By Cam Delisle

Between the virality of “Love Me Not” and the clarity of her sophomore LP, the Chicago-born soul innovator proves that real pop music takes time.

I got the invite to appear as an extra in a new music video by Snotty Nose Rez Kids the night before. Finishing work early, I raided my closet for any semblance of 80s punk clothes and made my way through Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside to the Rickshaw Theatre, entering through the back alley. It was my first time inside a music venue in two years and there was a palpable buzz of anxiety and anticipation. I hadn’t heard the song — a yet-to-be released SNRK track that you’ll just have to wait to see and hear — but I knew it would be a banger. With everyone in their places, they called us toward the stage and we were told to get ready to mosh. The song came on over the PA and we all went crazy. I was bleeding from my face by the second take — I felt alive again.

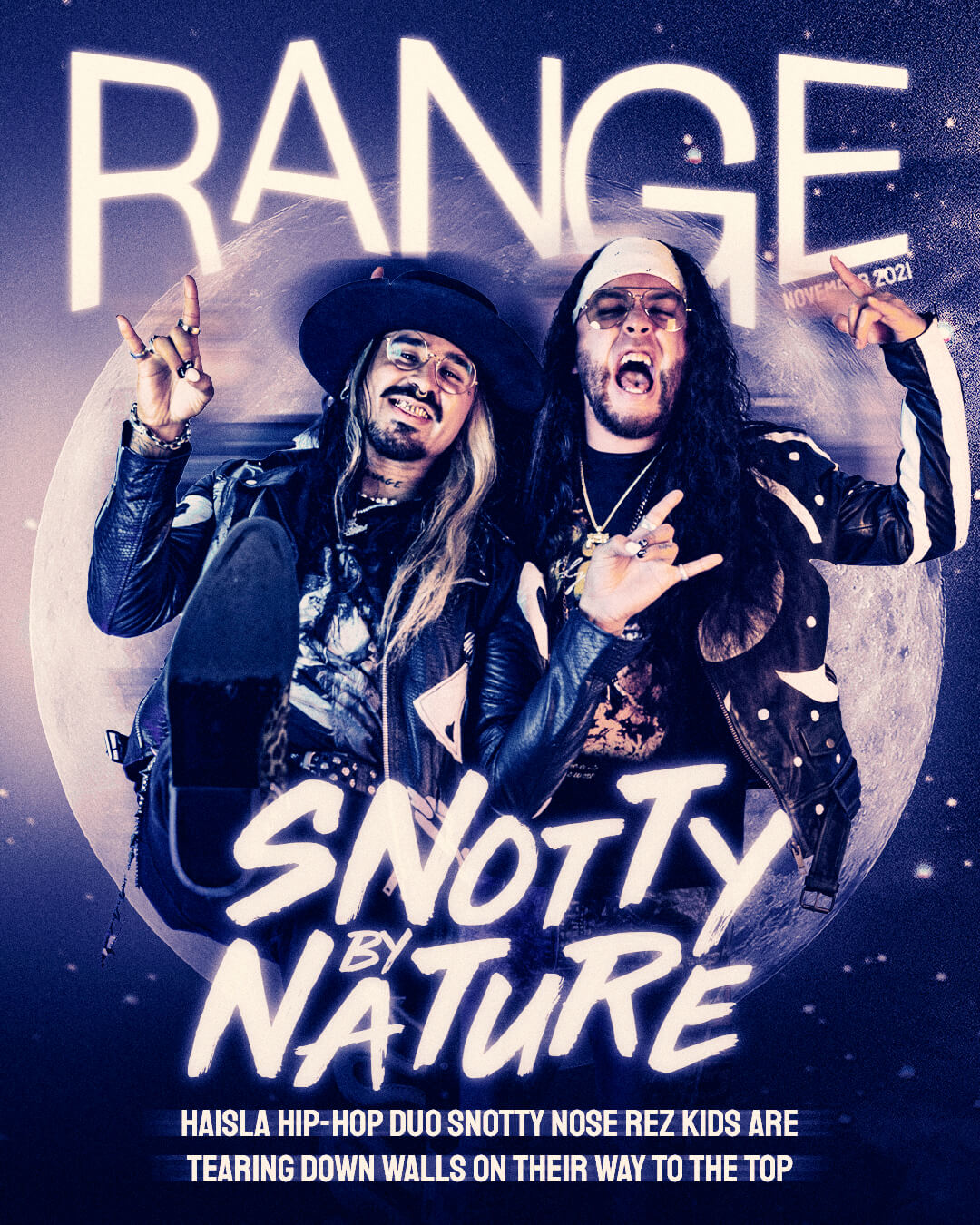

But more importantly, I felt like I was a part of something again. A community. This is what Darren “Young D” Metz and Quinton “Yung Trybez” Nyce excel at. The Haisla hip-hop duo make you feel welcome and important with an energy that is infectious yet balanced. Young D is the Yin to Yung Trybez’ yang. They complement each other perfectly, not just in personality but lyrically, and even spiritually. Talking to them a couple weeks after the shoot, I get the sense they aren’t just making music but rather cultivating an entire movement.

“As Darren (Young D) always says, ‘we want to make history.’ We want to pave the way for the people coming up behind us. The way we look at ourselves is, we’re just two Indigenous men and we can only speak from our own context,” says Nyce one evening over a couple beers at my apartment where I have invited the duo over to discuss their new album, Life After, just one week before its official release. He continues: “We understand our privilege and we understand that a lot of people don’t get the opportunities we get, but a lot of that was worked for. We did put in the work.” From hawking their CDs at the All Native Basketball Tournament to being on the frontlines of Indigenous resistance and touring the world, Metz and Nyce are cultivating a community.

Of course, like many, this momentum came to an abrupt halt with the global pandemic. For a group that played 100+ shows after the release of their critically acclaimed sophomore album, Trapline, this was a huge blow. And while their latest, Life After, deals with the isolation that came from life in lockdown — as well as issues of substance use, addiction, depression, family struggles, and racism — it also suggests hope for the future. At least part of this optimistic outlook can be attributed to Indigenous culture.

“As Indigenous people who have been shit on year after year after year by the government, from the people, from our own people, the media, the police… I feel like Indigenous people have developed our own sense of humour that only we get,” Nyce says. “For us, the way we grew up listening to rap and hip-hop, it was so dark and heavy and it just weighed on you. You couldn’t listen to it more than once unless you were in the right mindset. So for us, coming up, our message, our music, we wanted to talk about the heavy stuff but with a positive spin. And making sure that at the end of the day you left smiling — on a high note. We never want people to feel down on themselves. We want to lift our people up, not bring them down.” Metz chimes in: “It’s just like our name also, Snotty Nose Rez Kids; it explains who we are without having to explain who we are. You gotta have a sense of humour when you come through trauma.”

That irreverent Indigenous sense of humour is all over Life After. There’s also a lot more sonic experimentation, something the duo accredits to the time and space afforded by the pandemic. “The singles on this album, not one of them sound the same,” says Metz. “They all sound different. A lot of experimentation went into this project as a whole and a lot of that came down to us just having time to sit back and chill with the homies and make music the way it’s supposed to be done.”

The result is a sonic tapestry woven together with narrative flair and vibrant imagery. At times the beats are sparse and roomy. At others, Metz and Nyce are in full-on warrior mode, spitting venom at everything from the police to the church to the government, but always with their signature snark. Lyrics like “Spazzing out like Kanye, just imagine me on a bad day. Pullin up to the blockade with a latté, I’m boujee” encapsulate their approach to tough subjects with a sarcastic yet introspective lens.

Of course, storytelling is a fundamental aspect of Indigenous culture and SNRK does it well, both on record and in a live setting. They compare their live show to a good comedian, who should have a thread that ties everything together. Indeed, their performances are wrought with tension, a dynamic push and pull between each rapper, the audience, and the music — peaks and valleys, yin and yang. Metz expands: “People don’t understand how much goes into live shows. We pride ourselves on our live shows. For us, that’s where we win fans. You can hear us on wax, and they’re like, “yeah this is a’ight” but they’re not truly listening. When we’re live we can see them and look them in the fucking eye and be like ‘this is me.’” “Although sometimes you look the wrong person in the eye and forget your lyrics,” Nyce adds with a flash of his grills.

Although my own touch points on hip-hop are woefully inadequate, the pair both light up when I mention Maestro Fresh Wes, whom I grew up listening to. “Maestro came up to us and asked us for a picture bro! He waited for us after our show with the Sorority in Toronto. He dapped us up and was like, ‘Boys, I just want to say congrats on the year you’re having.’ That meant the world to us. Then he said ‘Make history, not records.’”

And that’s what they’ve done. Metz and Nyce recount how their debut full-length, Average Savage, was made with a shitty Shure 57 microphone in a bathroom in Nyce’s apartment, which was then shortlisted for the Polaris Prize and nominated for a Juno Award. With a team suddenly behind them, they made Trapline, which again was shortlisted for the Polaris. They talk with pride that they did it all as independent artists on their own label. “That’s another thing we’ve always wanted to do is make our own empire, for lack of a better word,” says Metz. “You know, we’re just two kids from the rez man. We’re from a small town. People say they’re from a small town and they’re like, ‘yeah I’m from Nanaimo or Port Alberni or whatever.’ No we’re from a small town bro, Our rez is under a thousand people. The town itself (Kitimat) is under 10,000. To be able to go from there and start our own record label and call our own shots; we just wanna show the youth—not just indigenous youth but youth all over—’yo, you could do this.’”

It’s an inspiring career arc to be sure. And it’s one that Metz reaffirms with one last story. When he was four years old, while walking back to the reservation one night with his baba, he looked at the lights at the Alcan factory and said, “It’s a big world out there; across the harbour is New York City.” And now look at them. New York City is just another tour stop on the way to world domination.

Photo by Darrole Palmer / Design by Alex Kidd

By Cam Delisle

Between the virality of “Love Me Not” and the clarity of her sophomore LP, the Chicago-born soul innovator proves that real pop music takes time.

By Gregory Adams

The legendary indie rocker traces the lines from Pavement to Pavements.

By Ben Boddez

The famously riotous rapper’s new project, LETHAL, comes after a year of reckoning with her real self.