By Cam Delisle

In the wake of her breakthrough third album, Through The Wall, the experimental-R&B auteur reflects on a career-defining year.

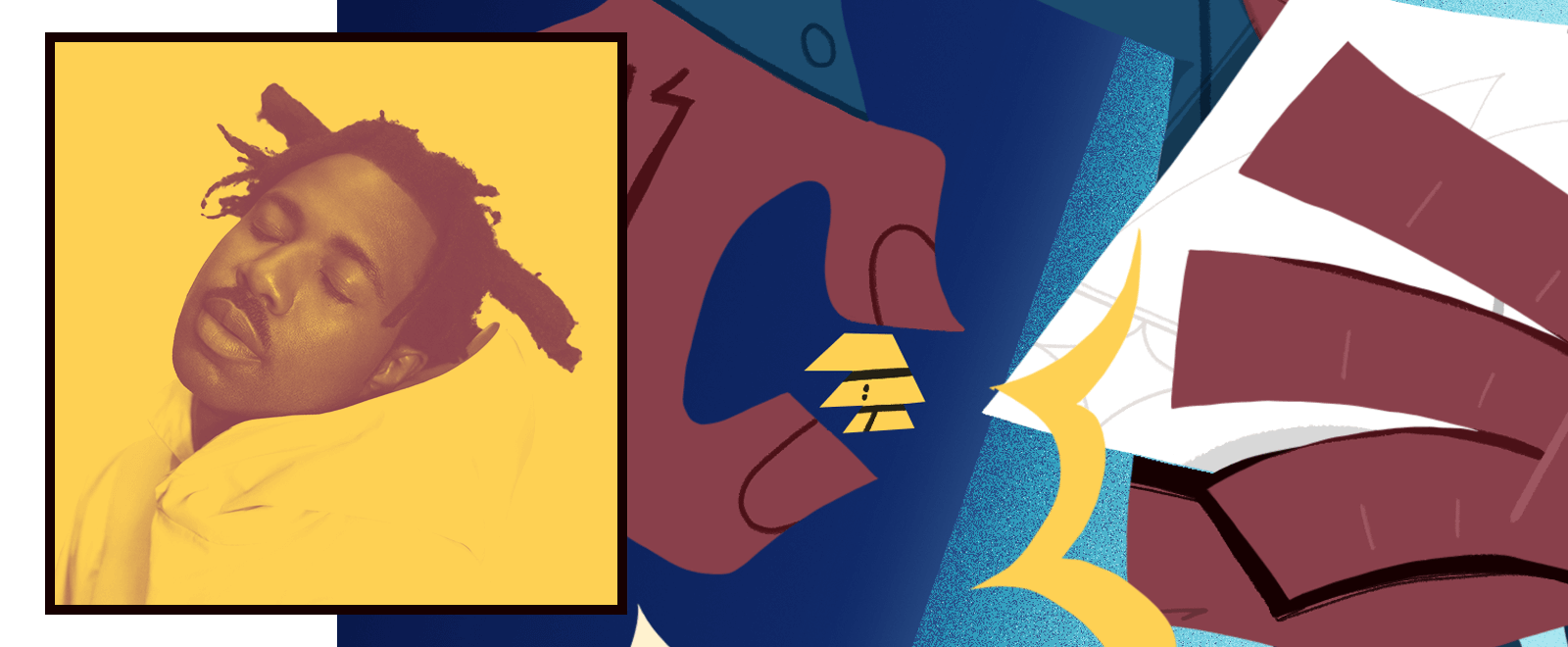

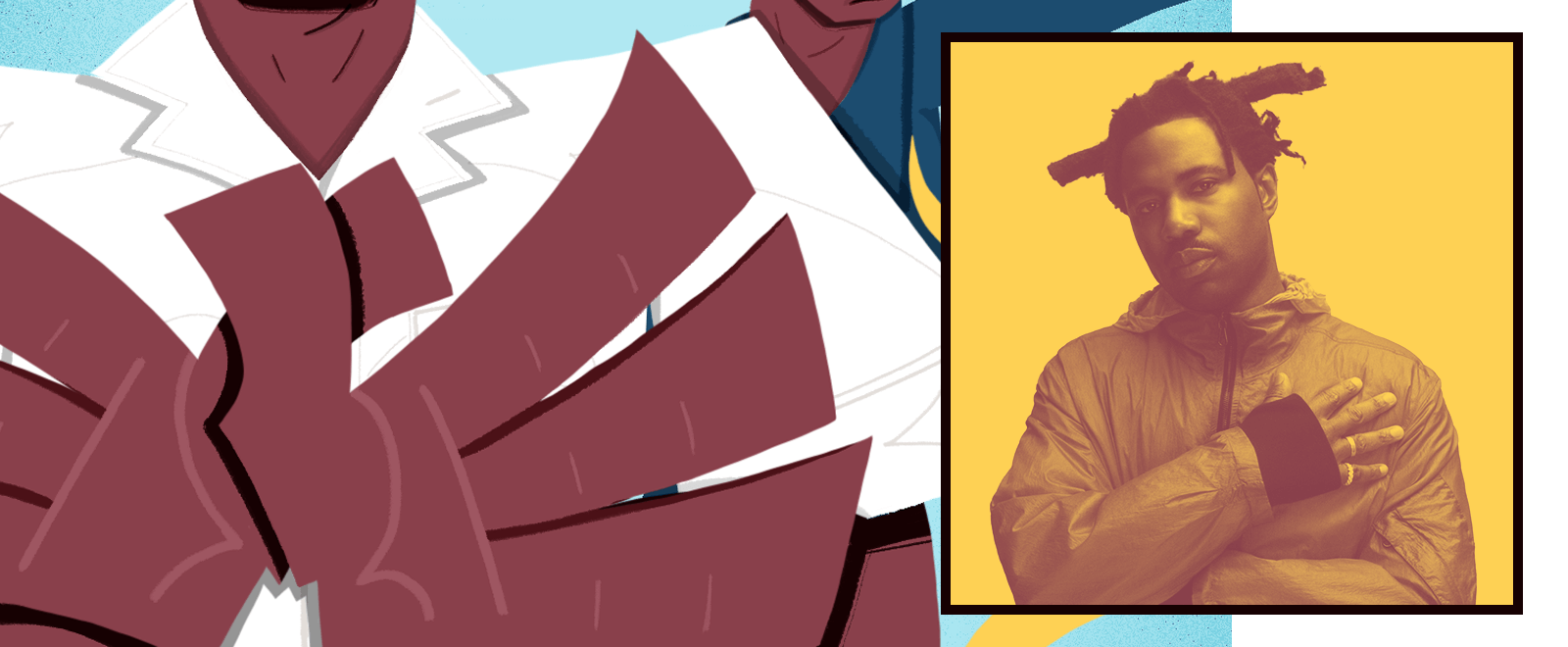

In today’s fast-moving musical climate driven by small soundbites, viral trends, and low attention spans, there aren’t many artists taking up space in the mainstream who can disappear for the better part of a decade and still have their fans waiting patiently on their every move. Some of the first that come to mind are heady, influential, and genre-shifting artists who focus on big-picture themes, like Frank Ocean or Beyonce. Not only can you add London-based electro-soul pioneer Sampha to that list, but both Frank and Bey saw something in him, enough to reach out for collabs long before he was a household name.

Linking up as well with other culturally defining acts like Kanye West, Kendrick Lamar, and Drake, who first attracted widespread attention to Sampha’s name 10 years ago on Nothing Was the Same track “Too Much,” Sampha has become a bit of a go-to collaborator on major projects when there’s need for a striking, emotive voice to take a song with vulnerable subject matter to the next level. Of course, it’s doubly effective when Sampha sings about his own life.

After taking home the Mercury Prize six years ago with Process, an album where a grief-stricken Sampha reckoned with cancer taking his mother’s life after it did the same to his father when Sampha was only nine years old, he has returned with LAHAI – another family-driven album where he expands his focus to the human condition at large.

Picking up a bit of a reputation as a mysterious, elusive figure due to his release schedule, Sampha will tell you that he does partially appreciate the perception that it’s given him – but not for the reasons that you might expect. Unlike some of those collaborators, Sampha isn’t driven by ego, but by humility; although a touch of Ocean-esque perfectionism certainly lingers around. Sampha is thoughtful, soft-spoken, and extremely deliberate with every word, and his desire to express himself in exactly the way he means crosses over to his musical output.

“I think it can be nice in that when I’m looking for inspiration or making a schedule, I have my space, when I don’t necessarily want to talk about things that I’m going through, or I feel really uncomfortable with,” he says. “I just want to be recognized for my work. It’s not like I ride or die on having that reputation. The bottom line is, if you’re talking to me, I’ll demystify that mystery really quick.”

It’s no mystery that most of the excitement for new Sampha music comes from the scores of people who have connected deeply with his voice; a wounded, yearning and vulnerable lilt that’s just as affecting in his baritone range or a falsetto. If it sounds like Sampha has a permanent lump in his throat – even when he’s singing about happier things – it’s because he does: After his family’s history of illness, one lyric on Process found him terrified of discovering a growth in his throat. It was tested multiple times, but doctors seemed to agree that while the cause is unsure, it’s benign.

Sampha now believes that it might be globus pharyngeus, a more psychological condition that makes it feel like a lump is there due to high levels of anxiety. For Sampha, music functions as an outlet for voicing those anxieties, serving as a snapshot of whatever big ideas are on his mind when a full project finally materializes. For whatever reason, one of the things on his mind this time around was the classic children’s book Jonathan Livingston Seagull, which his older brother read to him at a young age.

“I don’t remember much about the book in detail, I was six or seven, but some aspects of the story, like the seagull who wanted to practice flying for the sake of flying, not necessarily trying to attain a goal, there were certain things that spoke to me a bit,” he says. “There was also a synergy between some of the aspects I was thinking about, with finding community or feeling like you’re slightly outcast from a community, whether that be my cultural upbringing, finding you’re struggling with where home is, or music being a place to feel one with, or at home with.”

LAHAI ends with an image of Sampha at a family gathering, laughing and taking pictures. The narrative of the album has quite a few recurring themes, but the changes in Sampha’s life since the release of Process seem twofold. The first is a search for connection: if Process found a grieving man alone at a piano, LAHAI feels like a slight backtracking after realizing that support from others was what he needed most. The second is the birth of his first child, a daughter, in 2020. It found him admiring characteristics of his mother that sprung up once again, his mind spiralling through thoughts of cycles, reincarnation, and even the possibility of time travel. A powerful song on his latest, “Can’t Go Back,” finds him repeating his own live-in-the-moment mantra: “Can’t go back, but you can move forward slower.”

“I was watching this documentary with Brian Cox about entropy. He was saying that it’s very difficult for time to go backwards, it’s nearly impossible. If someone really wanted to make a time machine, they couldn’t. It got me thinking about how I’ve wanted to go back,” he says. “I’m also constantly preoccupied with looking towards the future, feeling like I never really have the time to do songs or to appreciate a moment. I’m distracted by a phone or something. I’m now just trying to become more aware, like ‘Oh, I never noticed that sign before.’ It’s kind of like mundane poetry.”

While it’s also his own middle name, Sampha’s decision to title the album LAHAI – the name of his late grandfather – came partway through the process as he started to write more and more lyrics about coming to terms with accepting the events of the past. After all, elements of it still persist in the present. Whether it’s a departed family member whose lessons remain or a tough decision that turned out to be a blessing in disguise, the project finds Sampha delivering its thesis statements on the spacey, half-rapped “Satellite Business”: “Thinking maybe there’s no ends, maybe just infinity, maybe no beginnings, maybe just bridges” or “Through the eyes of my child, I can see you in my vision.”

“I never met my grandpa, but this is the album where I was thinking about intergenerational connections, looking forward and recognizing people who are no longer here,” he says. “It felt like a fitting name for the record, because I was thinking about those close to me.”

The themes surrounding birds don’t only show up on tracks like “Jonathan L. Seagull.” There’s another one titled “Inclination Compass (Tenderness),” after the scientific phenomenon giving migrating birds the innate ability to know exactly where they’re meant to fly – even if they’ve never been there before. It’s something that Sampha applied to stepping back from it all, letting go of overthinking what you can’t change, and letting life steer you where you’re meant to go.

“The bird’s eye view is something I felt like I needed at a certain point in my life, where you feel like you’re sleepwalking towards a cliff, numb to your past and your future. You can’t locate your place in space and time, or how you got to where you are. It can become so complicated that you can get slightly desensitized,” he says. “Birds and butterflies use their compass, which for me sometimes is like recognizing that you’re not in full control, and things are the way they are. Like how you have to run or do strength training to keep healthy. I didn’t design that, it’s just the way it is. There’s a certain element of submitting to that.”

Since so much of LAHAI touches on family, it makes sense that its sound also finds Sampha looking towards his roots. The youngest – by a large margin – of five brothers, Sampha’s familial origins are in the African nation of Sierra Leone. After his parents moved to the United Kingdom in the 1980s, Sampha’s first introductions to music were as a toddler, watching his teenaged brothers experiment in a makeshift home studio they built. West African folk music was often around, and LAHAI finds Sampha building out his electro-soul sound with touches of Wassoulou.

“If I was to take the modular synth tones out on [lead single] ‘Spirit 2.0,’ the actual rhythm is not too dissimilar to Wassoulou music: repetitive syncopation, polyrhythms and simpler parts,” he says. “People talk about certain types of African music being more like architecture. You have a base rhythm, and instead of it changing, you continue to build on top of it. Something that’s kind of dense, but also kind of minimal. There’s a constant groove.”

All in all, Sampha says that his biggest artistic evolution since Process is gaining more confidence to work with others, presenting the ideas in his head to collaborators. If you take a look at some of his past interviews, Sampha often described his ability to sink into the background and simply be of service to someone else’s vision as “little brother syndrome”: the quiet one always asked to help out without any questions. In fact, in his earliest days, Sampha didn’t even want to use the voice that has touched the souls of so many – he saw himself as more of a producer, but like the birds following their inclination compass, his abilities were special enough that became evident that it was something that he needed to do.

“Maybe I’m a little more settled, or a little more confident in some ways, but in a lot of ways I’m still the same,” he says. “It feels like this is just another snapshot of my life and my ideas – or a particular section of things I was going through.”

Although the snapshot of his debut was the kind of image that might bring tears to your eyes, this time around, things seem to be looking up. Sampha is the kind of guy who takes the time to sift through the mundane, and his newfound appreciation of it all allows him to touch on something truly powerful. Next time he touches down, he’ll certainly let us know how he’s feeling. But for now, let him be.

By Cam Delisle

In the wake of her breakthrough third album, Through The Wall, the experimental-R&B auteur reflects on a career-defining year.

By John Divney

Still processing their debut album, Vancouver’s latest art-rock unit proves collaboration is the new rebellion.

By Cam Delisle

The elusive Kevin Parker soundtracks the self-medicated search for bliss on his fifth album, Deadbeat.