Featuring Cindy Lee, Nemahsis, Wyatt C. Louis, and more — These Canadian artists all commandeered our headphones this year in a compelling way.

The Bobby Tenderloin Universe Rides Again

With new album Satan is a Woman, the Edmonton-based outlaw country act bring their classic prairie sound to a new cosmic frontier.

by Neil Jefferies

Photo by Heather Saitz

- Published on

Paul Arnusch — the Edmontonian frontman for the Bobby Tenderloin Universe — first learned to play the piano next to his grandma. She was a ragtime pianist in the ’20s and ’30s, a woman who endured many difficulties in her own life and wore them with a heart covered sleeve, and he was just a boy.

“My grandma was always a ray of sunshine, despite facing many emotional challenges in her life. She outlived four of her five children, my mother included, and her first husband, whom she adored, passed away young—on the very day I was born,” Arnusch tells RANGE. “I believe this is why she carried a unique depth of joy that could brighten any situation. When she moved in with us to help out while my mom was ill, we would sit side-by-side at the piano in our home, an old wooden work of art that produced a beautifully imperfect sound.”

While his grandfather, a pastor named Sigmund, ascended gracefully into the heavens, Arnusch must have crossed paths with him because he inherited his same uplifting spirit. Eventually Arnusch would find his place next to his grandmother at the piano and it was here where his love of music was formed.

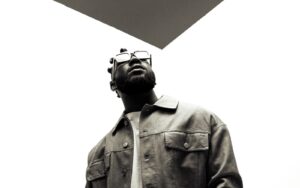

Paul Arnusch. Photo by Christan Masylyk

Arnusch has played in bands for his entire life — The Whitsundays, Faunts, and The Floor, just to name a few — but it was about six years ago that he started the Bobby Tenderloin Universe; a nitty gritty psychedelic country band with just enough polish to make their stories shine.

Coming out of the bull pen strong, when Arnusch assembled players for the first iteration of the band, they performed their first show in front of a fella by the name of Orville Peck who was standing in the crowd, enjoying what he was hearing. “Next thing we knew, we were galavanting around the US with him, right as he was on his rise to the stratosphere.”

In those early days, the BTU toured as an eight-piece. And while they enjoyed each other’s company and partied hard wherever they went, they eventually pared down their constellation of players to a quartet.

BTU is a band that balances the past and the future on a blade, or rather, a band that ignores time all together. They lean their outlaw frames on a crooked fencepost and wear their prairie heritage proudly like a well-hung bolo tie. Yet despite their connections to the past and obvious admiration for Lee Hazlewood and Johnny Cash, the band is without a doubt modernized, with elements of Arnusch’s songwriting bringing to mind the likes of David Berman (Silver Jews) or Bill Callahan. It’s quick to the punch, wise, witty, honest and rooted in storytelling. He is just as likely to dangle ambiguity in your face as he is to kick you in the chest with a simple lyric about loneliness, love, and good ol’ fashioned sinning.

“Most of it comes together as I’m going about my day,” Arnusch says. “The next step is to play the song idea on both piano and guitar, which can inspire different ideas. Finally, once I feel the song is done, I go into my basement, where I record it on the instruments I have and can play. Then I send it to Nathan (Gray), who records pedal steel and sometimes dobro, which adds the icing to the cake.”

The band’s new album, Satan is a Woman, is a revitalizing take on outlaw country; it’s janky and imperfect, much like the piano Arnusch grew up playing on. The songs range from playful and joyous to lonely and desolate. It’s a 10-track boot-stompin’ body of tricks, rooted deeply in the prairies but with eyes into the cosmic. It’s filled with comical social commentary in the modern age (“I Will Unfollow You,”) tales of heartbreak (“When the Bullet Hits the Bull,”) and waltzing, whimsical, yearnings (“Marigold.”)

“I strive to create music that serves the lyrics, so I approach it more like painting than just playing or recording. When I record, I prefer to move quickly without worrying too much about perfection; it often feels transcendent,” Arnusch says. “Perhaps the universe I tap into during that creative state is different enough from ours that it gives the songs a ‘cosmic’ quality. But I don’t consciously try to achieve that—I write country songs, and they just come out that way.”

By Stephan Boissonneault

The Montreal garage punk act pairs a bizarre real-life memory with vibrant animation from digital artist Arturo Baston.

By Stephan Boissonneault

Inside the Montreal-based songwriter's creative space where fashion and music collide - with our friends at Brixton.