the helm of more accessible, conventionally plotted experiences. The hazy black-and-white tragedy of The Elephant Man, which stars John Hurt as the exploited carnival attraction alongside Anthony Hopkins, garnered Lynch his first Oscar nomination. While his beleaguered, box-office-bombing adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune (which he chose to direct over Return of the Jedi) would find cult appreciation decades later. Lynch would return to this more approachable verve in 1999 with the gentle and heartfelt The Straight Story (a film that outdoes its title in many subtle and affecting ways), starring Richard Farnsworth in the true story of a man who drove his lawn tractor from Iowa to Wisconsin to visit his estranged, dying brother.

Dennis Hopper and Isabella Rossellini in Blue Velvet (1986)

Yet, 1986’s Blue Velvet established Lynch as a singular, daring American auteur. Echoing his own fascination with a hidden, more sinister America, Blue Velvet’s tale of a clean-cut prodigal son discovering a severed ear on the ground, and then an obsession with a nightclub singer and her sexually unhinged, oxygen-huffing gangster boyfriend (who doubles as one of cinema’s most memorable and terrifying creations), illuminates the visceral, psychosexual soil that fosters the nation’s suburban utopia. From then on, Bobby Vinton’s classic song of the same name would be tinged with a much darker connotation. Lynch would carry that same transgressive edge to his divisive, Palme D’or-winning Wild at Heart. Starring Nick Cage as parolee Sailor, sporting an iconic snakeskin jacket, and Laura Dern as the free-spirited Lula (who by then became stock company for the director), the film unfolds as the cinematic equivalent of a coked-out rainbow that directly draws on Lynch’s enduring fascination with the Wizard of Oz—a quality further explored in Alexandre O. Philippe’s aptly titled documentary Lynch/Oz.

Kyle MacLachlan and Sherilyn Fenn in Twin Peaks (1990)

Yet, most remarkably, Lynch set the stage for the Walter Whites, Tony Sopranos, and Don Drapers of the world with the groundbreaking Twin Peaks (1990), a brightly lit, jazz-scored deconstruction of the soap operas of its time, predating today’s prestige TV landscape by decades. Its story of strait-laced FBI agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan, another Lynch fosterling) investigating a metaphysical murder mystery, takes us to such planes as the haunting, red-curtained “Black Lodge” before it originally concludes with an assurance to continue the story 25 years later. The masterful third season, dubbed The Return, does just that, eclipsing all expectations while obliterating the line between TV and film, with outlets like Sight and Sound and Cahiers du Cinéma labeling the 18-hour season one of the best “movies” of 2017.

David Lynch on set with Naomi Watts during the filming of Mulholland Drive (2001)

Though, above all, Lynch’s cinema is one of dreams — both broken and realized — of shapeshifting pictures and sounds that vividly paint a fragmented psyche. 1997’s Lost Highway, boasts a hauntingly perfect title sequence set to the tune of David Bowie’s “Deranged” and plunks audiences into the warped mindscape of its insecure protagonist, who may or may not have murdered his wife. While his magnum opus, Mulholland Drive, towers as a portrait of the Hollywood dream machine and the steady stream of nightmares that fuel it. The fraught, sweltering chemistry between the starry-eyed Naomi Watts and the esoteric Laura Harring washes over us like the film they star in, drawing us ever closer into the haunting gauntlet of movie magic.

David Lynch is the rare artist whose work defies the need for interpretation, simply existing as a vessel for pure wonder and feeling. “There’s an ocean of pure, vibrant consciousness inside each one of us” according to Lynch, and his lush cinema of dreams, desire, and Americana entices us to take the plunge every single time.

By Glenn Alderson

A deep-listening session reveals how Apple Music’s sonic innovation reshapes the way we hear.

By Cam Delisle

Dominic Weintraub and Hugo Williams take audiences on a treadmill-fueled ride through the chaos and hope of modern life.